JMS Pearce

Hull, England, United Kingdom

|

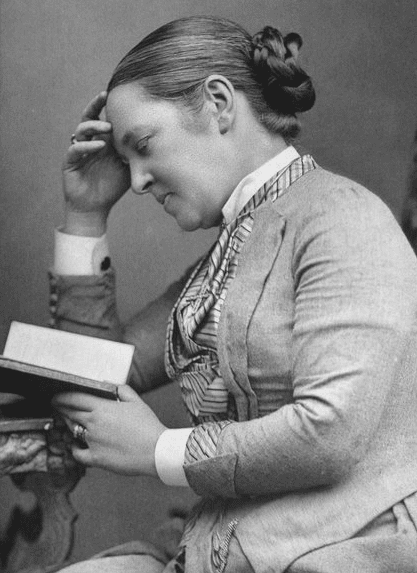

| Fig 1. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Credit: Walery, published by Sampson Low & Co. in February 1889. Via Wikimedia. |

Elizabeth Blackwell and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson were the first women physicians in the United States and Britain.1 Both were born in England. Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-I9I0) was born in Bristol but moved with her family to New York when aged eleven. Only after twelve medical schools rejected her did she manage to enter Geneva College (now Hobart College), a little-known institution in New York State in 1847, graduating MD in 1850. She worked as a midwife in Paris before Sir James Paget helped her to gain entry as a postgraduate into St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, London. She was the first woman to be accepted in a London medical school and the first woman to obtain a place in the English Medical Register, in 1859.2 With help from her sister, Dr. Emily Blackwell, she established the New York Dispensary for Poor Women and Children in 1857.

|

| Fig 2. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital. Photo by SimonNWaddington. 2018. Via Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 4.0. |

Remarkably similar in her struggles against institutional gender opposition and in her eventual achievements in creating hospitals for women, was Elizabeth Garrett (Fig 1). She was born on 9 June 1836 in Whitechapel, London, the elder sister of the well-known suffragist Dame Millicent Fawcett.3 She spent much of her childhood in Aldeburgh, Suffolk. After leaving a Boarding School for Ladies in Blackheath, like Elizabeth Blackwell she found the life of women stultified by a male-dominated society.4 She sought the company of those few women who were making some progress in business or academia. Amongst them was Sarah Emily Davies (1830-1921), with whom she joined the Langham Place Group, a women’s movement in the 1850s. Davies helped to found Girton College for women at Cambridge University; she became Elizabeth’s lifelong supporter.

When Elizabeth Garrett heard that Dr. Blackwell was visiting England, her enlightened father arranged for Elizabeth to meet her and attend her lectures. Though not at first keen on medicine, but encouraged by her father Newson Garrett, a prosperous, entrepreneurial maltster with liberal views, she decided on a medical career, perhaps at first as a protest for women’s rights.

The charters of all medical schools in England specifically forbade the admission of women. In 1860, she joined the Middlesex Hospital as a nurse but inveigled her way to attend medical lectures where possible. But male medical students resented her presence and forced her to leave. Unsuccessful in her attempt to enroll in the medical school, she employed a tutor to study anatomy and physiology until she was allowed into the dissecting room and chemistry lectures. In October 1862, Garrett went to St. Andrews University where Dr. Day, the Regius Professor of Medicine, had invited her to attend his lectures. She worked tirelessly to secure medical training. She was apprenticed to a physician and took further courses of study, finally passing the licentiate examination of the Society of Apothecaries (LSA) in I865—some fifteen years after Blackwell had graduated. A year later, her name was added to the Medical Register (permitting practice in England), Elizabeth Blackwell being the only other woman registered in 1859. In 1870, she gained the MD degree in Paris after viva voce examinations conducted in French.

|

| Fig 3. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson blue plaque. Photo by Spudgun67. Via Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 4.0. |

In 1866, with backing from her father she started the St. Mary’s Dispensary in Seymour Place, where she worked for twenty years. Years after establishing a hospital practice, in 1873 she was admitted to the British Medical Association. A furor followed such that a clause excluding females was added to the articles of the association in 1878, a prohibition not repealed until 1892. Resisting pressures to resign, she remained the only woman member for nineteen years.

