James L. Franklin

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

|

Théophile Alajouanine (1890–1980) |

Théophile Alajouanine delivered the Harveian Lecture to the Harveian Society of London on March 17, 1948. It was published in the journal Brain in September 1948 and became a medical classic, most frequently cited in papers devoted to the neurology of musical creativity and to the illness of one of the leading composers of French classical music in the first half of the 20th century, Joseph-Maurice Ravel (1875–1937).1

Théophile Alajouanine was born in 1890 and lived until 1980. He was a pupil of Joseph Jules Dejerine (1849–1917) and worked with Georges Charles Guillain (1876–1961) and Charles Foix (1882–1927). He wrote prolifically on many topics but was especially interested in aphasia. His name is associated with the eponyms Foix-Alajouanine disease (a rare disease of the spinal cord characterized by dysfunction of the spinal cord due to a dural arteriovenous malformation) and with Marie-Foix-Alajouanine syndrome (ataxia of the cerebellum in advanced age, frequently due to alcohol abuse).

Alajouanine’s lecture sets out to examine the impact of aphasia on artistic realization in three branches of artistic endeavor: literature, music, and painting. Three famous artists, a writer, a musician, and a painter whom Alajouanine knew and on whom he consulted are discussed. He reviews their artistic productivity before and after the onset of their illness and draws conclusions about the impact of aphasia on artistic endeavor. At the time of his lecture, Alajouanine could not divulge the identity of the writer or of the painter: the composer was Maurice Ravel whom he examined for over a two-year period. Since the publication of this paper, the identity of the writer and the painter is now known to us, and many details of the tragic illness that robbed Maurice Ravel of his creativity have emerged. Given these facts and the advances in neuroscience that have occurred in the six decades since this paper was published, it seems appropriate to look at this publication from that perspective.

He begins with “the artist who uses the common tool of language, words, and sentences, i.e. the writer.” His example is that of a contemporary author whom Alajouanine followed for over 10 years, but, as he was still alive, his identity could not be exposed and his literary position could only be sketched. His patient while quite young—having attained a foremost rank in French contemporary literature through his poems, and essays on foreign literature, —suffered a right-sided hemiplegia with aphasia. At first he could only utter: “Bonsoir les choses d’ici bas.” His reading ability in several languages, French, Italian, English, and Spanish, rapidly recovered. Spoken language recovered only partially, with “impaired synthetic construction.” Written language followed a similar pattern, and could only be written with the left hand (implying, though not stated, that the patient was right-handed). Alajouanine felt his patient’s memory, aesthetic sense, and judgment were intact but the possibility of literary artistic realization had been abolished. “Conversation is possible, but there is a synthetic reformation of the agrammatic type.” He summarizes his patient’s illness as a case of Broca’s aphasia.2 Alajouanine reminds his listeners of Charles Baudelaire, whom he considers the greatest poet of the 19th century and “who was at the height of his artistic creativity when he suffered a right-sided hemiplegia with aphasia and was reduced to uttering one word, a curse.”

|

|

Valery Larbaud (1881–1957) |

We now know that this first patient was Valery Larbaud (1881–1957), a well-known and influential writer of the first part of the 20th century, who through his love of travel and extensive knowledge of language introduced a wide range of great writers to the French and Western European literary scene.3 In 1935 he produced a French translation of James Joyce’s Ulysses. “On a hot afternoon in August of 1935 at the age of 54 while walking in the garden adjacent to his Latin Quarter apartment, he suffered a cerebrovascular accident that left him with a hemiplegia and aphasia.”4 He survived another 22 years after his stroke, but never regained sufficient ability to write or dictate anything. His stereotyped utterance—Bonsoir les choses d’ici bas—not rare in patients with aphasia (sometimes referred to as a “leitmotiv”) fascinated Alajouanine. It is roughly translated “Farewell, material things from this earth” and is striking for its haunting literary flavor. This sophistication contrasts with Broca’s seminal patient, Leborgne, who could only utter “Tan-tan” for which he was nicknamed. Alajouanine published a book about Larbaud in 1973, many years after the writer’s death, and indicated that Larbaud pronounced his leitmotiv—Bonsoir les choses d’ici bas—perfectly in a rapid involuntary fashion both in an effort to speak and as an answer to a question.5 The famous French neurologist Pierre Marie (1853–1940), whose name is associated with eponyms such as Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, had written a series of prominent articles asserting that patients with aphasia were demented, and Alajouanine never lost an opportunity to contradict his teacher by insisting that Larbaud retained normal intelligence.

Alajouanine’s second case history is that of the famous musician Maurice Ravel, whom he had followed for over two years.6 Ravel is described as having been “struck down by an aphasia” without a trace of paralysis and without hemianopia. His aphasia was a Wernicke’s aphasia of moderate intensity.7With the help of two musicians, a favorite pupil and a neurologist with great musical ability, Alajouanine studied musical tune recognition, musical dictation, note reading and solfeggio piano playing, and dictated musical writing (spontaneous and copied). Ravel retained excellent recognition for pitch or rhythm, and immediately detected subtle mistakes in compositions he had written when they were inserted into his music. In explaining the errors inserted into his music, his speech was described as difficult and halting. His piano playing and his ability to write or copy music were severely impaired. He stated that tunes come back quite easily, and he could hear them “singing in his head.” He retained his ability to hear, criticize, and enjoy music. His severe disturbance in expressing his musical thinking arrested further artistic production.

