John Raffensperger

Fort Meyers, Florida, United States

|

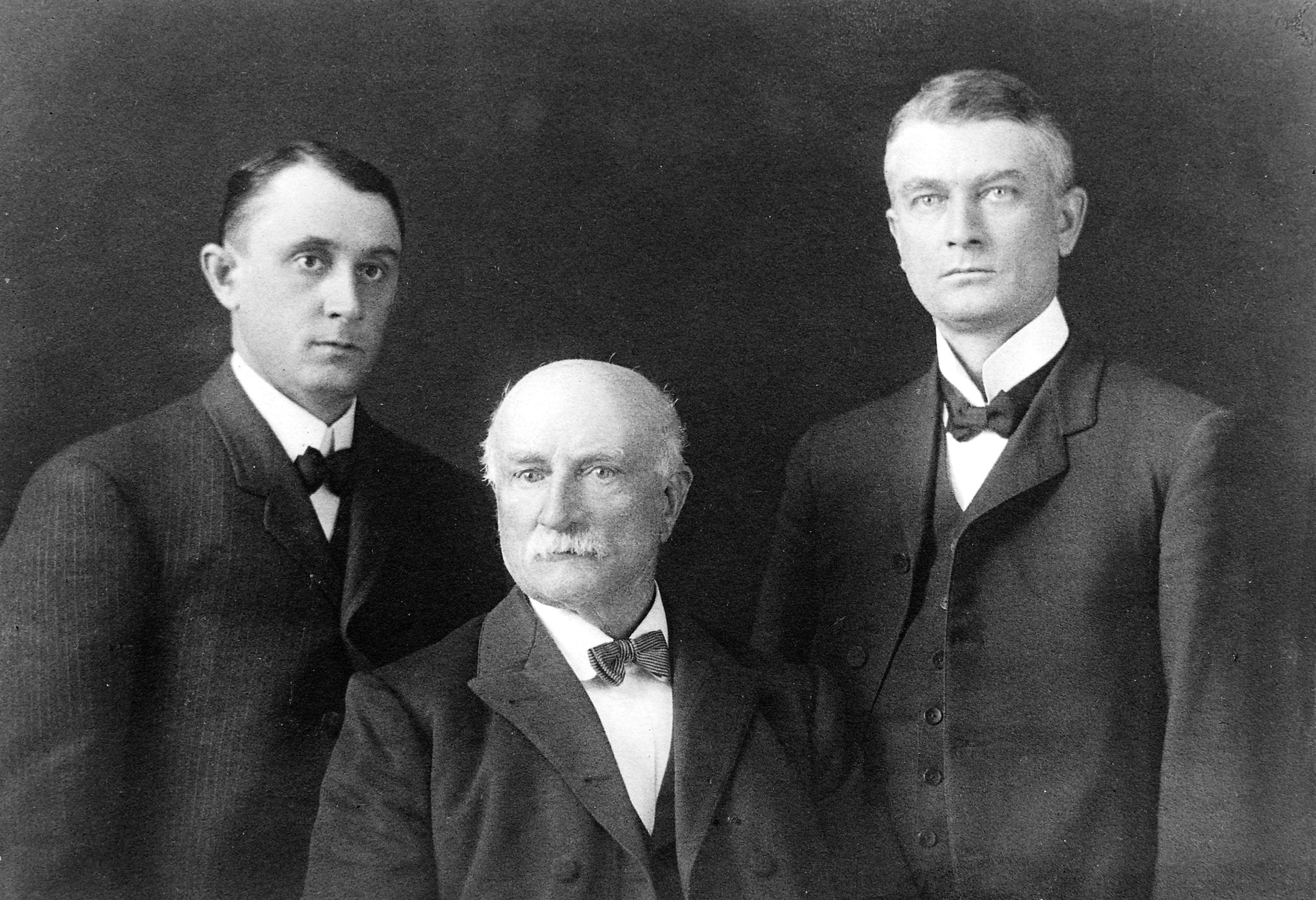

| Portrait of William Worrell Mayo and his sons: Charles Mayo (right) and William James Mayo (left). Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) |

The father of the Mayo brothers, William Worall Mayo, was born in a village near Manchester, England, in 1819. His father died when he was seven years old, but his mother managed to have him tutored in Latin and Greek, and later he took private lessons with James Dalton, a chemist best known for developing the atomic theory. He then studied medicine.

At the age of twenty-six years he traveled to America and briefly worked as a chemist at Belleview Hospital in New York. In 1849, he apprenticed to a doctor in Indiana and then took a one-year course at the Indiana Medical College in La Porte, Indiana. He earned an MD and set out for the Minnesota territory with his new wife. He traveled about the territory, tried his hand at various enterprises, and was involved in one of the last Indian skirmishes.

In 1864, he developed a medical practice in Rochester, a small town in southern Minnesota. Rochester was the center for a large agricultural area and was on the railroad that connected Chicago with the West. Dr. Mayo’s first surgical work was in repairing injuries from farm machinery. He also took an interest in gynecological problems and visited hospitals in the East to observe the removal of ovarian tumors.

