Gregory Rutecki

Cleveland, Ohio, United States

|

| Abandoned German TB sanitarium |

The early twentieth century was an auspicious time for medicine. Physicians of the era would be the first to transform the mysterious “captain of all these men of death” into a living, “breathing” bacillus named Mycobacterium tuberculosis.1 As a corollary of the fundamental discovery, diagnostic and therapeutic innovations began in earnest, and these tools would mature, eventually saving millions of lives. It was a time that first unlocked the potential of chest x-rays, culture media, attempts at immune and collapse therapy, as well a first generation therapeutic adumbration: “TB Sanitaria”–directed at the social and medical woes of urbanization. Although these initial interventions stopped short of antimicrobials, it was an impressive time.

The flurry of medical activity indigenous to that era would be chronicled historically by an American medical pioneer, Dr. Edward L. Trudeau.2 He was a friend of William Osler, a student of Edward Janeway, and medical director of the Saranac Lake Sanitarium. In Europe, the fictional characters of Thomas Mann, each presumably infected by tuberculosis, retreated to The Magic Mountain—a Swiss sanitarium. As a novel, The Magic Mountain can be read on many levels and possesses a rich variety of literary, medical, and historical textures. On one hand, it is clearly German, intimately informed by the German Romantic Movement and illustrious predecessors the likes of Goethe, Schlegel, Heine, and Nietzsche.3 But Mann also deliberately chose tuberculosis as the essential cultural backdrop for his novel, having had a personal sanitarium experience himself.4 Despite tuberculosis-as-metaphor– reflecting a decaying European society soon to be crushed by World War I–Mann’s attention to medical detail earned him praise. He once commented, “…my ‘dabbling’ with various branches of knowledge has always had a peculiar intensity of empathy which has allowed me to achieve a creative familiarity with new fields that astonished the specialists.”5 Juxtaposition of Trudeau’s Autobiography–reflective of American medical historiography–with Thomas Mann’s fictional account of tuberculosis, at the same time tangible while metaphorical, offers insight into the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in the early twentieth century.

“Consumption” becomes tuberculosis: a lethal background

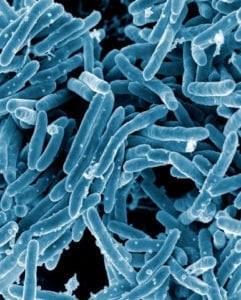

Tuberculosis rendered the late nineteenth-early twentieth century a worst of times. Seventeen to thirty percent of all urban deaths were a result of the mortal bacillus.5 Anywhere from 100 to 500 per 100,000 persons in both Europe and North America were victims of tuberculosis.5 In the words of Humphreys, “…tuberculosis and its devastating effects permeated the culture of the era.”5 The pale, flushed features of those suffering had previously led to the nom de guerre consumption, a vestige of the preceding generation’s pre-scientific perceptions before Koch’s identification of M. tuberculosis.

|

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

Tuberculosis then: the diagnosis

Both Mann and Trudeau identified history and physical examination as critical to the diagnosis of tuberculosis. When Trudeau himself was diagnosed, he had recurrent fevers (to 101 degrees), cervical lymphadenopathy described as “scrofulous,” weight loss, and cough.2 He sought an examination by his medical school professor, Dr. Janeway— who first described Janeway lesions. “Even at that early date Dr. Janeway’s great skill in physical diagnosis was recognized …he began the examination at once… “Yes, the upper two-thirds of the left lung is involved in an active tuberculous process.”2 In The Magic Mountain, the initial approach to a potential infection with tuberculosis is similar: “Well, come along, let me thump you about a bit.’ And the auscultation began. The Hofrat stood leaning backwards, feet wide apart, his stethoscope under his arm, and tapped from the wrist, using the powerful middle finger of his right hand as a hammer, and the left as a support.”6

Although Trudeau makes no mention of x-rays, relying on bacteriological confirmation of M. tuberculosis, Mann alludes to both diagnostic methods in The Magic Mountain. In regard to the chest x-ray: “The breastbone & spine fell together in a single dark column…The thoracic cavity was light, but blood-vessels were to be seen, some dark spots, a blackish shadow… ‘This is nice clean work. Do you see the diaphragm?’ he asked, and indicated with his finger the dark arch in the window, that rose and fell. ‘Do you see the bulges here on the left side, the little protuberances? That was the inflammation he had when he was fifteen years old.’” 6 X-rays informed clinicians regarding the presence of caseation, nodules, cavities, and fibrosis: “…the attraction the bacilli had…(for) the air passages of the throat, bronchial tubes…(and) upon the formation of nodules…caseation…and heal by means of fibrosis…(or) extend the area, create still larger cavities, and destroy the organ.”6 The first generation of clinician-radiologists apparently did not have access to film libraries. X-rays were kept by patients in their rooms.5

After Trudeau’s history and physical examination, he made a definitive diagnosis by culture. “I had learned from Dr. Prudden how to make artificial media—beef gelatin, beef agar…but the first growth of the tubercle bacillus…could be obtained only on solidified blood serum.”2 Trudeau became an expert at diagnosing tuberculosis after examination without x-rays through culture technique. “It is curious how slow physicians were…to accept Koch’s discovery or realize its practical value in the detection of the disease…(he, the patient had) a troublesome cough…and I detected the bacillus…and told him he had tuberculosis …the presence of the bacillus…was irrefutable evidence of the presence of a tuberculous process.”2 Mann’s detail regarding the verified presence of M. tuberculosis was the “Gaffky scale.”5,6 Acid fast staining of sputum was used for diagnosis and estimating the volume of bacilli—the quantitative Gaffky scale then determined the burden of disease.5

