Sarah Jane I. Irawa

Parañaque City, Philippines

“And with these hands I keep a memory

Of the ones who’ve done such wrong

Until the judgment comes and all of us are free

I knit a picture of the way it ought to be.”1

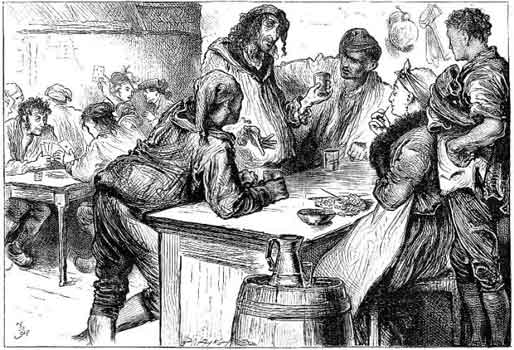

In A Tale of Two Cities, Dickens sketches a portrait of Madame Defarge, “a woman of with a watchful eye that seldom seemed to look at anything, a large hand heavily ringed, a steady face, strong features, and great composure.”2 She seems to be no more than a commonplace spouse helping her husband supervise the affairs of their wine shop.3 Readers often find her sitting in a modest corner where the unmoved shop patrons see her every day, occupied with her knitting, and appearing to be the perfect wife to complement her husband, Ernest Defarge, “evidently a man of a strong resolution and a set purpose; a man not desirable to be met.”2 However, little one’s comprehension perceives that Madame, together with her husband, runs more than a customary wine shop. Theirs is what, at that time, serves as the nucleus of revolutionary goings-on and what, at present, equates, perhaps, to a hideout of terrorist activities. Heretofore, her “watchful eye,” in truth, hardly gazes at nothing; those watchful eyes ferret through every flurry and entity in the shop. And that knitting departs from the plainness of a leisure pursuit; her knitting chronicles the people that, by her judgment, shall suffer the repercussions of their or their relatives’ injustices and cruelties.

So shall suffer they did. Death was manifold; a duke lynched inside his burning chateau, a marquis decapitated with a butcher’s axe, and a queen acceded to Madame Guillotine. And though fatality presented itself in assorted fashions, the slaughtered were of one and the same class—the French aristocracy, La Noblesse. For that time being, France witnessed an unprecedented reversal of roles. The beforehand omnipotent nobility beheld itself at the mercy of the erstwhile impotent third estate.

The third estate accommodates all and sundry not belonging to the clergy or aristocracy; in principle, everyone having no titles—from the peasantry to the bourgeoisie or the middle class, that is. Subsequently, that definition incorporates Madame Defarge into the third class. A tricoteuse, she identifies herself with those Parisian women who sit among the crowd gathered as spectators to the beheadings at the guillotine’s scaffold.4 And, Defarge, just like all of them, is as callous to the victim as she is compassionate to her knitting.

However, as Dickens unknots the strings entangling Madame Defarge’s character, readers discover that there is more to general acrimony in yearning and, eventually, crafting the death of the haughty aristocrats. A glance at her private history offers the allusion of a personal facet in Madame’s desire for retribution.

I was brought up among the fishermen of the seashore, and that peasant family, injured by the two Evremonde brothers, as that Bastille paper describes, is my family. Defarge, that sister of the mortally wounded boy upon the ground was my sister, that husband was my sister’s husband, that unborn child was their child, that brother was my brother, that father was my father, those dead are my dead, and that summons to answer for those things descends to me!5

More so, her vengeful nature cannot be further underlined by these lines,

“It is a long time,” repeated his wife; “and when it is not a long time? Vengeance and retribution require a long time; it is the rule.”6

Vengeance, retaliation, wrath—whichever to call it—conceivably supplied the impetus for Madame Defarge’s ardor to adhere to the ghastly exploits of the French Revolution. She had every reason to do so, and so did many others. So did for instance Mary Tudor, who once seated on the English throne arranged for all outwardly Protestant English men and women to be burned at stake; and so did Germany, cooking the Second World War following the humiliation the Treaty of Versailles.

In a modern psychologist’s jargon, revenge could connote as “the infliction of harm in return for perceived injury or insult or as simply as getting back at another person.”7 But in Madame Defarge’s lingo, revenge means nothing less than “the death of the current Marquis Evremonde in return for the demise of her father, brother and sister.” But why would Madame Defarge and her fellow Parisians permit their hands get tarnished with the aristocrats’ blood and not just wait until the wheels turn and have legal justice reside on their side?

Vengeance, as Kruks expresses it, is “a part of our fundamental biological equipment”8—a niche in humanity more archaic than the Bible. In a much simpler term, it is human nature—something comparable to Newton’s third law of motion or tropism, a plant’s propensity to react to a stimulus.

When someone bears victimization, there are, understandably, two probable responses inherent to the victim—either to impose an affront or injury with degree similar to what was received or to fetch the matter to a higher office tantamount to a judiciary. To wit, the first refers to seeking revenge, the second to seeking legal justice. But unlikely to obtain justice under the vestigial dysfunctional pre-revolutionary French judicial system,9,10 Madame Defarge would perhaps be one with Michael Price in his assertion that “if you live in a society where the rule of law is weak, revenge provides a way to keep order,”11 leaving her with the first recourse—vengeance.

But revenge has further attributes: First, “it is intended to re-equilibrate gains and losses caused by the assault”—the proverbial “eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot”12 Next, “revenge is intended to re-equilibrate power” pertinent to the existing state of affairs in eighteenth-century France. And it also aspires to reinstate the victim’s self-worth devastated by victimization. But the satiating consequence of vengeance is likely transitory, offering but a fleeting sense of pleasure at seeing the perpetrators suffer.13 It also thwarts the seeker from any attempt of progress in life rather than obsess with arranging the destruction of those who have wronged her.11 But this is precisely what she did, feckless of placing her “integrity and social standing” in jeopardy7:

Madame Defarge’s hands were at her bosom. Miss Pross looked up, saw what it was, struck at it, struck out a flash and a crash, and stood alone—blinded with smoke.

All this was in a second. As the smoke cleared, leaving an awful stillness, it passed out on the air, like the soul of the furious woman whose body lay lifeless on the ground.14

So ruined Madame Defarge, born roughly thirty years since, strayed at a fragile age, married a scrupulous man, adhered to the causes of the Revolution, took the law into her hands, and met her demise in lust for vengeance.

Notes

- All Musicals. “The Way It Ought to Be.” http://www.allmusicals.com/lyrics/taleoftwocitiesa/thewayitoughttobe.htm. Accessed January 26, 2013.

- Charles Dickens, A Tale Of Two Cities (Great Britain: Penguin Group, 1994), 40.

- Charles Dickens, A Tale Of Two Cities (Great Britain: Penguin Group, 1994), 42.

- Teresa Mangum, “Dickens and the Female Terrorist: The Long Shadow of Madame Defarge,”Nineteenth-Century Contexts 31, no. 2 (2009): 151, nbhsths.nbpschools.net/download.axd, accessed January 26. 2013.

- Charles Dickens, A Tale Of Two Cities (Great Britain: Penguin Group, 1994), 334.

- Charles Dickens, A Tale Of Two Cities (Great Britain: Penguin Group, 1994), 179.

- Amy L. Cota-McKinley et al, “Vengeance: Effects of Gender, Age, and Religious Background,”Worcester State University: 3, accessed January 26. 2013, http://www.worcester.edu/PsychologyDept/Shared%20Documents/Sample%20experimental%20report.pdf

- Sonia Kruks, “Why Do We Humans Seek Revenge, and Should We?,” Insights 2, no. 9 (2009): 2-3, accessed January 26. 2013, http://www.dur.ac.uk/resources/ias/insights/Kruks7May2.pdf

- Department of Justice. “The French Revolution and the organization of justice.” http://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/pi/icg-gci/rev1/index.html. Accessed February 12, 2013.

- Inna Gorbatov, Catherine the Great And the French Philosophers Of The Enlightenment (Bethesda: Academica Press LLC, 2006), http://books.google.com.ph/books?id=9sHebfZIXFAC&printsec=copyright&hl=fil&source=gbs_pub_info_r#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Michael Price, “Revenge and the people who seek it.” Monitor 40, no. 6 (2009), accessed January 26. 2013, http://www.apa.org/monitor/2009/06/revenge.aspx.

- The Jerusalem Bible, The Jerusalem Bible (Manila: Philippine Bible Society, 1966), 104.

- Ulrich Orth, “Does Perpetrator Punishment Satisfy Victims’ Feelings of Revenge,” Aggressive Behavior 30, (2004): 68, accessed January 26. 2013, http://uorth.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/orth_2004_ab.pdf.

- Charles Dickens, A Tale Of Two Cities (Great Britain: Penguin Group, 1994), 360.

References

- All Musicals. 2013. The Way It Ought to Be. http://www.allmusicals.com/lyrics/taleoftwocitiesa/thewayitoughttobe.htm. (accessed January 26).

- Cota-McKinley, Amy L. Woody, William Douglas and Bell, Paul A. “Vengeance: Effects of Gender, Age, and Religious Background”. Worcester State University: 3, accessed January 2013, http://www.worcester.edu/PsychologyDept/Shared%20Documents/Sample%20experimental%20report.pdf

Department of Justice. “The French Revolution and the organization of justice.” http://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/pi/icg-gci/rev1/index.html. (accessed February 2013) - Dickens, Charles. 1994. A Tale Of Two Cities. Great Britain: Penguin Group.

- Gorbatov, Inna. Catherine the Great And the French Philosophers Of The Enlightenment. Bethesda: Academica Press LLC, 2006. Available online at http://books.google.com.ph/books?id=9sHebfZIXFAC&printsec=copyright&hl=fil&source=gbs_pub_info_r#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Kruks, Sonia. “Why Do We Humans Seek Revenge, and Should We?” Insights. 2, issue 9 (2009). http://www.dur.ac.uk/resources/ias/insights/Kruks7May2.pdf. (accessed January 2013).

- Mangum, Teresa. “Dickens and the Female Terrorist: The Long Shadow of Madame Defarge.” Nineteenth-Century Contexts, 31, 2 (2009). (accessed January 2013).

- Orth, Ulrich. “Does Perpetrator Punishment Satisfy Victims’ Feelings of Revenge,” Aggressive Behavior, 30 (2004). http://uorth.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/orth_2004_ab.pdf. (accessed January 2013).

- Price, Michael. “Revenge and the people who seek it.” Monitor, 40, issue 6 (2009). http://www.apa.org/monitor/2009/06/revenge.aspx. (accessed January 2013).

- The Jerusalem Bible. 1966. The Jerusalem Bible. Manila: Philippine Bible Society.

SARAH I. IRAWA is presently employed at a transnational financial institution as a transitions analyst. Having graduated from De La Salle University with a degree of in Finance, she decides to pursue a career relevant to what she has taken up back in college. On weekends or each time she gets leave from work, Sarah commits herself to her hobbies—reading classical novels and history books and writing—the latter she esteems as the most pleasurable.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 6, Issue 1 – Winter 2014, Volume 14, Issue 1 – Winter 2022, and Volume 16, Issue 2 – Spring 2024

Leave a Reply