Alajouanine believed that Ravel’s illness belonged to a group of cerebral atrophies accompanied by “ventricular enlargement” but quite different from Pick’s disease.8 This reference to ventricular enlargement has led to speculation that Ravel had undergone pneumoencephalography. Pneumoencephalography was developed in 1919 by the American neurosurgeon and student of Harvey Cushing, Walter Dandy. If indeed Ravel had undergone this examination, radiologic films or reports have never been discovered.9

|

|

Joseph-Maurice Ravel (1875–1937) |

We know that Ravel was seen by many other neurologists, including the pioneering French neurosurgeon Thierry de Martel (1876–1940), who advised against any surgical intervention. Ravel’s brother Edouard and other close associates consulted another prominent neurosurgeon, Clovis Vincent (1878–1947), who advised surgical intervention on the slim chance that Ravel might have a tumor. At the age of 62, Ravel entered a clinic on rue Boileau in Paris scheduled to have neurosurgery. On Monday, December 20, 1937, the operation was performed.10 Ravel briefly regained some minimal level of consciousness, but was unable to swallow or take nourishment and lapsed into a coma. He died in the early morning hours of December 28, 1937. Vincent’s operative protocol is now available and reveals that the surgeon exposed a right frontal bone flap revealing a slack brain without actual softening in the area displayed. The gyri were separated by edema but not atrophied. An attempt was made to inflate the right lateral ventricle with 20 cc water (saline) but did not succeed despite multiple attempts. No tumor was found and no biopsy was taken.

Ravel’s neurologic illness has been a continuing source of fascination in the neurological literature. In addition to his fame as composer, the expanding classification of cortical degenerative diseases has led to continued speculation as to the diagnosis. Since no biopsy or autopsy was performed, the precise diagnosis will never be known. Recent developments have led to a protein-based classification of neurodegenerative disorders. “Tau proteins” seen in corticobasal and frontotemporal dementia are referred to as tau pathologies, and it has been proposed that Ravel may have suffered from one of these disorders. There is also a body of literature attempting to see signs of Ravel’s neurological decline in two of his later compositions, Boléro and his Concerto for the Left Hand and Orchestra.11 This notion has been challenged by others who see these pieces as highly original works reflecting Ravel’s compositional mastery.

The painter who was Alajouanine’s third patient is described as one of the most representative artists of the French contemporary school. While he does not disclose the artist’s name, he praises him for “originality of matter, technical qualities of realization and intense individualism of his works.” He drops a broad hint as to his identity by characterizing him as expressing the poetry of the Normandy coast. In 1940, the patient at age 52 was “suddenly deprived of his language after two short and transient spells. His aphasia was of the Wernicke type without any phonetic trouble and right-sided hemiplegia, but with a slight hemianopic defect.” Spoken and written language was much impaired. Memory, judgment, and taste were intact. He stopped drawing briefly when a transient apraxia developed, but subsequently “perfect preservation of pictorial artistic realization” returned despite a severe and persistent aphasia. Alajouanine maintains: “According to connoisseurs, he has perhaps gained a more intense and acute expression.”

|

|

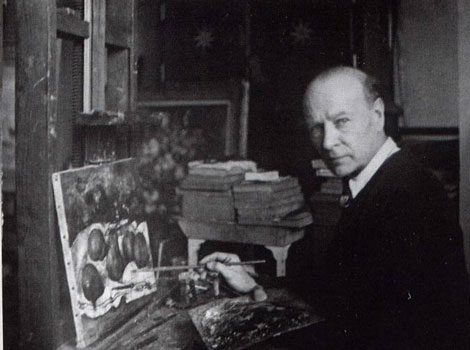

Paul-Elie Gernez |

Thanks to a paper by François Boller the identity of Alajouanine’s painter is now known to be Paul-Elie Gernez (1888–1948).12Gernez was born in a small village near Valenciennes (Northern France) into a humble family, and there is no evidence that his parents had any artistic talent. François Boller confirms the clinical observations in Alajouanine’s 1948 publication and quotes Gernez’s description of his condition: “There are two men inside me, the one who paints, who is normal while he is painting, and the other one who is in a vague state, who is lost, who does not stick to life. . . . When I am painting I am outside my life; my way of seeing things is even more intense than before; I find everything again; I am a whole man.” He resumed painting and continued to paint until his death eight years later in 1948. Boller disagrees with Alajouanine’s assessment of the artist’s post-stroke paintings. While he finds them technically proficient, he also believes they are more concrete and realistic than the dream-like quality found in his earlier work. Today it is recognized that the effect of cerebral damage and aphasia on visual, visuospatial, and drawing capacity is greater in untrained versus professionally trained individuals.13

