Jeffrey Levine

New York, New York, United States

I stared at the blank surface of my drawing pad, confused and frozen in fear. It was slightly larger than a sheet of typing paper but looked like it spread from horizon to horizon. The naked model sat leisurely, unashamed, her eyes fixed on a distant, imaginary cloud formation. My hand trembled as I clumsily uncapped my pen and began to make unsure black marks that made no sense. The room was quiet except for the swish of pencils, brushes, and charcoal sticks. It was the Friday night sketch class at the Art Students League, and this was my first time back in nearly three decades.

My dad died in June, and the summer was long and colored by grief. As a child I wanted to be an artist but he would have none of it. Growing up in a rough neighborhood in Jersey City I knew that the best way out was a solid profession like medicine. I never lost interest in making art, and in high school while others were buying drugs I spent my money on drawing tools—keeping sketchbooks with dip pens and india ink. Forget about easels, watercolors, and cameras as the cost was prohibitive. I promised myself that I would support the pursuit of art with a career as a doctor, and insulate my creativity from the pressures of commercialism and economics.

In college my pre-medical curriculum was grueling and allowed little time for art, but I still kept sketchbooks. I moved back to Jersey for medical school and was thrilled to have access to the neighboring world of New York City where I discovered the Friday night sketch class at the Art Students League. For two dollars I could immerse myself in drawing the human figure, unhindered by pressure to get passing grades. After graduation my internship started, and with my first paycheck I drove into the City and bought a drafting table and paints. By the end of my residency I built a painting studio in my apartment in a run-down neighborhood on the outskirts of Newark.

Medical school sketchbook, 1977

Medical school sketchbook, 1978

I moved into Manhattan to specialize in geriatrics, and my tiny living space required downsizing the scale of my art. My sketchbooks and paints went into storage and much of my studio was given away or discarded. I always wanted to take pictures, and to my delight the International Center for Photography was only a few blocks from the hospital. I took evening courses, bought used equipment, and built a darkroom in my already cramped apartment. While completing my fellowship, I photographed the streets of Manhattan at dawn and developed the film at night. Rust from the pipes in my walk-up brownstone always left spots on the negatives. Eventually I found ways to integrate photography into my work as a physician. I also stopped drawing.

Photography was an easy medium to adapt to medicine. I discovered an interest in wound care because it enabled me to take pictures in the workplace. In nursing homes there were plenty of pressure ulcers and other skin conditions to photograph. The camera records a wealth of information quickly and includes every detail of whatever it is pointed at, in contrast to drawing where the elements are suggested at a leisurely pace with well placed line and tone. When photographing, there is the reassuring feel of a precision instrument in your hand, and the process is more technologically complex than the fluid, direct, and intuitive approach with pen or pencil. It is not that there is less art to photography; it just entails a different type of craftsmanship.

I have since published my wound photos in journals and books, and used them in numerous lectures, but I doubt anyone appreciates these as art. I certainly use elements of composition and balance creating images useful for teaching students and colleagues, but rendering subjects such as infected pressure ulcers aesthetically pleasing for a broader audience is not on the map. Perceptual skills central to drawing such as understanding edges, spaces, and perspective are not necessary for creating technical pictures of wounds.

Years passed and I got married. My wife helped nurture my artistic pursuits. I expanded my repertoire and started photographing older people in the community to document the aging process, a project that dovetailed with my day job as a geriatrician. When digital technology made film obsolete, I bought new equipment and taught myself image processing technologies. Then my dad’s health started to go downhill. As a geriatrician I knew well the signals and transitions leading to what would follow, having been through the scenario numerous times with my patients. My medical knowledge, however, did not lessen the pain.

Some weeks after his death I decided to clean out some storage, and underneath a pile of boxes was the fishing tackle box that held my drawing supplies. I opened it up and found a time capsule that included a ticket to a Friday night sketch class dated 1983. A lifetime had passed since I last went there.

There I was in 2012, in a sketch class at the Art Students League, sweating nervously in front of a blank sheet of paper. The seconds ticked slowly as I applied misplaced analytic skills to my drawing, taking the figure apart and making literal interpretations of light and shadow. I fruitlessly imitated a camera that recorded detail with optical formulas to get aesthetic conclusions. My first attempts at drawing were a mess—a dismal array of black scratches that were far from pleasing. Rather than think abstractly to interpret what I saw, I used logic to fit the jumble of visual information onto the page.

Feeling challenged by the task at hand, I looked back at the drawings I had made decades earlier. Many were beautiful and full of emotion. Was my inability to reach this level the result of age, or were there elements missing in the process of creation? I needed to reopen channels of perception that had gone fallow. Only by harnessing portions of my right brain could I approach where I had been. The informal reality of line, shade, and color required not logic and analysis, but imagination and intuition.

In the 1960’s, Roger Sperry carried out studies revealing specialized functions of the cerebral hemispheres which earned him a Nobel Prize. He found that the left side of the brain is primarily analytic and verbal, whereas the right half takes care of space perception. The left brain is considered adept at logic, numbers, reasoning, and keeping track of time while the right brain is associated with intuition, creativity, and expressing emotions. The corpus callosum is the bridge composed of two hundred million axons that connects them, allowing exchange of information and integrating their function. In her classic book, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, Betty Edwards discusses the duality, or two-sidedness, of human nature and thought.1 These include divisions between thinking and feeling, intellect and intuition, objective analysis and subjective insight.

After several sessions with my sketch pad, I found myself continually drifting back to my analytic left brain comfort zone. My pictures were overworked and technical, and did not grab the moment in which they were made. The analysis of line placement caused a tempest in my head rendering my body tense and my drawings stiff. Waiting for a flash of inspiration was not an effective strategy, and I needed to loosen my muscles when handling a drawing pen. This meant making a space where I could explore in comfort the right side of my brain.