William James Mayo was born in 1861 and Charles Horace four years later. They spent long hours together playing, fishing, hunting, and doing the chores. Charlie was more serious and studious and had an aptitude for anything mechanical. When they were teenagers, Charlie put together a steam engine to run the well pump and turn wheels to do the family washing. Will was an average student and was a bit withdrawn. They attended the local high school and had private lessons in German, French, and Latin. They picked up from their father chemistry and physics and a love of reading. They did farm work and Charlie had a job at the local drugstore. The boys went on house calls with their father and watched as he diagnosed and treated his patients. They also assisted at surgery and autopsies. Charlie even gave anesthesia. The boys learned medical ethics from their father and did not charge patients who could not afford to pay.

In 1880, Will entered the University of Michigan Medical School’s four-year course with science and bedside teaching in the University Hospital. During his senior year, the chief of surgery, Dr. Donald Maclean, chose Will to be his assistant. Dr. Maclean was one of the first American surgeons to take up Lister’s antiseptic surgery. After graduation, Dr. Will went back to Rochester to practice with his father. Charlie went to the Chicago Medical School, which was affiliated with Northwestern University. He was an average student, but managed to spend a good deal of time observing Nicholas Senn, Christian Fenger, and other Chicago surgeons. In 1888, he finished a three-year course and joined his father and brother in practice.

The Mayo father and sons delivered babies, treated measles, whooping cough, diphtheria, and all the ailments seen in a general practice. They rode horseback through floods and washed-out roads, and when the snow was too deep for a horse, they walked to their patients in the country. At first, their surgery was limited to repairing accidental wounds, but during the decade of the 1880s the elder Mayo performed thirty-six operations to remove ovarian tumors. Their surgical practice increased as news of their success spread by word of mouth and newspaper stories. Doctors in the surrounding area often watched the operations and, impressed with the skill of the Mayo family, referred more cases to them.

From the beginning of their practice, the brothers set aside time to study and travel to observe the work of other surgeons. They took turns traveling to Chicago on the night train to attend Christian Fenger’s clinics at the Cook County Hospital and to observe surgeons such as Nicholas Senn and John B. Murphy. Fenger, an immigrant from Denmark and the “Father of surgery in Chicago” was more interested in pathology than in the patient. On one visit to Chicago, Dr. Charlie and his father observed John B. Murphy perform an intestinal anastomosis with his invention, the “Murphy button.” This device allowed surgeons to make quick, safe connections between the stomach or gallbladder with the intestine. It literally opened the door to surgery of the gastrointestinal tract. Soon after their return to Rochester, the brothers used the button to save the life of a patient. On trips to New York and to Germany, they learned Lister’s antiseptic and later aseptic technique. At Johns Hopkins, they were impressed with William Halsted’s slow, meticulous operations for hernia and breast cancer. They learned surgery by taking the best of what they saw. Back home, they operated in the patient’s home, often on a kitchen table or on planks across sawhorses.

In 1883, a tornado demolished Rochester and caused multiple injuries. The doctors turned a dance hall into an improvised hospital and Sisters from the St. Francis convent took over the nursing. This led to the founding of St. Mary’s Hospital. The Mayos planned and supervised the construction of the forty-five bed hospital with one operating room. It was open to all patients regardless of their ability to pay. At first Protestants objected to a Catholic hospital, and money to equip the hospital was in short supply. The Mayos equipped the operating room and Dr. Charlie built the operating table. The nursing sisters worked long hours to care for the patients and did all the marketing for food and supplies. By 1893, the hospital was caring for a thousand patients a year and was a great success, due in equal measure to the nursing sisters and the Doctors Mayo.

During the early years, the brothers assisted one another and each did all sorts of operations. As a result of their study and travel they took up the great advances in surgery during the last decade of the nineteenth century. They obtained a sterilizer for instruments, used rubber gloves, and performed all the latest operations. Dr. Will did more of the pelvic and abdominal operations while Dr. Charlie took over the eye, ear, nose, and throat work and eventually did orthopedics and brain operations.

There was a tremendous backlog of patients suffering with chronic gastro-intestinal pain, “dyspepsia,” and “colic.” Reginald Fitz, a Harvard pathologist, recognized the appendix as the source of pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen. Soon surgeons, including the Mayos, advocated appendectomy for right lower quadrant abdominal pain. In 1895, they performed twelve operations on the appendix. These numbers grew rapidly in the ensuing years. Next was the removal of gallstones for recurrent episodes of “colic” and operations for inguinal hernia. In 1894, Dr. Will commenced doing gastroenterostomy with the Murphy button for pyloric obstruction. This led to complete removal of the stomach for cancer. By 1905, the Mayos had performed 2,157 abdominal operations at the St. Mary’s Hospital. Meanwhile, Dr. Charlie was doing tonsillectomies, excising knee joints, removing breast cancers, and developed an operation for varicose veins.

