Jayant Radhakrishnan

Nathaniel Koo

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

|

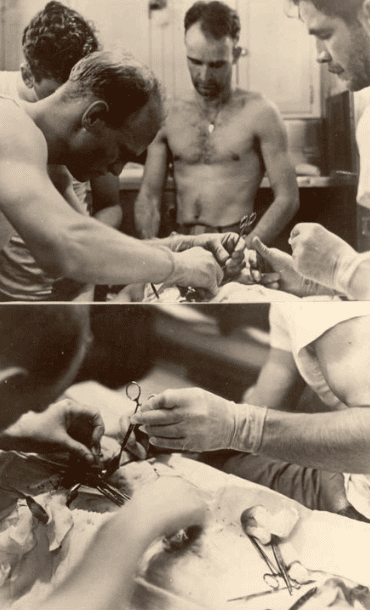

The Silversides Appendectomy was photographed by XO Roy Davenport, at the patient’s head. Thomas Moore is the dark-haired bearded man in the T-shirt. From the USS Flier Project. |

Appendectomies are routine procedures—until they are not. Three cases of auto-surgery and three other semi-pro appendectomies are worth revisiting.

Evan O’Neill Kane (1861-1932) was a well-regarded surgeon who gave an exceptionally detailed account of his auto-appendectomy on February 15, 1921.1 While waiting in the operating room for the surgical team to start the procedure, he had the bright idea to carry out his own appendectomy, supposedly to demonstrate it could be done under local anesthesia. Since he was the chief surgeon at his family’s Kane Summit Hospital in Kane, Pennsylvania, the staff had no option but to go along with his whim. He propped himself up on the bed with pillows and had the nurse anesthetist push his head well forward. After injecting the local anesthetic into the skin and abdominal wall, he rapidly entered the abdomen, found and removed the appendix, and had his assistants close the wound. The operation was done within thirty minutes. During the procedure he unintentionally tightened his abdominal muscles to draw himself up straight when turning in the appendicular stump, resulting in a few knuckles of intestines spilling out of the incision. They were easily replaced in the abdomen. He claimed that he could have completed the operation faster if his staff had not been so nervous and unsure of what they were supposed to do.2 This was not Dr. Kane’s first foray into self-surgery for he had amputated one of his fingers two years earlier, nor was it his last, as he repaired his own inguinal hernia in 1932 with the press and a photographer in attendance. During the herniorrhaphy he became too drowsy to suture the wound closed so Howard Cleveland, who succeeded him as chief surgeon, had to finish the job. Kane died a few months later after giving evidence in favor of his son who was tried and acquitted of killing his wife.

Leonid Ivanovich Rogozov (1934-2000) had one year of surgical training when he sailed with the 6th Soviet Antarctic expedition on November 5, 1960, to be the sole doctor at Novolazarevskaya Station. While in Antarctica, on April 29, 1961, he felt right-sided lower abdominal pain, which he diagnosed as appendicitis. He placed himself on non-operative management but the disease progressed and he developed signs of localized peritonitis by the next day. Since there was no way for him to travel the 1,000 miles to Mirny, the nearest Soviet research station for medical care, it soon became obvious to him that his choices were to operate upon himself or to die. Fortunately for us, he recorded his thoughts and feelings in great detail in a log. Some excerpts from the preoperative notes are: “I did not sleep at all last night. It hurts like the devil!” and “. . . I have to think through the only possible way out: to operate on myself . . . It’s almost impossible . . . but I can’t just fold my arms and give up.” Once Rogozov decided on the course of action and the base commander obtained permission from Moscow, the operation commenced at 2 AM on May 1st. Rogozov had made immaculate plans for every contingency and communicated them to the assistants he had recruited. He assigned specific roles to two main assistants, one to direct the light and hold up the mirror and the other to hand him the instruments. He even had the station director positioned in the room as a backup, in case either one of the assistants passed out. Finally, he taught them how to administer epinephrine and to ventilate him if he passed out. As soon as he started the operation, he realized the difficulty of working with a reversed image so he dispensed with the mirror and decided to operate by touch. To enhance the feeling in his fingers he chose not to wear gloves. Positioning himself in the semi sitting position with the right hip slightly elevated, he injected the local anesthetic and then made the incision. He injured the cecum when incising the peritoneum so he had to repair it before continuing with the operation. He best explains the sequence of events: “suddenly it flashed through my mind: there are more injuries here and I didn’t notice them . . . I grow weaker and weaker; my head starts to spin. Every 4-5 minutes I rest for 20-25 seconds. Finally, here it is, the cursed appendage! With horror I notice the dark stain at its base. That means just a day longer and it would have burst and . . .” By 4 AM the appendix was removed and the abdomen closed but he made certain that the assistants cleaned the instruments and tidied up the room before he let them leave. He then took an antibiotic and sleeping pill and rested. His recovery was uneventful and he was back at work in two weeks.3 He returned home a hero on May 29, 1962, completed his studies, and then practiced in Leningrad (St. Petersburg) until he died of lung cancer at sixty-six years of age.