In a review of the literature on the effects of stroke and aphasia on professionally trained artists, Boller extends Alajouanine’s conclusions, finding the reported results in the literature to be quite variable. Alajouanine begins his conclusions by acknowledging that the aphasia is different in his three cases, but maintains that his functional analysis is still valid. His three subjects have in common a “language trouble” that spares their personality, aesthetic sensibility, memory, and judgment. Art is “the expression of individuality by way of appropriate technique.” Literary art is entirely dependent on language and the synthetic disturbance; “agrammatism” is a major obstacle in artistic realization. For the composer, musical language is made up of signs and musical phrases representing a “superior symbolism.” Graphic transcription of a musical work needs scriptorial ability similar to literary writing, and in the composer this was further hampered by his apraxia. For the painter, visual construction made up of drawing, composition, and color does not involve the use of symbolic language. The different neurophysiological processes involved in artistic realization in the writer and the composer on the one hand and the painter on the other (whose aphasia has not touched his visual perceptions) explains the difference in their ability to continue to be productive.

Viewing this paper from a vantage point of more than six decades, it can be seen that great progress has been made in the understanding and classification of aphasia. The wide variations in individual cases make generalizations based on three patients impossible. Alajouanine characterizes the writer as suffering from Broca’s aphasia and the musician and painter from Wernicke’s aphasia. Based on the clinical information presented in his paper, it is difficult to know how he reached the diagnosis of Wernicke’s aphasia. The creativity of painters afflicted with a variety of neurological disorders continues to be studied, and their ability to continue effective artistic production varies greatly. Similarly musicians who have been studied with aphasia have both continued and been unable to continue to work.14 Because of the data presented on the impairment of musical perception in Alajouanine’s paper on Maurice Ravel, this paper remains of historical interest to musicologists, music historians, and neurologists interested in the physiological basis of musical perception and in cortical degenerative disorders. With the identity of the writer, Valery Larbaud, and the painter Paul-Ellis Gernez, Alajouanine’s work should serve as a stimulus to further studies into the underlying processes of creativity.

Notes

- Quotation marks around words or phrases without references are taken from this publication. T. Alajouanine, “Aphasia and Artistic Realization,” Brain 71(September 1948): 229–241.

- The terms Broca’s aphasia and Wernicke’s aphasia used in this paper refer to two broad categories of aphasia, motor (Broca’s) and receptive (Wernicke’s) aphasia. Paul Broca (1824–1880) was a French surgeon and anthropologist who identified the speech area localized to the posterior part of the third convolution in front of the fissure of Sylvius that bears his name. Karl Wernicke (1848–1904) at age 26 published a book on aphasia in which he described a sensory aphasia associated with lesions of the superior temporal gyrus of the dominant cortex also known as Wernicke’s area.

- François Boller et al., eds. Front Neurol Neurosci: Neurological Disorders in Famous Artists, vol. 19 (Basel: Karger, 2005), 85–91.

- Ibid., 85.

- T. Alajouanine, Valery Larbaud sous Divers Visages (Paris: Gallimard, 1973).

- Alajouanine never provides the dates he examined Ravel. This would be of interest in correlating his observations with observations on the advance of his illness as seen through the eyes of his close associates.

- See note 2 above.

- Pick’s disease is named for Arnold Pick (1851–1924), a Czech physician, who in 1892 described the disease named for him while investigating a patient’s aphasia. Histologically the disease is characterized by a protein tangle that appears as a large body in neuronal tissue and is referred to as a Pick body.

- A future paper will appear reviewing in greater detail neurological aspects of the illness suffered by Maurice Ravel.

- Controversial aspects as to the exact date that Ravel underwent neurosurgery have arisen as a result of a possible faulty date on Vincent’s operative report on conflicting recollections of his close associates. An in-depth presentation of Ravel’s neurological illness can be found in “The Longstanding Medical Fascination with le cas Rave” in Ravel Studies, ed. Deborah Mawer (Cambridge University Press, 2010), 187–208.

- L. Amaducci et al., “Maurice Ravel and Right-hemisphere Musical Creativity: Influence of Disease on His Last Musical Works?,” European Journal of Neurology 9 (2002): 75–82.

- François Boller, “Alajouanine’s Painter: Paul-Elie Gernez,” J. Bogousslavsky and F. Boller, eds., Front Neurol Neurosci: Neurological Disorders in Famous Artists, vol.19 (Basel: Karger, 2005), 92–100.

- D. Benson, M. Barton, “Disturbances in Constructional Abilities,” Cortex 6 (1970): 19–46.

- Catherine Tzortzis et al., “Absence of Amusia and Preserved Naming of Musical Instruments in an Aphasic Composer,” Cortex 36 (2000): 227–242.

JAMES L. FRANKLIN, MD is a gastroenterologist and associate professor emeritus at Rush University Medical Center. He also serves on the editorial board of Hektoen International and as the president of Hektoen’s Society of Medical History & Humanities.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Spring 2012 – Volume 4, Issue 2

| Sections | Neurology

Leave a Reply