Alex Ngo

New South Wales, Australia

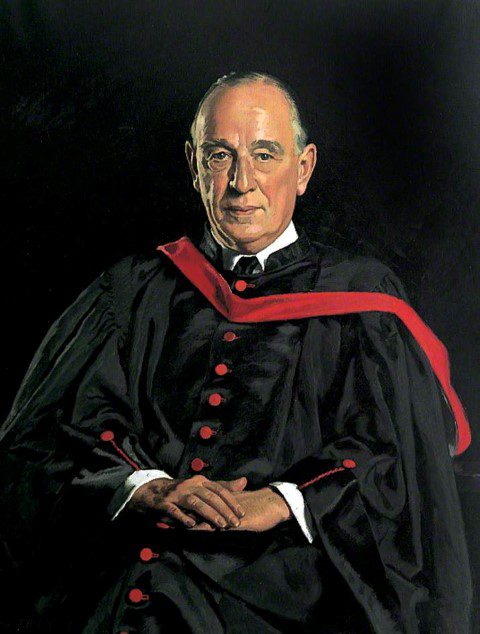

Edward Irvine Halliday, Institute of

Ophthalmology, United Kingdom

Sir William Stewart Duke-Elder (1898-1978) was one of the greatest ophthalmologists of the twentieth century. Unparalleled during his time, his contributions laid the foundations of modern ophthalmology.

Sir Stewart was born in Tealing, near Dundee, the son of a minister in the Free Church of Scotland. In 1915 he entered the University of St. Andrews as a foundation scholar and graduated in 1919 with a BSc in Physiology and a MA (Hons) in Natural Sciences. He completed his medical course at the Royal Infirmary, Dundee, and Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh, and graduated in 1923. He became a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of England the following year. He actively participated in university life, holding the position of President of the Students’ Union and enjoying rugby, cricket, and rough-track motorcycle racing.1, 2

In 1925 Sir Stewart earned an MD and a gold medal from St. Andrews for his dissertation on “Reaction of the eye to changes in osmotic pressure of the blood.” In 1927, aged 29, he earned a doctorate from St. Andrews for his thesis on “The nature of the intraocular fluids and the pressure equilibrium in the eye.” In 1928 he was appointed Honorary Consultant Ophthalmic Surgeon at St. George’s Hospital and the famous Moorfields Eye Hospital. In 1933 he was knighted for successfully operating on the British Prime Minister, Ramsey MacDonald. He became ophthalmologist to the Royal Family and remained in this position for 29 years, serving Edward VIII, George VI, and Elizabeth II.1, 2

Sir Stewart made many contributions to ophthalmology. Among his gifts to the world were his monumental seven-volume “Textbook of Ophthalmology” (1941-1954), of which he was the sole author, and his fifteen-volume “System of Ophthalmology“ (1958-1976). These were regarded as the ultimate compendia of ophthalmic knowledge in the past, and continue to be esteemed worldwide. His intellectual brilliance, command of the English language, clarity, and capacity to synthesize have captivated and enlightened many. Despite his demanding clinical practice, he contributed tirelessly to copious textbooks and scientific publications.1,2 Sharing glimpses of Sir Stewart’s life, longtime colleague and close friend Sir Stephen Miller revealed:

Stewart on two or three nights a week would begin writing at his desk after an evening meal, work through the night until six in the morning, sleep in his chair for an hour, then have a bath and a change of clothing, when he was ready to begin another day as chirpy and as lively as a cricket. I am convinced that he found his greatest happiness when on the stretch with his books around him.3

Sir Stewart served for many years as chairman of the editorial committee of the British Journal of Ophthalmology and Ophthalmic Literature. He created the Faculty of Ophthalmologists within the Royal College of Surgeons of England in 1945, and in 1948 he founded the Institute of Ophthalmology (now part of the University College London), of which he was Director of Research for 17 years. In 1954 he took charge of St. John Ophthalmic Hospital in Jerusalem. His contributions to medical literature earned him the title of Fellow of the Royal Society in 1960, a rarity for a clinician. During his time he received 16 medals and many awards. As president of numerous ophthalmological societies, he had powerful, international influence and frequently traveled abroad to deliver lectures.1,2

Sir Stewart was revered by his colleagues and admired by his patients, many of whom were referred to him from other continents. One glaucoma patient, whom he treated for more than 15 years, has recounted her first experience with him in surgery:

Sir Stewart came forward as I was wheeled into the operating theatre, bent over my tense person saying kindly, ‘I am here to hold your hand!’

And he did throughout the 30 minutes’ operation on the left eye.

At one point I spoke, ‘Will I be able to roll my eyes again?’

‘Indeed, yes!’ Sir Stewart, seated at my left side and holding my hand, replied. ‘At your husband and at Mr. Goldsmith [the operating surgeon]!’4

In 1965 Sir Stewart retired and the Institute presented him with a portrait of himself by Edward Halliday (see above), which hangs in the boardroom. He spent his final years battling emphysema but remained in close contact with his friends. Throughout his life, he had the love and support of his wonderful wife Phyllis.1

Sir Stewart was a dedicated pioneer in ophthalmology, leaving behind a legacy of excellence. To describe his achievements as phenomenal and extraordinary is no exaggeration. Sir Isaac Newton once stated, “If I have seen a little further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” Sir Stewart was indeed a giant, and it is upon his shoulders that we have been able to see great distances.

References

- Lyle, T. K., Miller, S. Ashton, N. H. 1980. “William Stewart Duke-Elder. 22 April 1898-27 March 1978.” Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society 26: 85-105.

- Scott, G. I. 1978. “Sir Stewart Duke-Elder, GCVO, MA, MD, PhD, FRCP, FRCS, FRS.” British Journal of Ophthalmology 62 (5): 344.

- Miller, S. 1995. “Glimpses of My Mentor, Sir Stewart Duke-Elder.” Survey of Ophthalmology 40 (1): 73-77.

- Smithford, K. S. 1987. “A Patient Remembers Sir Stewart Duke-Elder.” Survey of Ophthalmology 31 (4): 267-269.

ALEX NGO is a 6th year medical student (BMed MD; University of New South Wales, Australia), who feels grateful to be in the medical profession and is intrigued by the human eye. He has completed an ophthalmic research project and has completed an elective term at the Sydney Eye Hospital, Australia. He wishes to one day volunteer in eye care programs in developing countries.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Spring 2015 – Volume 7, Issue 2

Leave a Reply