Robert Kerr “Jock” McLaren (1902-1956) was born in Scotland and fought with the British Army in World War I. He moved to Queensland, Australia, after the war and worked as a veterinary officer in Bundaberg. At the onset of World War II, he joined the Australian Imperial Force and went to fight in British Malaya. When Britain surrendered in 1942, he was captured and imprisoned by the Japanese in the infamous Changi prison in Singapore. He broke out and proceeded to fight alongside the local guerillas until he was recaptured. This time, he was incarcerated in a high security camp in Borneo. He escaped again and made his way to Mindanao in the Philippines. However, his trials were not yet over as he developed appendicitis, and with the Japanese on his tail there were no prospects of him getting medical care. Fortunately for him, a Moro chieftain and his wife risked their lives and took him in. They summoned a Filipino medical student to operate on him. The student at first refused but eventually he reluctantly agreed to assist after McLaren wrote out and signed his own death certificate. His hosts used floorboards to make an operating table and tore up sheets for bandages. McLaren had two large dessert spoons bent to function as retractors. He had the spoons sterilized by boiling in a rice pot along with a razor blade, a pair of scissors, forceps, and a needle. He then positioned himself on the table with a mirror directed so he could see the proposed incision site. He made the skin incision without benefit of any anesthetic and “prised the muscles apart as he had often done in operating on horses and cows and inserted the spoons to hold them in place.” An old midwife held the “retractors” in place while the “white and sweat beaded” medical student passed him the instruments. He found, amputated, and withdrew the appendix out of the wound. It was only when he started sewing the wound shut with banana leaf fiber that he felt excruciating pain with each stitch. The operation took four and a half hours. Two days later, he was up and running from the Japanese again. He attributed his prompt recovery to having spread and not cut the muscles.4 There was a huge bounty on his head but he was not captured again. Pinkerton jokes that it was “possibly because everyone was terrified of the notorious rebel leader known to leave severed appendixes in his wake.”5 In fact, he took the jar containing the appendix when he fled from Mindanao and its fate is unknown. In 1948 when reporters asked him about the experience, he said, “It was hell but I came through it all right.” McLaren died on March 3, 1956 when he backed his jeep into a pergola and was hit by falling timber.

Kane’s and Rogozov’s operations were witnessed, recorded, and photographed. Unfortunately, there is no eyewitness report or photographic confirmation of McLaren’s operation or his abdominal scar.

Space restrictions on American submarines do not leave room for an operating room or even an extra person such as a doctor. However, in the last four months of 1942, three documented appendectomies were carried out on submarines at sea. The first one received the most publicity. On September 11, 1942, Pharmacist’s Mate 1st class Wheeler Bryson Lipes, (1920-2005) operated upon Seaman 1st class Darrel Dean Rector while the USS Seadragon (SS 194) was cruising in enemy waters.6 Spoons were used as retractors, and he dripped ether on a gauze-covered inverted tea strainer to anesthetize the patient. The makeshift instruments were sterilized in boiling water and torpedo alcohol. The latter was also used to preserve the excised appendix. Credit for the second appendectomy goes to Pharmacist’s Mate 1st class Harry B. Roby on the USS Grayback (SS-208). On December 14, 1942, he operated on Torpedoman’s Mate 1st class WR Jones. The third appendectomy was performed by Pharmacist’s Mate 1st class Thomas A. Moore on Fireman 3rd class George M. Platter while the USS Silversides (SS-236) was at sea on December 22, 1942. All three patients recovered uneventfully and all the pharmacist’s mates were duly promoted. However, the filthy conditions on a submarine, absence of surgical instruments, and the fact that pharmacist’s mates were not trained to perform abdominal operations must have alarmed the brass. No further appendectomies were done for the rest of the war aboard submarines, although there was no official notification to that effect. In the Science News Letter of January 22, 1944, submariners were advised to use sulfa drugs for appendicitis.7 Since then, submariners have always been treated with antibiotics until the ship can surface safely for the sailor to be transferred for further care. This regimen was particularly useful during the Cold War if the submarine happened to be in unfriendly waters when the sailor fell ill.

Hippocrates (circa 460-circa 370 BCE) was right: “For extreme diseases, extreme methods of cure, as to restriction, are most suitable.”

Bibliography

- Kane EO (1921): Autoappendectomy.(A case history). Internat J Surg 34(3):100-102.

- Nwaogbe C, Simonds EA, D’Antoni AV, Tubbs RS (2018): Surgeons performing self surgery: A review from around the world. Translational Research in Anatomy 10:1-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tria.2017.11.001.

- Rogozov V; Bermel (2009): Auto-appendectomy in the Antarctic: case report. BMJ. 339: b4965. doi:10.1136/bmj.b4965. PMID 20008968. S2CID 12503748.

- Gilling T (2021): Jock McLaren, Australia’s ‘cloak and dagger’ war hero. The Weekend Australian magazine January 29, 2021.

- Pinkerton P (2015): Robert McLaren removed his own appendix in the jungle. Outdoor revival October 12, 2015.

- Schneller RJ (2004): PhM1/c Wheeler B. Lipes and a Submerged Appendectomy. Naval History and Heritage Command, Naval Historical Center September 2004.

- Chesser PJ: Appendectomies on Submarines During World War II – USS …https://usssabalo.org › T-AppendectomyWWII.

JAYANT RADHAKRISHNAN, MB, BS, MS (Surg), FACS, FAAP, completed a Pediatric Urology Fellowship at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston following a Surgery Residency and Fellowship in Pediatric Surgery at the Cook County Hospital. He returned to the County Hospital and worked as an attending pediatric surgeon and served as the Chief of Pediatric Urology. Later he worked at the University of Illinois, Chicago from where he retired as Professor of Surgery & Urology, and the Chief of Pediatric Surgery & Pediatric Urology. He has been an Emeritus Professor of Surgery and Urology at the University of Illinois since 2000.

NATHANIEL C. KOO, MD, FAAP, is an Assistant Professor of Surgery and Associate Program Director of the General Surgery residency at the University of Illinois, Chicago. He obtained his medical degree and general surgery training at the University of Illinois, College of Medicine, Chicago. Then he did two years of research at Northwestern University and he completed a two year Pediatric Surgery Fellowship at Lurie Children’s Hospital, Chicago before returning to his alma mater.

Leave a Reply