Tuberculosis: the earliest attempts at treatment

For both Mann and Trudeau, the regimen of clean air achieved by abandoning urbanization in sanitaria was essential to treating tuberculosis.1 But both sources also looked at validating two other therapies; for Mann, collapse therapy, and for Trudeau immunotherapy with tuberculin–the method supported by Koch. Regarding lung collapse in The Magic Mountain, “Oh, come along,” Joachim said. “I can explain it to you as we go. You looked rooted to the spot! It’s a surgical operation, they often perform it up here… When one of the lungs is very much affected…and the other fairly healthy, they make the bad one stop functioning for a while, to give it rest. That is to say, they make an incision here…I don’t know the precise place, but Behrens has it down fine. They fill you up with gas—nitrogen, you know—and that puts the cheesy part of the lung out of operation.”6 For Trudeau, immunotherapy with tuberculin extract as championed by Koch, did not stand up to carefully designed experiments in an animal model (guinea pig).2 Not surprisingly since Koch was European, “injection,” or immunotherapy is mentioned by Mann.6

Mann’s Dr. Behrens and Edward L. Trudeau: a lesson in empathy

It is difficult to get an intimate glance at the “bedside manner” of Dr. Hofrat Behrens, the medical director in The Magic Mountain. That said, David McCullough offers a glimpse of remaining aristocratic medical arrogance in the person of Guillaume Dupuytren of whom it was said, “For outright physical brutality to a patient, (he) had no equal…If his orders are not immediately obeyed, he thinks nothing of striking his patient or abusing him most harshly.” Then there is Dr. Edward L. Trudeau:

“My brother had a rapidly progressive type of tuberculosis

and my time was soon entirely taken up in caring for his needs

…I bathed him and brought his meals to him…He died one night

…This was my first introduction to tuberculosis and to death…

and I have never ceased to feel its influence. After years it developed

in me an unquenchable sympathy for all tuberculosis patients…”2

Trudeau—who lost a brother to the disease that also afflicted him, seems to have intimately committed himself to a lifetime of compassionate care for those with tuberculosis, “Tuberculosis looms up as an ever-present and relentless foe. It robbed me of my dear ones…it shattered my health. I stood at the death beds of many of its victims whom I learned to love…yet the struggle with tuberculosis…has enabled me to make the best friends a man ever had.”2

A coda

A revisit to the care of tuberculosis in the early twentieth century not only engages the nascent science of diagnosis and therapy, but also serves as a “touchstone” regarding empathy and compassion in the context of care. A recent piece looking at the death of Tolstoy’s Ivan Ilyich raises the same questions while reflecting on then and now:

“The same obstacles that hindered Ivan Ilyich’s doctors hinder

today’s caretakers…A doctor is estranged from the patient…by

…a scarcity of time…Over a century after publication, The Death

of Ivan Ilyich remains poignant to medical educators…it is still

difficult to put ourselves in the patient’s shoes. It reminds us

that the same forces that distanced Ivan Ilyich from his care-

takers continue to separate patients and physicians. The fact

that we have allowed a payment scheme to put more value on

doing to patients than being with patients is to some degree our

fault. Gerasim shows us that the goal of medical education should

be to preserve the capacity to imagine a patient’s suffering…The

Death of Ivan Ilyich is a touchstone, a means of reconnecting with

the sense of calling, and a reminder of how potent being fully present

with the ill can be, a timeless therapeutic tool.”8

Although the diagnostic and therapeutic insights following the discovery of M. tuberculosis—preserved for posterity by Thomas Mann and Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau—remain a historical legacy for our generation, the compassionate demeanor of Dr. Trudeau may be the most valuable characteristic in need of transmission to the next generation of clinicians.

References

- Rutecki GW. Tuberculosis Retrenched at Saranac Lake: A Herald for Contemporary Hospitals. Hektoen International, Fall 2015.

- Trudeau E.L. An Autobiography. Lea & Febiger Philadelphia and New York, 1915. Pages 68-70, 70-71, 202, 184, 29-31, 317.

- Bloom H. (ed.) Modern Critical Interpretations: The Magic Mountain. Chelsea House Publ. New York, New Haven, Philadelphia, 1986. Pages 7-12.

- Dowden SD. (ed.) A Companion to Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain. Camden House, Rochester New York, 1999. Page 110.

- Humphreys P. The Magic Mountain—A Time Capsule of Tuberculosis Treatment in the early Twentieth Century. CBMH/BCHM 1989; 6:147-163.

- Mann T. The Magic Mountain. Vintage Books New York, 1969. Pages 177, 217, 432, 345, 51, 350.

- McCullough D. The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris. Somon and Shuster, New York, 2011, page 114.

- Charlton B. & Verghese A. Caring for Ivan Ilych. J Gen Intern Med. 2009; 25:93-95.

GREGORY M. RUTECKI, MD, received his Medical Degree cum laude from the University of Illinois, Chicago (1974). He completed Internal Medicine training at the Ohio State University Medical Center (1977) and a Fellow-ship in Nephrology at the University of Minnesota (1980). After 12 years of Private Nephrology Practice, he re-entered Academic Medicine at The Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine (awarded “Master Teacher” designation) and became the E. Stephen Kurtides Chair of Medical Education at Evanston Northwestern Healthcare and Professor of Medicine at the Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University. He now practices Medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 10, Issue 1 – Winter 2018

Spring 2017 | Sections | Infectious Diseases

Leave a Reply