Anne Jacobson

Oak Park, Illinois, United States

Portrait of Thomas Sydenham, Mary Beale, 1688 |

Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689) is known as “The English Hippocrates” because of his detailed physical examinations, painstaking record keeping, and attention to the treatment of illness.1 At a time when the medical profession espoused theory and systemization, his belief in the power of observation and primary experience over scientific theory drew criticism from many of his contemporaries. His formal medical education was limited and interrupted by periods of military service and illness, which may have also cost him traditional accolades. Skeptical of studies in the natural sciences, he instead preferred the works of Hippocrates, Cicero, and Bacon, and even recommended Cervantes’ Don Quixote as a means to learn medicine. Other scientists of his age such as John Locke, Robert Boyle, and Herman Boerhaave admired and shared his empirical approach.2 Through his meticulous work, Sydenham was the first to describe scarlet fever; identify the link between fleas and typhus; popularize the use of quinine to treat malaria; explain a movement disorder that occurred after fever (now known as Sydenham’s chorea); and introduce a liquid tincture of opium for pain relief. His opus of recorded observations, Observationes Medical, would serve as a functional textbook for the next two hundred years.1

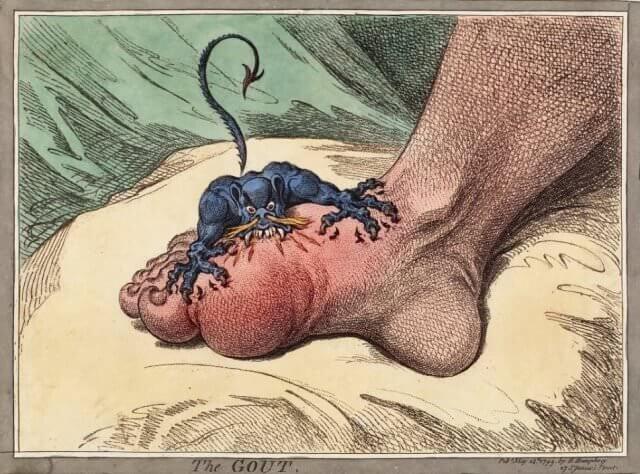

Sydenham’s most famous and enduring work was his 1683 treatise on gout , which took the art of clinical observation to a personal level. Having suffered from frequent and debilitating attacks of gout from the age of thirty, he gave a descriptive first-person account of the affliction:

The regular gout generally seizes in the following manner: it come on a sudden towards the close of January, or the beginning of February, giving scarce any sign of its approach, except that the patient has been afflicted, for some weeks before, with a bad digestion, crudities of the stomach, and much flatulency and heaviness, that gradually increase till the fit at length begins; which however is proceeded, for a few days, by a numbness of the thighs, and a sort of descent of flatulencies through the fleshy parts thereof, along with convulsive motions; in the day preceding the fit the appetite is sharp but preternatural. The patient goes to bed, and sleeps quietly, till about two in the morning, when he is awakened by a pain, which usually seizes the great toe, but sometimes the heel, the calf of the leg, or the ankle. The pain resembles that of a dislocated bone, and is attended with a sensation, as if water just warm were poured upon the membranes of the part affected; and these symptoms are immediately succeeded by a chillness, shivering, and a slight fever….3

He also described the physical and emotional comorbidities of gout, again incorporating his own experience:

Moreover the patient is likewise afflicted with several other symptoms; as a pain in the hemorrhoidal veins, nauseous eructations, not unlike the taste of the ailment last taken in, corrupting in the stomach, happening always after eating any thing of difficult digestion, or no more than is proper for a healthy person, together with a loss of appetite, and a debility of the whole body, for want of spirits, which renders his life melancholy and uncomfortable.3

The Gout, James Gillray, 1799 |

Sydenham differentiated causes and treatments for acute and chronic conditions. Gout was believed to be a chronic illness caused by a disturbance of bodily humors related to digestion. While Antoni van Leeuwenhoek was describing the appearance of gout crystals in his pioneering microscopy work in 1679,4 Sydenham eschewed anatomic pathology and microscopy on religious grounds.5 He prescribed bleeding, sweating, or purging for acute illness, but recommended temperance and rebalancing the humors for chronic conditions. In the case of gout, he believed that drawing the offending humors back into the digestive tract was more dangerous than the gouty attack itself, and relied on dietary alterations and pain management for treatment. His introduction of laudanum (opium tincture) into clinical practice likely originated for this purpose. While Sydenham correctly identified obesity and excessive intake of red meat and alcohol as risk factors for gout, his Puritan religion also likely influenced his recommendation for temperance rather than other treatments. Ironically, colchicine, an ancient natural remedy and future pharmacologic treatment for acute gout, was not used in England for over one hundred years due to Sydenham’s influential opposition.4

Sydenham reiterated and reinforced the adage that gout, being an affliction of the wealthy upper class, was preferable to the common and more deadly diseases of the lower classes such as tuberculosis and plague. He wrote:

