Elisabeth Brander

St. Louis, Missouri, United States

Of the many distinguished anatomists who worked in the Netherlands during the European Enlightenment, Frederick Ruysch and Govard Bidloo were the two most remarkable. They were contemporaries and aware of each other’s work,1 but at first glance their aesthetic approaches to anatomy seem wildly different. Bidloo (1638-1731) produced an atlas known for its extreme realism, eschewing depictions of lifelike corpses posing against elaborate backgrounds in favor of showing the graphic horrors of dissection. Ruysch (1649-1713) produced a “cabinet of curiosities” in which he showed a Baroque fantasy of the strange and grotesque. Despite their apparent differences, however, both artists were influenced by the already existing trends in early modern Dutch art and are but two sides of the same coin.

There is nothing new in thinking of anatomical illustrations in terms of their aesthetic rather than scientific merits. Art and anatomy have indeed had a long-standing relationship. During the Renaissance, anatomists often hired trained artists to illustrate their great atlases, for anatomical figures were expected to be beautiful as well as scientifically accurate,2 a concept that appeared to spectacular effect in Andreas Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica. This atlas, first published in 1543, was notable for both its anatomical accuracy and the physical beauty of its illustrations. Henceforth anatomical atlases needed to strive for a high level of artistry as well as scientific detail, as clearly seen in the great 17th and 18th century anatomical works.

It is not surprising that the publications of Ruysch and Bidloo show the influence of prevailing artistic sensibilities.3 One of the hallmarks of 17th century Dutch paintings is a sense of realism, to show what the eye saw rather than an imagined landscape that told a religious or historical story.4 This drive to depict the reality of the world went hand in hand with a desire to uncover its hidden layers. In Dutch still lifes, lemons are peeled to show their pulpy interiors; cheeses and pies are cut into rather than left whole; and glass vessels are shattered to reveal a multitude of edges and surfaces.5 (Fig.1) And just as artists strove to show the many facets of the world around them, anatomists and scientists aimed to illustrate the hidden parts of the body and the unusual aspects of the natural world.

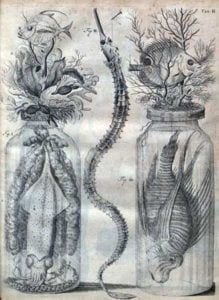

The Enlightenment-era desire to come to a better understanding of the world around them is very apparent in the work of Frederick Ruysch. Ruysch received his medical degree from the University of Leiden in 1664 and became praelector of anatomy for the Amsterdam surgeon’s guild in 1666. Although he was a lecturer in anatomy, he was best known for his anatomical and zoological cabinet featuring strange and somewhat macabre displays. These displays, known to us today through the printed published catalogues, feature whimsical scenes such as fetal skeletons playing violins and fauna preserved in jars topped with forests of shells, twigs, and flowers (Fig. 2 & Fig. 3). The effect is admittedly bizarre, but also perfectly in line with prevailing aesthetic trends in 17th century Dutch still lifes.

The illustrations of Ruysch’s cabinet are similar to Dutch still lifes in their execution and desire to accurately depict the world—to show “what the eye saw.” In his paintings, this desire takes form of paying attention to every detail—for example how light falls on a silver cup or how pies are cut open instead of being left whole. The illustrations of Ruysch’s specimens pay similar attention to the minutiae of the various exotic specimens he preserved. Like the paintings, the engravings capture much detail, from the veins in the placenta one fetal skeleton is using as a handkerchief to the unique patterns found on each individual seashell. Even the overall composition of the tableaux and the paintings is strikingly similar. Dutch still lifes frequently show a plethora of material objects tumbled together in a haphazard, yet artistic fashion—cups are knocked over on their sides; fruit spills over the edges of a plate; and napkins are tossed carelessly onto tables. The same sense of controlled chaos is apparent in Ruysch’s displays, where skeletons pose against coral reefs in the company of birds and insects, and shells and fish occupy strange forests on the top of embalming jars. Thus Ruysch illustrations are comparable to a traditional still life painting.

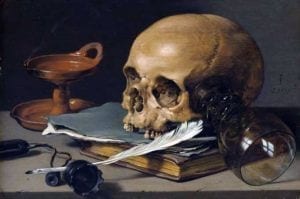

Another similarity between the two artists lies in a shared theme of morality. Golden Age Dutch vanitas paintings contain the moral message that our mortal life is brief and we should not be too attached to worldly things. To remind viewers of the transience of life and fleeting nature of earthly pleasures, these paintings depict skulls and wilting flowers or half eaten fruit (Fig. 4). The Ruysch tableaux likewise use human and animal remains, and small fetal skeletons presiding over their strange kingdoms as poignant reminders of the frailty of human flesh.

At the opposite end of Ruysch’s fantastical world is the work of Govard Bidloo. Bidloo was apprenticed to an anatomist in his hometown of Amsterdam,6 received his medical degree from the University of Franeker, then served as lecturer of anatomy in The Hague and professor of anatomy and medicine at the University of Leiden, a post he held until his death. His greatest accomplishment was his Anatomia Humani Corporis, first published in 1685. At first glance, this large-scale atlas with relatively straightforward depictions of the dissected human form seems very different from Ruysch’s playful displays; yet Bidloo’s stern aesthetic is just another interpretation of the same artistic trends that influenced Ruysch.