In 1874, substantially supported by Dr. Sophia Jex-Blake, Thomas Henry Huxley FRS, and by Elizabeth Blackwell (who had returned to England), she founded the London School of Medicine for Women in Marylebone Road. She became Dean in 1883.5 It subsequently moved to Euston Road and was staffed entirely by women. A year after her death, in 1918 it was renamed Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital on Euston Road (Fig 2) near her home at Upper Berkeley Street. (Fig 3).

She began a happy marriage in 1871 with James George Skelton Anderson of the Orient Steamship Line.6 She combined medicine, marriage, and motherhood with singular success and served as an outstanding model for future women in medicine. They had one son and two daughters; Dr. Louisa Garrett Anderson CBE was a pioneering member of the Women’s Social and Political Union, a suffragette and a surgeon for the Women’s Hospital Corps during the First World War.

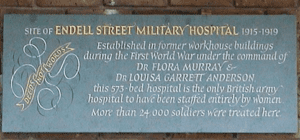

During the First World War, Elizabeth’s daughter Lt. Colonel Louisa Anderson was appointed Chief Surgeon to the 520-bed hospital at Endell Street with her close friend Lt. Colonel Flora Murray as doctor-in-charge. (Fig 4) It was the only army hospital ever to be run and staffed entirely by women. With rigorous discipline they treated over 25,000 injured soldiers with a variety of fractures, amputations, infected wounds, and head and visceral injuries. Their work earned both Anderson and Murray the CBE.7

|

| Fig 4. Endell Street Military Hospital. Memorial Plaque. Image courtesy LondonRemembers.com. |

The Royal Free Hospital moved to Hampstead in 1974; the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital followed in 1983. It finally merged with University College Hospital Medical School in 1998 to form the Royal Free and University College Medical School where there is the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Wing.

Elizabeth’s work at the New Hospital for Women and the London School of Medicine for Women had been limited to the care of women and children; but she also performed surgery and had a successful private practice. She continued as an active but temperate campaigner for women’s equality and was described as “dry, witty and often brusque” with an indomitable will.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson wrote a short textbook, The Student’s Pocket Index, in 1878. Her papers in the British Medical Journal included: Sex in Education (1892), The History of a Movement (1893), and Medical Education of Women: The Qualification of Female Practitioners (1895), Deaths in Childbirth (1898), and What is Efficient Revaccination? (1901).

She retired to Aldeburgh in 1902 and was elected there as first female mayor in England in 1908. (Her father had been mayor in 1889.) She died on 17 December 1917 at Aldeburgh.

Louisa, her daughter, wrote:

“In her girlhood, Elizabeth heard the call to live and work, and before the evening star lit her to rest she had helped to tear down one after another the barriers which, since the beginning of history, hindered women from work and progress and light and service.”5

Her legacy is that today over half of the medical students in Britain are women.

References

- Roth N. The Personalities Of Two Pioneer Medical Women: Elizabeth Blackwell And Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. Bull NY Acad Med1971;47:67-79.

- Pearce JMS. Elizabeth Blackwell, MD. Hektoen International Winter 2016.

- Manton, Jo. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. New York: Dutton, 1965.

- Brook, B., Elizabeth Garrett Anderson: ‘A Thoroughly Ordinary Woman’, Aldeburgh, Suffolk, 1997.

- Obituary. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson MD. British Medical Journal 1917;2:844-6.

- Garrett Anderson, Louisa. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, 1836–1917. London: Faber & Faber, 1939.

- Cooper A. The Endell Street Military Hospital. Hektoen International. Winter 2015.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of science and medicine.

Fall 2021 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply