Vivian McAlister

London, Ontario, Canada

By the time of his death in 1824, seven years after writing a monograph on the “shaking palsy,” James Parkinson was nearly forgotten.1 Even today, few people know anything about him, despite the fact that his medical eponym is well known. Over 100 years ago, this knowledge gap troubled Leonard Rowntree, a medical student at Western University in London, Ontario. When asking knowledgeable professors and visiting speakers if they knew anything about Parkinson, some guessed that he was a country apothecary who happened to describe a few patients who shared a similar condition.

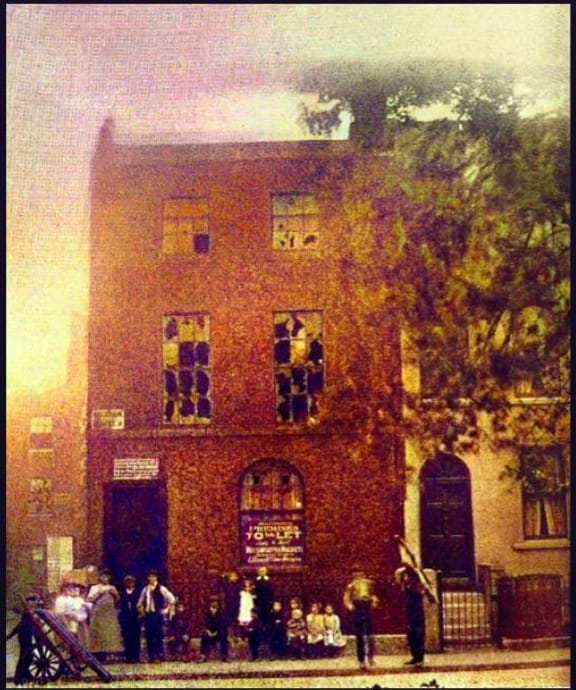

Prominent neurologists tried to address the issue on the bicentenary of Parkinson’s 1755 birth by erecting a memorial tablet in his local church, giving the appearance of a continuity of memory.2 Their request to place a blue plaque on his birthplace was denied by the local council because Parkinson’s house had been replaced by a modern structure. A photograph of the original house, in a dilapidated state, is held by the Wellcome Collection.3 The group erected a private blue plaque with the cooperation of the owner of the new structure.

Rowntree continued to inquire about Parkinson when he moved to Johns Hopkins University, where his own research into kidney function under the direction of John Jacob Abel was highly successful. Soon he was traveling to London to present their work at conferences and in 1910 took the opportunity to inquire about Parkinson at the British Museum, using an introduction from Abel to a Mr. Morley. They quickly established Parkinson’s address for publishers as 1 Hoxton Square in the north of London. Morley suggested Rowntree go there, while Morley pulled all the books by or about Parkinson in their collection.4

Rowntree first inquired at Shoreditch Church, where he enlisted the support of the verger in exchange for two pounds. Rowntree was directed to Hoxton Square while the verger searched the records for the Parkinson family. When he returned, the verger had all of James Parkinson’s biographical details. Rowntree then “secured a picture of the home and of his father’s grave.”4 He included these photographs in his biography.5 The photograph of the house (Figure 1) is the same as that held by the Wellcome Collection.3 Rowntree also captured some of the local Shoreditch life in the photograph.

Rowntree found Parkinson’s house to be vacant and available to rent. He toured the inside and thought the living quarters to be very grand. Another building behind the house, accessible by the side street, appeared to be Parkinson’s medical clinic. Behind that was another building that housed his laboratories and natural history museum. Despite the broken windows, Rowntree was impressed. He found that his father, John Parkinson, had lived and practiced as an apothecary in the house when James was born there in 1755. The house and practice later passed to James. After forty years, he passed it to his son, John, who also lived and worked there and may have passed it on to James’ grandson, the last physician in the line, who died young. James’ great-grandson emigrated to New Zealand in the late nineteenth century. The house became a clothing factory until it was vacated before Rowntree arrived.

When Rowntree returned to the library at the British Museum, he was astounded to see Mr. Morley’s haul of publications and manuscripts by Parkinson and a book by Gideon Mantell on paleontology. He set about reading as quickly as he could, taking notes and quotations. He had more than enough material for his paper to the Johns Hopkins Hospital Historical Society on May 8, 1911, as well as the written version, which was published the following February.

Having dealt with Parkinson’s family life up to his marriage, Rowntree described what he thought was Parkinson’s medical education. He used a publication by Parkinson called The Hospital Pupil to surmise that Parkinson had, in addition to apprenticeship to his apothecary father, sought surgical and medical training from John Hunter, among others. Parkinson believed a firm grounding in Latin and Greek was necessary for students of medicine.

The biography then takes an unexpected turn. Rowntree found several political texts written by Parkinson under the pseudonym Old Hubert. This was the time of the French Revolution and much of Parkinson’s writing was aimed at Edmund Burke. Parkinson took a liberal stance, advocating for causes such as Irish self-rule. Rowntree was astonished to find testimony given by Parkinson before the Privy Council regarding two of his colleagues who had been accused of treason. Rowntree gave a lot of space to this affair. One wonders how he had time to transcribe it, copying machines not being available in those days.

Rowntree then tackles another twist in Parkinson’s career: he had become obsessed with fossils. Mining, for coal in particular, was uncovering strata in the earth containing the remains of animal and vegetable matter. Rowntree gives an overview here, in contrast to the detailed description of his political trials. Like Parkinson, he wrestles with terminology that had not been standardized. In addition, Rowntree describes how Parkinson had to contend with religious dogmatism, which said that fossils were created by the biblical Flood and adhered to a timeline that did not match geological evidence. Parkinson became the foremost author of this new science, publishing three volumes describing and analyzing his findings. Rowntree quotes from Mantell’s A Pictorial Atlas of Fossil Remains to confirm Parkinson’s prominence.

Rowntree next describes Parkinson’s role as a popular scientist, dealing with chemistry in particular. He reviews Parkinson’s popular text The Chemical Pocket-book and describes how Parkinson used the most up-to-date knowledge and argued against old theories such as the antiphlogistic system. Rowntree is also impressed that Parkinson dedicated the final chapter to “animal substances”—what we would call biochemistry—which was Rowntree’s special interest.

We then read about Parkinson’s many contributions to “medicine for the laity.” Rowntree was particularly taken by Parkinson’s approach when writing about children’s health, in which he couched the information in a story for children. He describes Parkinson’s book for healthy living, which advocated for abstinence from alcohol, and he also tells us of the circumstances in which Parkinson wrote a textbook on gout, having suffered the disease and quack cures himself. Rowntree was shown a book by the librarian that had been ascribed to a Dr. Smith, but was actually an attack on Smith’s beliefs written in the style of Parkinson. He also described Parkinson’s Hunterian Reminiscences, a detailed account of John Hunter’s lectures that was published by his son John Parkinson after James’ death. Rowntree’s detailed description of Parkinson’s essay on shaking palsy conforms with all descriptions today and may have been the first time Parkinson’s own words were studied in the century since their publication.

Finally, Rowntree returns to Mantell’s atlas and the author’s introduction, which includes the only contemporaneous description of James Parkinson. Mantell visited him at 1 Hoxton Square and wrote that Parkinson was below average stature but very energetic. He was polite, good humored, and capable of talking on many topics. In trying to sum up Parkinson and why he was forgotten, Rowntree concludes that he did not pursue a few special projects deeply enough. Rowntree may have thought that this was a lesson that he could apply to his own career. Sometime later, Rowntree was amused to learn the National Dictionary of Biographies had used his paper as its source for James Parkinson.

Following a productive decade at Johns Hopkins, Rowntree accepted the chair of medicine at the University of Minnesota. He continued to pursue research and became interested in diabetes insipidus. However, he found the environment insufficiently rich. He was rescued by deployment to France with the American Expeditionary Force. As the assistant to the senior medical officer of the Air Force, he had opportunities to meet senior military and medical figures. He became interested in operational stress, as well as the nascent science of aviation medicine. Upon return, he was recruited to the Mayo Clinic as the clinical head of a research group. He and his group became the most prolific of North American researchers in the 1920s. Suffering exhaustion, he transferred to the Philadelphia Medical Research Institute. Again, he was prolific. In 1940, he was recruited to be the medical head of the US draft. In this role, he frequently briefed President Roosevelt in the company of the war secretary and senior generals.

When Rowntree retired to Florida in 1945, he could look back on a career where he had made seminal contributions to the study of renal failure, liver disease, Addison’s disease, water metabolism, pituitary function, circulation studies, contrast enhanced radiology, and occupational medicine. He received letters around 1955 asking him for the notes and photographic negatives from his biography of Parkinson. They may have been the source for the commemorations of that year and of the photograph in the Wellcome Collection. When he died in 1959, an obituary appeared in JAMA, but he was otherwise forgotten. Like the subject of his biography, he had done too much.

References

- The bicentenary of James Parkinson’s essay on the shaking palsy. Royal Society of Medicine Exhibition. November 2017 – February 2018. Accessed October 21, 2025. https://www.rsm.ac.uk/media/1830/the-little-pamphlet-exhibition-booklet.pdf

- Toodayan N, Lees AJ. Two London Memorials to “James Parkinson [1755-1824], Esq. Surgeon, Late of Hoxton-Square.” Mov Disord. 2025; 40(3): 438-442. doi: 10.1002/mds.30115.

- James Parkinson, No. 1 Hoxton Square. Wellcome Collection. Accessed October 21, 2025. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/mgnzg2g2

- Rowntree LG. Amid Masters of Twentieth Century Medicine. (Springfield IL: Charles C Thomas, 1958), 145-7.

- Rowntree LG. James Parkinson. Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital. 1912; 23: 33-45.

VIVIAN C. MCALISTER is a professor emeritus at Western University Canada, where he is also an adjunct professor in the Department of History. Prior to his clinical retirement, he was a surgeon specialising in transplantation, liver surgery and combat surgery. He spent 11 years in the Canadian Armed Forces, deploying to Afghanistan, Iraq and Haiti.