Travis Kirkwood

Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

|

|

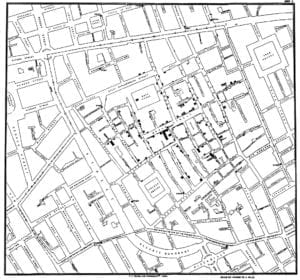

Original map made by John Snow in 1854. Cholera cases are highlighted in black. 2nd Ed by John Snow. Public Domain due to age. |

John Snow is often referred to as the father of modern epidemiology. His work is certainly worthy of this1 and present-day public health2 still strives toward upstream approaches, primordial prevention, and redress on the social determinants of health. It seems however that the core lessons from John Snow back in 1854 have yet to be adequately integrated into public health policy and practice.

Before any scientific knowledge of the existence of pathogenic microorganisms, Snow identified the source of a cholera outbreak afflicting inhabitants of Soho, London in 1854. Snow associated the contamination of human drinking water—particularly via human feces—with the frequency of cholera disease. This association that Snow proposed carried an attendant solution to the epidemic, which proved to be swift and effective: the Broad Street pump was shut off. 3

There was no burst of superhuman insight required on the part of Snow. Rather, he patiently employed a healthy admixture of empiricism, critical thinking, hypothesizing, and eventually a dot map to prove the merit of taking a literal upstream approach in combatting infectious disease. He did this at a time when to even posit the existence of something like Vibrio cholerae4 might draw scorn and ridicule. To the unaided human eye, and without all the benefits of modern knowledge, the rapid diminishment of disease that followed the efforts of John Snow and his contemporary public health pioneers seemed miraculous. The real change, of course, is attributable to the fact that large numbers of people ceased to regularly ingest human feces.

The fundamental lesson in the story of John Snow is that it can be highly effective, and certainly more efficient, to address the root causes of human suffering and disease.5 Because although there are many ways in which the water supplying the Broad Street pump may have been filtered and treated, and although there are many ways that those people ingesting the water may have been treated clinically, it would seem futile to pursue any of these measures; rather, an “upstream” solution would be to ensure that fewer people defecate directly into drinking water supplies.

In many ways this should be staggeringly obvious. To take an upstream approach to public health and to public policy more generally, is to simply start at the start. Cholera is a disease of poverty. This is also true of tuberculosis and rheumatic fever, which are two more examples of diseases that prevail today in contexts of unjust deprivation; where basic necessities are not being met. From an activist perspective, cholera is a symptom of injustice and neglect.

To be fair, this all depends on our chosen level of analysis. The human experience is complex. When there are many causes at play, it can be futile to focus on just one. Rather, we can focus on those fundamental determinants of health that are correlated with other downstream factors that we deem to be important. This is why we treat drinking water before consumption, without knowing exactly which health issues have been mitigated in doing so.

This is to say that, depending on our chosen level of analysis, poverty is irrefutably a mechanism for disease transmission and acquisition that is equal in importance to the more minute and direct mechanisms by which Vibrio cholerae has its effects. The only difference is whether we approach the issue from the perspective of a biomedical professional rather than that of a civil engineer, sociologist, economist, or a public health professional with “big picture” motivations. Since all microorganisms need a reservoir or a host environment, focusing solely on microorganisms themselves is myopic and ill-advised.

Literature on the social determinants of health demonstrates that there any many factors beyond the direct purview of biomedical practitioners, but which nonetheless cause, contribute to, or compound human health complications. These factors include, but are not limited to:

- Overcrowded, moldy, and inadequate housing and homelessness

- Malnutrition, undernutrition, and their attendant effects

- Stressors such as relative poverty, which are ultimately biopsychosocial phenomena

- Contaminated air, soil, water supplies, etc.

- Lack of access to quality health services including medicines and vaccines

In the World Health Organization’s World Health Statistics 20188 report, section 3.2 titled Cholera—An Underreported Threat to Progress states:

“. . . cholera is a stark indicator of inequality and lack of social and economic development as it disproportionately affects the world’s poorest and most vulnerable populations . . . Cholera transmission is closely linked to inadequate access to clean water and sanitation facilities . . . most of the counties that reported locally transmitted cholera cases to WHO during the period 2011-2015 were those in which only a low proportion of the population had access to basic drinking water and sanitation services . . .” (pp. 16).

Although detailed biomedical knowledge and technologies have advanced tremendously since the nineteenth century, optimal solutions remain largely unchanged. It remains true that addressing human suffering one issue at a time for diseases such as cholera is inefficient and not justified by the available evidence. When it comes to budgeting, spending, policy, and practice, emphasis on individual illnesses is reactive, superficial, symptoms-based, inefficient, and defensive of the status quo. It is lazy and morally indefensible to not address the high prevalence and incidence of infectious diseases at their most fundamental sources; infrastructure for adequate housing, hygiene, and nutrition is the obvious place to start.

Cost is no excuse, especially given the astronomical levels of debt that rich nations such as Canada and the United States continue to accrue. Meanwhile, the cost of inaction is similarly astronomical, and mounting. Productivity is lost when people starve or are incapacitated by preventable disease. With a little bit of forethought, the return on investment from doing the right thing is ours for the taking. Vaccines and antibiotics are critical, but less fundamental than basic human needs.

End notes

- See: a) any introductory Epidemiology textbook; b) The Strange Case of the Broad Street Pump [Book] by Sandra Hempel 2007; c) The Ghost Map: The Story of London’s Most Terrifying Epidemic—and How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World [Book] by Steven Johnson (2007). Also, as the title of Steven Johnson’s book would suggest, it can be argued that the very concept of Public Health and its fundamentals originate from John Snow’s work.

- This is most strongly in reference to public health and epidemiological scholarship; textbooks such as Dennis Raphael’s The Social Determinants of Health: Canadian Perspectives (2016), and scientific articles as might be found in the Annual Review of Public Health. However, it is also increasingly common to hear from the mouths of those working in public health policy and practice; in government; and it is abundant in reports and strategic planning documents, etc. It is also common in medical school (and other care provider) curricula, and amongst healthcare workers and management more broadly. Notwithstanding the commonness of this ‘holistic’ and ‘upstream’ language, commitment in action and funding misses the mark quite dramatically. So, this is a big and difficult subject to summon so cursorily, but it may have been more accurate to say “present-day public health still gives the appearance of striving incessantly towards ‘upstream approaches…”

- The finer details of John Snow’s medical detective work are fascinating. Although the cholera epidemic may have been waning prior to the broad street pump handle being removed, John Snow’s efforts were nonetheless genius, and admirable to the point of heroism.

- This is the name of a species of bacteria. Certain strains belonging to Vibrio cholerae are the cause of cholera disease.

- This is especially true in light of the horrifically harmful medical practices and medicines that were common throughout the 19th and much of the 20th century. The above-referenced book The Ghost Map also describes these practices and medicines with some detail.

- A disease of society: cholera through the ages (2013), by Khameer Kishore Kidia. Published by Hektoen International. Article to be found at: https://hekint.org/2017/02/01/a-disease-of-society-cholera-through-the-ages/?highlight=cholera

- Very simply, miasma theory posits that all disease is caused by ‘bad smells’ and dirty air. Skimming though Wikipedia’s “Miasma theory” page will suffice: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miasma_theory

- World Health Statistics 2018: Monitoring health for the SDGs, available online at: https://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2018/en/

TRAVIS J. KIRKWOOD, BSC, MPH, is an Analyst with the Assembly of First Nations (AFN).

Winter 2020 | Sections | Infectious Diseases

Leave a Reply