But what is a consolation to me, and may be so to other gouty persons of small fortunes and slender abilities, is, that kings, princes, generals, admirals, philosophers, and several other great men, have thus lived and died. In short, it may, in a more especial manner, be affirmed of this disease, that it destroys more rich than poor persons, and more wise men than fools; which seems to demonstrate the justice and strict impartiality of Providence, who abundantly supplies those that want some of the conveniences of life, with other advances, and tempers its profusion to others with equal mixture of evil; so that it appears to be universally and absolutely decreed, that no man shall enjoy unmixed happiness or misery, but experience both: and this mixture of good and evil so adapted to our weakness and perishable condition, is perhaps admirably suited to the present state.3

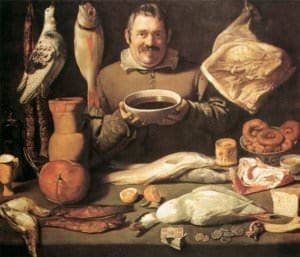

Gout was, in fact, thought to be a desirable affliction in some respects, since it identified members of the upper classes and was even believed to be protective against other more deadly diseases.6 These beliefs served not only to relieve the physical and emotional suffering of gout by means of a social trade off, but upheld the norms of diet and lifestyle for the upper class. An attack of gout was a circular but acceptable argument for the maintenance of a sedentary lifestyle. Obesity and excessive intake of red meat, shellfish, sugar, and alcohol are known risk factors for gout. A man of Sydenham’s social stature would have eaten a typical upper class diet, consisting of meat served as much as three times a day; cakes, breads, and pies made with copious amounts of butter and sugar; and large amounts of wine, beer, and ale, which were thought to be safer to drink than water.7 A sample recipe from the time period for black pudding reads like a warning label for a gouty attack:

Kitchen Scene, anonymous 17th century artist (Spain), 1610 – 1625. |

Take a quart of Sheeps-blood, and a quart of Cream, ten Eggs, the yolks and the whites beaten together; stir all this Liquor very well, then thicken it with grated bread, and Oat-meal finely beaten, of each a like quantity, Beef-suet finely shred, and Marrow in little lumps, season it with a little Nutmeg, Cloves, and Mace mingled with Salt, a little sweet Marjoram, Thyme, and Penny-royal shred very well together, and mingle them with the other things, some put in a few Currans: Then fill them in cleansed Guts, and boyl them very carefully.8

In modern medicine, gout has a known association with coronary artery disease9, kidney stones 10, and sleep apnea.11 Sydenham is known to have had bouts of clinical hematuria and gout, and his death in 1689 is thought to have been related to both. Given what is now known about the comorbidities of gout and its relationship to diet and sedentary lifestyle, it is very possible that he also suffered from metabolic disturbances that affected his heart, lung, and kidneys. He suffered and died in elite company. Other famous historical figures known to have endured gout include Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander the Great, Charlemagne, Leonardo da Vinci, John Milton, Charles Darwin, Carl Linnaeus, and Isaac Newton. William Osler, the American physician who famously espoused the importance of the “care of the patient” two hundred years after Sydenham, also suffered from gout.12 Perhaps it is difficult for physicians and learned people, even when they include themselves in their own observations as Sydenham did, to moderate disease in themselves, even when the risk factors are well understood and partially under their own control. As Benjamin Franklin, another member of this elite group that suffered from “the disease of kings” once said, “Wise men don’t need advice. Fools won’t take it.” It is unknown how well Thomas Sydenham, both medical expert and gout sufferer, took his own advice. However, his honest and detailed descriptions of this and many other conditions were a significant step forward in the science of modern clinical observation.

Notes

- Encyclopedia Britannica. “Thomas Sydenham.” https://www.britannica.com/biography/Thomas-Sydenham.

- Whonamedit? – A dictionary of medical eponyms. http://www.whonamedit.com/doctor.cfm/1989.html.

- Sydenham, Thomas. “A Treatise of the Gout and Dropsy.” 1783. Google Books.

- Nuki, George and Simkin, Peter. “A concise history of gout and hyperuricemia and their treatment. Arthritis Research and Therapy, 2006, 8(Suppl 1):S1.

- http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/broughttolife/people/thomassydenham

- Scholtens, Martina. “The glorification of gout in 16th-to-18th-century literature.” CMAJ. 2008 Oct 7; 179(8): 804-805.

- http://cookit.e2bn.org/historycookbook/33-341-stuarts-Food-facts.html

- http://www.godecookery.com/engrec/engrec137.html

- Pagidipati NJ et al. “An examination of the relationship between serum uric acid level, a clinical history of gout, and cardiovascular outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndrome. AM Heart J. 2017 May; 187:53-61

- Landgren AJ et al. “Incidence of and risk factors for nephrolithiasis in patients with gout and the general population, a cohort study.” Arthritis Res There. 2017 Jul 24; 19(1):173

- Zhang Y, Peloquin CE, Dubreuil M, et al. “Sleep Apnea and the Risk of Incident Gout : A Population-Based, Body Mass Index-Matched Cohort Study.” Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015; 67:3298-3302

- C. Ronald MacKenzie, “Gout and Hyperuricemia: an Historical Perspective. Current Treatment Options in Rheumatology (2015) 1:119-130.

ANNE JACOBSON, MD, MPH, is a family physician and writer. Her work has been published in the anthology At the End of Life: True Stories About How We Die, the Journal of the American Medical Association, The Examined Life Journal, Hektoen International, and Hofstra Windmill. She is an associate editor at Hektoen International and lives in Oak Park, Illinois.

Fall 2017 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply