Burton R. Andersen

Chicago, Illinois, United States

The accomplishments of the ancient Greeks in literature, science, and government have been widely recognized and admired. Ancient Greek medicine has also been held in high esteem; however, their practice of medicine merits careful examination and comparison with other ancient medical cultures. Different cultures have employed in various ways the sensory modalities used in physical diagnosis, the descriptors used to characterize abnormalities, the organization used to group signs and symptoms into disease categories and syndromes, and the development of surgery. An exploration of Hippocratic and Mesopotamian medical writing reveals interesting differences in emphasis on the description of signs and symptoms, disease classification and treatment, and use of surgery. This article will explore some of these differences through the writings of Hippocrates and other practitioners in the Hippocratic School1 and the medical writings from ancient Mesopotamia.

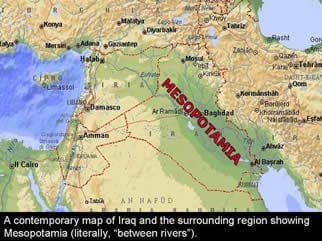

Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (now modern Iraq), was first inhabited by the Sumerians in about 4500 B.C.E. The origin of the Sumerian people remains a mystery, and even their language does not appear to be related to any known language group. They developed a technically sophisticated irrigation system that produced an abundance of food, enough not only to feed the Sumerians but to use for trade. They also invented the first pottery wheel, chariot, and architectural arch.

The Akkadians, a Semitic speaking people, enveloped and subsumed the Sumerian culture and written language. They eventually divided into the northern Assyrians and southern Babylonians. The oldest Sumerian medical text discovered is from the Ur III period (2112-2004 B.C.E.); however this text is part of an older tradition of medical scholarship. The Akkadians improved Sumerian medicine which reached its golden age during the Middle Assyrian and Middle Babylonian periods (1430-1050 B.C.E.).

As the Sumerians were the first people to develop written language, Sumerian/Akkadian medicine is the oldest recorded medical literature known. Much of their medical literature is available for study as their cuneiform writing was inscribed on clay tablets that were either sun dried or kiln fired. This process made them capable of surviving almost indefinitely unless subjected to physical force.

An important source of medical information during the golden age of Mesopotamian medicine was a series of 40 tablets that constituted a “textbook” of medicine. It covered the diagnosis and prognosis of illnesses in all areas of medicine in an organized head-to-toe fashion. This Mesopotamia “textbook” of medicine is a major source of information when comparing the two medical cultures. The writings that are part of the Hippocratic corpus have all been used but of most value are the 42 case reports found in Of the Epidemics. Since most of the cases described in this Hippocratic text were infections (all had fevers), it gives us some expectations of the findings and diseases that these individuals were likely to have suffered.

Use of the five senses

Humans have five senses available to observe their environment and for physicians to observe their patients: sight, hearing, smell, touch, and taste. However, the senses are employed with varying emphasis in Greek and Mesopotamian literature. Of the senses, ancient and modern physicians rarely describe symptoms in terms of taste. Smell and hearing conversely are used in different cultures with varying emphasis. For instance, the 42 clinical cases in Of the Epidemics and the majority of sections of the Hippocratic corpus (with the exception of cough) ignore the senses of smell and hearing. The ancient Mesopotamian physicians, however, recorded both smell and hearing in their diagnoses. They described the “stink” often associated with an infected wound, the sounds of abnormal breathing and the noise of gastro-intestinal dysfunction:

If a person is sick with stink, (that means) stink said of a wound.2

If a mighty illness afflicts him so that he has a reduced appetite for bread, his lungs sing like a reed flute, and fever continually afflicts him daily in winter, he will die.3

If a person’s insides are continually bloated, his intestines rumble, his intestines continually make a loud noise, “wind” groans in his stomach and “butts” into his anus, that person is sick with pent-up wind, to cure him.4

Both medical cultures used sight and touch for observations of physical abnormalities. Let’s now explore both the Hippocratic and Mesopotamian texts, comparing their descriptions of various physical findings.

Physical findings

The physical findings or abnormalities observed by a physician are important factors in identifying a disease. The physician’s attention to detail and care in describing the abnormalities are critical in permitting an accurate diagnosis. Despite the importance of physical findings, Hippocratic and Mesopotamian physicians differed widely in their descriptions of physical assessment. With the exception of excretions, Mesopotamian physicians described symptoms in far greater detail than Hippocratic physicians, using categories traditionally used by modern medicine for diagnosis. I will compare five physical findings described in each tradition’s case studies: temperature, pulse, skin lesions and cough/abnormal breath sounds, and excretions.

Temperature:

All 42 of the clinical cases in Of the Epidemics had fever. In nine cases only fever was mentioned with no other description. In 27 cases the fever was “acute” and in six others “ardent.” There was no mention of any body part being warmer than another. Cold extremities, however, were described.

The ancient Mesopotamian physicians considered four levels of fever: burning, very hot, hot, and lukewarm. They also indicated which body part had an elevated temperature.

If he is sick for one, two, and then three days and subsequently the burning fever lets up from his body but after it has left, the burning fever does not let up from his head (and he continues this way) for three days (or) for six day (altogether), he will die.5

Pulse:

None of the cases in Of the Epidemics described pulse. Since all the patients were febrile and probably all infected, it is likely that many had rapid pulses, some strong and others weak and possibly irregular. These abnormal pulses must have been detectable at many sites; yet nothing about this was mentioned.

Ancient Mesopotamian physicians paid great attention to pulses. Pulses were noted to be either rapid, slow, strong, weak, irregular, or absent, and were palpated in all four extremities, the abdomen and in seven locations on the head, face, and neck.

If the blood vessels of his feet go and those of his hands are slow, he will speedily die.6

If his chest is clear, the blood vessels of his temple have collapsed, blood incessantly flows from his mouth/nose, and his heart incessantly shudders, “hand” of Marduk; he will be worried and die.7

If his upper abdomen is hot and the blood vessels of his temples, his hands, and his feet continually feel like they are pulsating and his eyes bother him.8

Skin lesions:

The skin is considered by modern physicians to be a window into the body, since many skin abnormalities can be seen with internal diseases. The care taken to describe skin lesions can go a long way to identifying a disease or syndrome.

There are only six skin abnormalities listed in the 42 cases in Of the Epidemics. One case mentions only a red rash with no location or any other characteristics. Two cases described a red rash on the face. In one case a red rash was described along with small bullae, but no location was mentioned. Finally, there were two cases with parched and tense skin, but again no location was mentioned. In 42 infected patients, it seems likely that many more skin lesions must have been present.

Ancient Mesopotamian medical writings have identified more than 50 different terms describing skin lesions. Descriptions include color, distribution, scaling, ulcers, bullae/vesicles, itching, elevation, wet/dry, and duration of the lesions:

If a person’s feet continually have fever, they are reddish and he cannot stop scratching and they are full of sores, he is sick with.9

If a woman gives birth and from the beginning the child is full of black spots.10

If a person’s forehead is full of pockmarks.11

Cough/Abnormal breath sounds:

Only three patients in Of the Epidemics were said to have had a cough, described as dry, productive, and slight. Five of the 42 cases showed abnormal breathing, but only frequency and depth of respiration were mentioned. Nothing was said about the character of the sound.

Ancient Mesopotamians physicians described coughs that were barking, brassy, dry, and productive. Rate and depth of breathing was often mentioned, but in addition breath sounds were variously described as: wheezing, gurgling, growling, gasping, croaking, and roaring.

If a person is sick with wheezing and barking cough so that the windpipe is full of wind, he has barking cough and has brassy cough and has phlegm.12

If a person gurgles like the waves of a canal . . .it will turn to anger of a goddess; to save him.13

If he has been sick for five or ten days and gasping respiration persists in being continuous for him, he will die.14

Excretions:

Although there are other physical findings that could be compared, the trend of poor and limited descriptions provided by Hippocratic physicians when compared with ancient Mesopotamian physicians holds true. The only exception is when the Greek physicians described materials produced by vomiting, defecating, or urinating. They invariably included the color, consistency, amount, presence of “bile” or blood, and the nature of any solid material and whether it floated or settled in the fluid. In many of the patient descriptions in Of the Epidemics half of them related to the appearance of the patients urine, stool and/or vomitus:

Case II. – Silenus lived on the Broad-way, near the house of Evalcidas. From fatigue, drinking, and unseasonable exercises, he was seized with fever. . . .On the first day the alvine discharges were bilious; unmixed, frothy, high colored, and copious; urine black, having a black sediment; he was thirsty, tongue dry; no sleep at night. . . .On the fifth, stools bilious, unmixed, smooth, greasy; urine thin, and transparent; slight absence of delirium. On the sixth . . . no passage from the bowels, urine suppressed, acute fever. . . . On the eighth . . . a copious discharge from the bowels, of a thin and undigested character, with pain; urine acrid, and passed with pain; extremities slightly heated; sleep slight, and comatose; speechless; urine thin, and, transparent. On the ninth, in the same state. On the tenth, no drink taken; comatose, sleep slight; alvine discharges the same; urine abundant, and thickish; when allowed to stand, the sediment farinaceous and white; extremities again cold. On the eleventh, he died15 [Emphasis added].

The reason for their obsession with excretions remains uncertain but may relate to their theory of humors.

Ancient Mesopotamian physicians also described the appearance of urine and stool, including color, volume, and the presence of “bile” or blood. Seldom was there mention of solid material in urine. A much smaller portion of their description of patients was devoted to the appearance of excretions than is found in Hippocratic writings.

Disease names and syndromes

How ancient physicians organized medical findings also helps to understand their approach to treatment. Generally the physician will employ a therapy to treat a condition because it has some characteristic that is believed to be susceptible to the medicine. Some medical cultures directed the treatment at individual signs or symptoms while in others the signs and symptoms were organized into diseases and syndromes that were then the object of treatment.

No disease names or syndromes are assigned to any of the 42 cases in Of the Epidemics. This generally holds true for the Hippocratic corpus, with the exception of conditions that involve specific anatomical sites such as a dislocated joint, or a broken bone. Rather than developing therapies directed against a specific disease or syndrome, the Hippocratic physician directed his therapies to the treatment of symptoms such as fever or diarrhea.

Medicine in Mesopotamia was organized into diseases and syndromes, and treatment was symptomatic only when the disease was considered to be incurable. Their 40 tablet “textbook” was basically a listing of diseases and syndromes. When two or more syndromes were similar, the textbook compared signs and symptoms to illustrate their differences. Diseases and syndromes were commonly named after gods, demons, and spirits; but it appears that the characteristics of the disease or syndrome were first established by the signs and symptoms, and only then was it assigned the name of a god, demon, or spirit.

Examples of Mesopotamian syndromes are the following:

A.GA.ZI – This is the Sumerian word for peptic ulcer disease:

If a person eats bread and drinks beer and then he continually produces mucus, he incessantly vomits mucus, he shows mucus and black blood, he has constriction of the mouth of the stomach (pylorus), and his upper abdomen burns, burns hotly, stings and hurts him, that person is sick with A.GA.ZI.16

Bushanu

This word means “stinking” in Akkadian, and it has evolved into the name of a three-part syndrome referring to a throat disease that attacks the airway, throat/mouth or gums. It seems likely that this represents three known modern diseases that characteristically produce a foul odor and membranes, namely, diphtheria, herpetic stomatitis, and Vincent’s angina (trench mouth):

Mighty is the affliction of bushanu. It seized the uvula like a lion; it seized the hard palate like a wolf. It seized the soft palate; it seized the tongue. It set up its throne in the windpipe.17

If a person’s mouth is sore . . . if his mouth is full of vesicles.18

If sores and bushanu grip a person’s teeth and blood comes out between his teeth.19

Touched in the Steppe

There is a series of 16 references entitled “Touched in the Steppe” that refer primarily to abnormal changes in the patient’s hair. One reference describes a patient with a wasted and gaunt face. In all cases the prognosis is fatal or very grave. It seems very likely—especially since the steppe is an area of limited food resources—that this syndrome is due to protein malnutrition (Kwashiorkor). The hair changes described are all known to occur in protein malnutrition:

If the hair of his head is red, he will die. If the hair of his head is red and frizzes, he will die.20

If his face falls flat against his skull, he was “touched in the steppe”; he will die.21

Surgery

The Hippocratic Corpus devotes many sections to both general principals of surgery and to specific surgical techniques. Matters such as lighting, clothing, cleanliness, and decorum during surgery were discussed. Most of the specific surgical techniques involved orthopedic procedures such as joint dislocations and fractures. The techniques used and the anatomy involved were described in great detail. Many devices were crafted to aid the surgeon in reducing the dislocation or fracture. Other surgical techniques were listed such as the drainage of abscesses, and the treatment of rectal fistulae and hemorrhoids.

The Mesopotamian physician performed surgery, but the details of their techniques were minimal. Abscesses as well as pulmonary empyemas were drained. Casts were applied to broken bones, and nose bleeds were packed. There is a reference that suggests that Caesarian sections were performed, but the nature of the description leaves some doubt as to exactly what was done. It is likely that only the fetus might have survived such a procedure. The limited descriptions of surgical techniques and procedures in the Mesopotamian medical literature suggests that their surgical performance was also limited in scope and quality.

Ancient theories of disease causation

Hippocratic physicians developed a number of theories that supported their therapeutic approaches. The only one to be discussed in this article is the most prominent and influential one, the Theory of Humors. In brief, this theory states that the body contains four humors: phlegm, yellow bile, black bile and blood, and these were derived from food. Health depended on maintaining these humors in proper balance. The origin of this theory is unclear, but it may be derived from the physician’s extreme concern with the nature of bodily excretions. Certainly blood and “yellow” bile may be present in vomitus, stool, and urine. Blood in vomitus and stool, if it has been denatured by stomach acid, will look dark brown or black, which may be the substance described by these physicians as black bile.

Purging may have been practiced in an attempt to achieve a balance of humors, but it was certainly not developed based on clinical observations of improvement after purging. Almost no diseases will profit from the induction of vomiting or defecation. The practice of blood-letting may have evolved from observations of patient survival following nose bleeds. In the Of the Epidemics, of the 10 patients with nose bleeds seven survived. This is a much better overall survival rate than survival for the total 42 cases (17/42). But just like purging, it is a rare clinical situation in which bleeding can be expected to improve a patient’s condition. It is more likely to cause worsening and death.

The physicians of ancient Mesopotamia did not generate unfounded theories about the causes of diseases. They organized the signs and symptoms into syndromes and assigned a god, demon, or spirit as a name. They had a very empiric approach to illness, and established treatment by trial and error.

Summary

Mesopotamian (Sumerian/Akkadian) physicians when compared with Hippocratic physicians were consummate diagnosticians and classifiers of disease. They practiced an empiric approach to therapy that is very similar to modern physicians, namely, use whatever works, but they applied treatment in an organized fashion. Hippocratic physicians treated symptomatically with treatment based on theories, and they did not consider diseases as discrete and separable entities.

Mesopotamian physicians practiced surgery but appear to have been much more primitive in their approach when compared to Hippocratic surgeons. The Hippocratic Corpus has many careful descriptions of surgical techniques, equipment, and bone and joint anatomy to validate their excellence as surgeons.

Notes

- The Genuine Works of Hippocrates. Trans. Francis Adams. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins Co., 1939.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 64.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 184.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 125.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 28.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 536.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 536.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 173.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 211.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 217.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 227.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 178.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 181.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 181.

- The Genuine Works of Hippocrates. Trans. Francis Adams. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins Co., 1939. 112.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 135.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 40.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 41.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 41.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 157.

- Scurlock, JoAnn and Burton R. Andersen. Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005. 157.

BURTON R. ANDERSEN, MD, is a Professor of Medicine and Microbiology at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He is also a specialist in Infectious Diseases and is a member of that section at UIC; he is the Research Subject Advocate in the Clinical Research Center. He is the co-author of Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine published in 2005 by University of Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago. He was also the Principal Investigator for a three-year research grant on Ancient Mesopotamian medical therapies by the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Winter 2010 – Volume 2, Issue 1

Leave a Reply