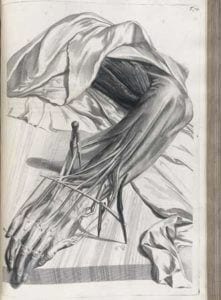

Bidloo’s atlas represents a paradigm shift in the style of anatomical illustration. In the 16th and first half of the 17th centuries, anatomists such as Estienne, Vesalius, and Casserius took a somewhat playful approach to anatomical illustration. Their corpses posed against elaborate backdrops as though still alive, holding up flaps of skin and peeling away layers of muscle to reveal their innards to the viewer. Bidloo’s Anatomia broke away from that theatrical approach. Rather than softening the violating nature of dissection by showing artistically rendered lifelike corpses, Bidloo had artist Gerard de Lairesse depict the corpses’ experience on the dissection table in all of its grisly detail. The pins and clamps used to position the various body parts on display rather than discreetly erased from sight, flies rest on bits of flesh, and limbs are shown severed from the rest of the body.7 (Fig. 5) There is no attempt to soften the fact that the viewer is looking at dead bodies that were cut open and taken apart, and violation of the human form is put front and center.

Although the stark, almost brutal style of Bidloo seems to be at complete odds with Ruysch’s more playful approach, it shares the same underlying influences. Like the illustrations of Ruysch’s cabinet of curiosities, the engravings in Bidloo’s atlas are imbued with Dutch artistic realism and morality. Bidloo broke new ground by portraying the dissected body as it was, showing the various pins, needles, and ragged edges of flesh that were part of the dissection process, striping the allegory from dissection in order to show the unadorned interior of the body. Just as Dutch artists peeled fruit and cut cheeses and bread to show the interior of an object, so Bidloo peeled away the human skin to reveal the underlying muscles and bones, treating the corpse as just another inanimate object just like a piece of fruit.

Bidloo’s atlas is also very moralistic in tone. While the bodies seen in Vesalius or Casserius have an almost sanitized appearance to them, Bidloo’s corpses evoke the unpleasantness of death and dismemberment. According to historian Rina Knoeff, this stylistic choice can be explained at least partially by Bidloo’s Mennonite beliefs. In addition to believing in a strict moral code that decried superfluous displays of artistry, the Dutch Mennonites had a particular interest in tales of martyrdom that emphasized the harsh circumstances of early Christians’ deaths. This interest in unadorned suffering is evident in the Anatomia.8 The aesthetics of Bidloo’s atlas, which emphasizes the body’s vulnerability to the knife, serves as an anatomical representation of the mortification of the flesh. Like the vanitas paintings and Ruysch’s fragile fetuses, de Lairesse’s beautifully gruesome plates are a commentary on the ultimate supremacy of death.

In the end, the similarities between Ruysch and Bidloo outweigh the cosmetic differences. Bidloo’s atlas is more austere than Ruysch’s morbidly playful dioramas, but shares the interest in depicting realism and morality. Both anatomists were interested in showing something that the average citizen would never see, the inside of the human body or an exotic biological specimen; and both convey messages on the fleeting nature of human life. Although different on the surface, the aesthetic approaches employed by these two great anatomist are both, in the end, quintessentially Dutch.

End notes

- According to Tim Huisman, Ruysch was among the critics of Bidloo’s atlas, and felt that some details were incorrect in their execution. Tim Huisman, The Finger of God: Anatomical Practice in 17th-century Leiden (Leiden: Primavera Pers, 2009), 109.

- Ludwig Choulant. History and Bibliography of Anatomic Illustration, trans. Mortimer Frank (New York & London: Hafner Publishing Company, 1962), 30.

- Michael Sappol provides a very good discussion of how Dutch artistic sensibilities influenced Dutch anatomical art in his work Dream Anatomy (Bethesda: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, 2006), especially pages 40-46.

- Svetlana Alpers. The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983), xx.

- Alpers, The Art of Describing, 90-91.

- During which time he heard Ruysch’s anatomical lectures.

- Michael Sappol. Dream Anatomy (Bethesda: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, 2006), 28.

- Rina Knoeff. “Moral Lessons of Perfection: A Comparison of Mennonite and Calvinist Motives in the Anatomical Atlases of Bidloo and Albinus,” in Medicine and Religion in Enlightenment Europe, eds. Ole Peter Grell & Andrew Cunningham (Aldershot & Burlington: Ashgate, 2007), 128, 130.

ELISABETH BRANDER, MA/MLS, graduated from the University of Maryland with a Masters in Library Science and a Masters in History focusing on early modern Europe, and is now the Rare Book Librarian at the Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine. Her research interests include the connection between medicine and magic and the changing depictions of the female form in anatomical illustration.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 6, Issue 2 – Spring 2014 and Volume 15, Issue 3 – Summer 2023

Leave a Reply