I converted part of my apartment into a zone for creative activity. I dedicated a bookshelf to resources that inspire, bought fresh supplies, and constructed a studio. The goal was to re-open my corpus callosum and employ intuition to the picture and substitute linearity with relationships and imagination. I began using a brush and colors to break old habits and expand my methods of seeing. At first, I felt like an awkward neophyte and made frequent excuses to avoid blank sheets of paper. I enjoyed neither the mental discomfort of being in a strange place, nor the muddy and inarticulate results.

I set aside time each day to make art. Gradually the messy shapes began to make sense, the lines became more fluid, and the process changed. During moments of drawing I felt a sense of calm where time did not exist, and I became one with the paper and materials. The cacophonous, distracting analytic struggle of where to place the pen was receding. I had begun to tap into the plasticity of the brain and briefly occupy my right hemisphere.

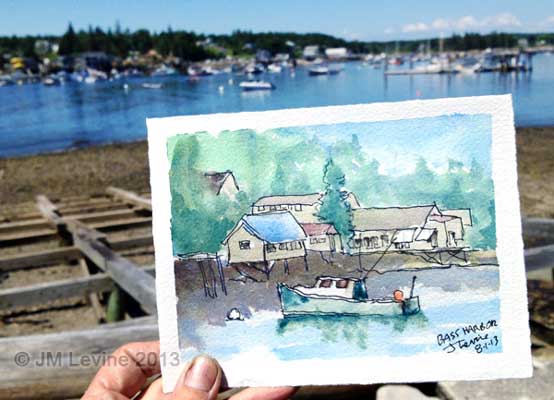

Maine sketchbook, 2013

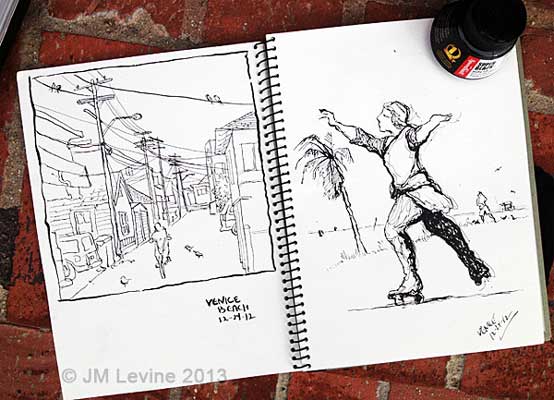

Venice Beach sketchbook, 2012

Small quick sketches of people on the streets of New York City were helpful. I observed the complex mechanics of how they walk, and the subtle nuances of posture and gait that render perceptions of youth, old age, and gender. Recognizing these characteristics and getting them on paper was a challenge that became easier with each try. My efforts at visual discovery made me aware of similar processes I employ in the clinic to examine patients and recognize the subtle faces of disease. Instead of drawing with a pencil to create a pleasing array of lines and shapes, I apply tools of technology along with intuition to confirm the diagnosis and offer a cure.

Medicine and drawing share basic skills of disciplined observation, and both tap directly into right brain function. Both are richly cerebral and engage processes verbal and nonverbal, detailed and holistic. Intuition plays a role in pursuing new lines of thinking, raising new questions and alternatives. The art of medicine is critical not only in diagnosis but also in decision-making, taking into consideration the needs, preferences, and culture of the patient and family. The art becomes essential in situations where choices become clouded in issues of ethics and end-of-life care. This is what attracted me to geriatrics, which I believe is the most humanistic of medical specialties.

Our culture creates a dividing line between science and the humanities, a line which permeates our educational system. A scion of this cultural divide is medical education, which is firmly grounded in science and technology and too often neglects the humanistic side of patient care. Most medical training emphasizes the left brain, utilizing logic and verbal skills along with the immense volume of information required to master the craft. This is important given the highly technological environment in which we work, but something is missing in the equation.

Healthcare is unique in that it bridges science and humanity, calling upon practitioners to be brilliant scientists as well as empathetic human beings. I believe that more emphasis on developing right brain skills through the arts will create better, more humanist attitudes. A humanistic approach to patient care requires opening the corpus callosum and allowing both hemispheres of the brain to collaborate on problem solving. This is sometimes not easy, particularly in the face of ingrained artificial dividing lines.

And so I continue the quest to improve my drawing, attending art classes, buying new sketchbooks, and filling them with images page by page.2 I look back on my journey to support my art through a medical career and the interesting places it took me. Even though I stopped drawing I was still making art and actively engaging my right hemisphere in the practice of medicine and pursuit of photography. In our world of high technology, complex billing codes, and electronic medical records it has never been more important to enrich our profession through the humanities. One cannot be an effective caregiver without the collaboration of both cerebral hemispheres.

Notes

1. Edwards B. Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. NY: Penguin, 2012.

2. For samples of Dr. Levine’s sketches see http://www.jmlevinemd.com/venice-beach-sketchbook-by-dr-jeff-levine.

This essay is copyright © JM Levine 2013 with all rights reserved.

JEFFREY M. LEVINE, MD, AGSF, is Attending Physician in the Department of Medicine, Division of Geriatrics, and Center for Advanced Wound Care at Beth Israel Medical Center, Petrie Division, in New York City. He is also Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. He has published articles on geriatrics, wound care, and medical history, and co-authored Pocket Guide to Pressure Ulcers. His images of human aging have appeared on over forty covers of The Gerontologist. He has a traveling exhibit Aging across America sponsored by the Global Alliance for Arts and Health and underwritten by the MetLife Foundation. His blog often features posts on growing old and the blending of medicine and art. Dr. Levine is also on the editorial board of Hektoen International.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Fall 2013 – Volume 5, Issue 4

Leave a Reply