At first their surgical practice was limited to Rochester and the immediate area, but as their fame grew patients poured in from throughout the Midwest. Part of this influx of patients was because of the appointment of the old Dr. Mayo as surgeon for the Chicago and Northwestern Railway. Whenever a train derailed with multiple injured passengers or when a patient developed appendicitis in a distant town, the railroad arranged special fast trains for the doctors. This led to considerable favorable publicity and more patients.

By 1905, the old doctor, W.W. Mayo, spent more time in politics and farming than medicine. The brothers could not keep up with their growing surgical practice and still see office patients. They hired experienced physicians to help with the diagnostic work. When Dr. Charlie married their nurse anesthetist, they hired a Chicago-trained nurse to give anesthesia and then took on Dr. Christopher Graham, her brother, who did obstetrics and laboratory work. They recruited doctors who specialized in urology and optometry.

The most important addition to the staff was Henry Plummer, a graduate of Northwestern University, who had spent several summers working at St. Mary’s Hospital. Dr. Plummer took over the clinical laboratory work and X-ray. He was also a superb clinician, with a special interest in diseases of the thyroid. Dr. Plummer, an eccentric but brilliant doctor, also designed new clinic buildings and organized research laboratories.

During the early years, the brothers had assisted one another at surgery, but with the increased workload, they had separate schedules. Sister Joseph, a highly intelligent nurse with “nimble fingers” became Dr. Will’s first assistant. In later years, residents assisted the brothers and often “opened and closed,” but the brothers did the essential part of the operation.

The Mayos had regularly discussed papers at medical meetings and as their personal experience grew, they presented their own work on appendicitis, gallstones, and stomach surgery. In 1904, they reported their results of one thousand operations on the gallbladder, and in 1905, at the American Surgical Association, Dr. Will reported on 500 cases of gastroenterostomy. Surgeons in academic centers were astonished and doubtful about the numbers of cases and the excellent results. The brothers invited the skeptics to visit Rochester and see for themselves. Surgeons came to Rochester to see the Mayo brothers at work. They came first from the United States and then from all over the world and marveled at the volume and excellence of the surgery they witnessed.

The increased number of patients required expansion of the hospital, the clinic, the laboratories, and the addition of more doctors. The Mayo Clinic was born with the opening of a new building in 1914 with offices for the doctors, laboratories, a business office, and a new filing system. The brothers envisioned and brought about the concept of a private group practice of closely integrated specialists. The next step was the Mayo Foundation for the education of residents and research.

Rochester was in the “goiter belt” and so the Mayos treated many patients with simple goiter, but until the 1920s, patients with exophthalmic goiter were a major challenge. These patients suffered weight loss, severe tachycardia, restlessness, and many died. There was no good medical treatment and surgery often resulted in “thyroid storm” with an uncontrolled rapid heart rate, coma, and often death. Iodine was used to treat simple goiter and Dr. Henry Plummer and his research associates isolated thyroid extract to treat hypothyroidism. After considerable study, Dr. Plummer tried iodine in patients with exophthalmic goiter. Patients immediately improved and with pre-operative iodine surgeons were able to do thyroidectomies with less than a one percent mortality. This remarkable feat typified the cooperation of clinicians and researchers that exemplified the teamwork of the Mayo Clinic.

The brothers continued to operate three days a week and saw patients in the clinic in the afternoon. They attended the weekly staff meetings and continued to maintain the same humanitarian principles of patient care as their father.

In 1928, a new fifteen-story clinic building opened and that same year, at age sixty-seven, Dr. Will did his last operation. Dr. Charlie retired a year and a half later after he had a retinal hemorrhage. Dr. Charlie died of pneumonia in the spring of 1939 and Dr. Will passed away two months later with stomach cancer.*

During their lifetime the Mayo brothers were honored by foreign countries and medical societies all over the world. They were the presidents of the American College of Surgeons and almost every other major medical society in the United States. They published over six hundred medical papers and trained countless young surgeons. Today every operating room has a Mayo table for instruments, a Mayo retractor, and the Mayo scissors. The clinic, which they planned, organized, and often funded out of their own pockets, is known throughout the world as an oasis of excellent medical care. Their concept of a not-for-profit, non-governmental integrated group practice could well be a model for health care today.

- The material in this article was abstracted from “The Doctors Mayo” by Helen Clapesattle, published by the University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis; second edition, condensed, 1954

JOHN RAFFENSPERGER, MD, first heard of the Mayos at age ten years, during the 1930s, when the family doctor referred friends and relatives to the clinic. The Mayo brothers, perhaps more than any others, advanced surgery during the first half of the 20th century. The clinic continues to be a center of medical excellence and a model for future health care reform. Dr. Raffensperger graduated from the University of Illinois College of medicine in 1953, trained in surgery at the Cook County Hospital, and became a pediatric surgeon. After retiring, he trained a hunting dog, taught sailing on Lake Michigan, wrote medical history, and has tried his hand at writing fiction.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 1 – Winter 2021

Leave a Reply