| ART AND MEDICINE IN FLORENCE |

| Published in October, 2020 |

| H E K T O R A M A |

| . |

|

Artists, statesmen, scholars, warriors, and even popes were affected by syphilis in those times. Take King Francis I of France (1494–1547). A polished man, patron of the arts, lover of knightly romances, epicurean, sensual, amiable, and an incorrigible womanizer, his compatriots have idealized him as the epitome of refined French galanterie and Gallic power of seduction. A tradition says that one day, when the king enjoyed a pleasure outing in one of the many fairyland castles that he owned in the placid countryside of La Douce France, a burning torch came loose from the brackets that held it on the wall, fell on his head, and burned his scalp. Since then, according to this story, the monarch always covered his head with a big beret; hardly ever was he seen without it. This, in fact, is how we see him in the portraits that Titian and Jean painted of him (Figure 1).

|

| GHIRLANDAIO, HUMANISM, AND THE TRUTH: THE PORTRAIT OF AN ELDERLY MAN AND YOUNG BOY | |||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|||||||

| THE BONIFACIO HOSPITAL: REFORMING PSYCHIATRIC HOSPITAL CARE | ||||

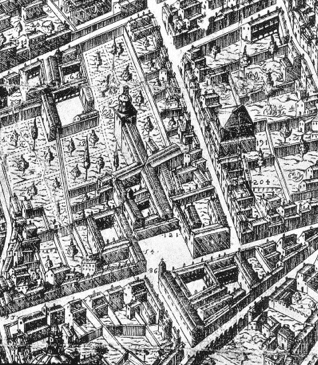

In 1369-1377 Bonifacio Lupi, mayor of Florence and Captain of the People, founded the Bonifacio Hospital (Ospedale di Bonifacio) dedicated to St. John the Baptist. In the sixteenth century, the hospital admitted patients suffering from syphilis, known as the “French disease,” spread by troops of Charles VII returning from Naples. Later the Grand Duke Gian Gastone de “Medici” (1671-1737) restricted admission to the hospital to the disabled poor and elderly; and in 1774 the Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo turned it into a hospital for mentally-ill patients. He was a young man of the Enlightenment, a social and economic reformer, and his reforms included the rehabilitation of juvenile delinquents, the abolition of the death penalty, smallpox inoculation, and the humane treatment of the mentally ill. Leopoldo’s 1774 “Law on the Insane” constituted the first legal statue in Europe that ensured institutional care for the mentally impaired, and he reconstructed a wing of the Bonifacio Hospital for that purpose.1The first mentally-ill patients were admitted in 1788; some were transferred from other hospitals in the surrounding areas of Florence. To lead the hospital, Leopoldo chose the young physician Vincenzo Chiarugi (1759-1820), who had studied medicine in Pisa and later had worked at the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence.

|

||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

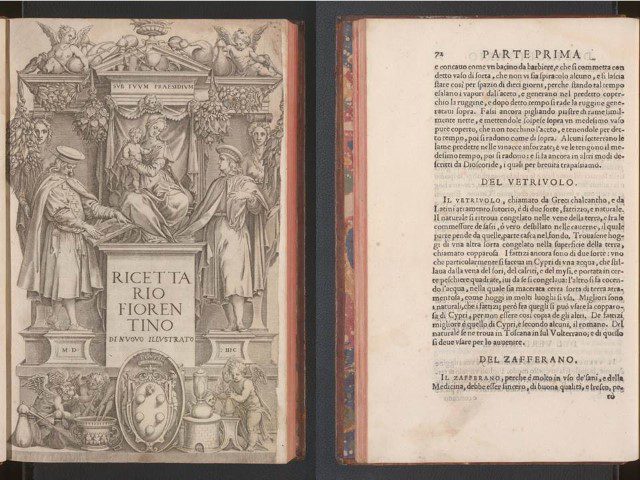

| THE FLORENTINE RENAISSANCE APOTHECARY | ||||

The apothecaries had at their disposal pharmacopeias and art-related treatises delineating recipes for medicinals and pigments, respectively. Artists in their individual workshops developed recipes for preparing pigments using organic, mainly plant-based, and inorganic materials, e.g. minerals, byproducts of glass making, and others. A major codification of those preparation techniques was published by the Tuscan painter, Cennino Cennini, near the end of the fourteenth century or the beginning of the fifteenth century. His treatise, Il Libro dell’Arte, is a valuable compendium that also contains discussions of artistic techniques.5 After purchasing pigments from apothecaries, artists prepared them with a medium to produce the consistency of paint desired. For both apothecary and artist, knowledge of the ingredients and of the parameters involved in timing and level of grinding were crucial.

|

||||

| PIERO DI COSIMO | |||||

. . . when eighty years old, he became so strange and eccentric that he was unbearable. . . . He would not allow his apprentices to be about him, so that he obtained less and less assistance by his uncouthness. . . . The flies annoyed him, and he hated the dark. . . . He abused physicians and apothecaries, saying that they made their patients die of hunger, in addition to tormenting them with syrups, medicines, clysters and other tortures, such as not allowing them to sleep when drowsy . . . and thus he went on with these most extraordinary notions, twisting things to the strangest imaginable meanings. . . . After such a curious life he was found dead one morning at the foot of the stairs, in 1521

|

|||||

| DOCTORS AND ILLNESS IN BOCCACCIO DECAMERON | ||||

Giovanni Boccaccio was born in Tuscany in 1313, the illegitimate son of a merchant of Certaldo, who launched him on a commercial career hoping he would follow in his steps. Sent to Naples for that reason, he soon abandoned commerce and the study of canon law, and began instead to write stories in verse and prose. He mingled in courtly society, and his house became a center of literary activity. During this period he formed a lasting friendship with Francesco Petrarch, who introduced him to the world of classic authors. At the time, not only Petrarca, but many others of the intellectual establishment, looked up to the Greeks & Roman writers, poets, and thinkers. They thought that the Greeks (Aristotle in particular) had gone further in logic, philosophy, and science than they had themselves. This kind of conversion was considered a beacon of renewal and progress, in contrast to the still dominant medieval spirit.

|

||||

Leave a Reply