Paula Carter

Chicago, Illinois

Lucy Reyburn Rittgers and two of her daughters, circa 1948. Source: Family photo

In 1924, Lucy Reyburn gave birth to her first child, a daughter she named Darlene. Lucy lived in Iowa and the birth was an embarrassment. She had become pregnant and hurriedly married a man who left before the baby was born. It was for the best; the man had been unkind. But now here was Lucy, unmarried with a child in a small farm town. The shame.1

The year before, 1923, the Austrian scientist Karl Landsteiner and his family arrived in New York City. Landsteiner had been born in Vienna and it was there that he had spent most of his life and career. World War I had ravaged the city. Electricity was spotty. The trees around Landsteiner’s Vienna home had been cut for firewood. And, as a person of Jewish descent, Europe was becoming an unwelcome place. So Landsteiner accepted a position at the Rockefeller Institute, where he could continue his research in immunology, hematology, and serology. The most significant thing was to continue his research.

In 1929, Lucy remarried. This time to a local farmer. Hard workers and determined to do well, they began a life together on a farm east of town. Soon after they were married, Lucy became pregnant again. A new husband. A new child. A new life. She was relieved. Her cheeks stopped burning.

When Landsteiner arrived in America, he had already done what many would deem his most important work. He had classified human blood into types—A, B, AB, and O—making blood transfusions possible. He had isolated the polio virus and demonstrated how the immune system works. Landsteiner was known to be quiet and meticulous in his research, conducting experiments repeatedly to ensure findings were consistent. Few things outside of science held his attention. Luckily, there was more to do. Always more to do.

Lucy’s happiness was brief. The child was born sickly and lived only ten days.

Landsteiner had a son. Just one. He had married late and was practically an old man in 1917 when he became a father at age forty-nine. And now his son was being raised in America and becoming an American. When he first arrived in the U.S. and was asked by the director of the Institute what accommodations he would need for his family, Landsteiner said, “A little cottage by the sea with a rose garden.”2 They found him a flat in the city with neighbors who played the radio late into the evening. It was oppressive. His small pleasures had been left behind in Europe.

Lucy conceived again. She gave birth in the big iron bed with a doctor in attendance, her husband outside trying to finish the chores. The child was stillborn. In a record of family births there are three entries in a row that say, “baby boy, stillborn.” The dates of birth are marked as unknown. They buried the stillborn babies on their land, first having to obtain permission from the town. What was wrong? No one could tell them. Was this Lucy’s punishment?

In 1930, Landsteiner won the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his work classifying blood groups. In his Nobel lecture he said, “All in all, the results of blood transfusions are already highly satisfactory, and we have reason to hope that a thorough study of cases with undesirable after effects will help us to assess the significance of the suspected causes and perhaps reveal unknown causes.”3 Which is what he did.

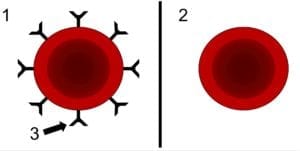

He continued to refine his blood group research. In the late 1930s, with colleague Alexander S. Wiener, he injected rabbits with the blood of rhesus monkeys and noted an immune response caused by a previously unidentified antigen on the red blood cells. A similar antigen found in human blood they called the Rh factor, for rhesus.

The Rh factor is now considered the second most important component in classifying blood, after the primary blood groups. Whether or not a person has the Rh antigen is what makes a blood type positive or negative; blood type A+ means a person’s blood is of the A group and also has the Rh antigen. About 85 percent of the population is Rh positive. Lucy was Rh negative.

Darlene remembers when her sister was born. It was 1933 and doctors had a new procedure that could induce labor. Still unsure of the cause of Lucy’s previous stillbirths, they believed the best option was to birth the baby before it died in the womb. Lucy and her husband traveled to a hospital in the nearest city when she was seven months pregnant. Darlene, at home with her grandparents, could feel the tension and worry as they waited for the news. They received a phone call and her grandmother shouted, “We have a live baby!” And the baby kept on living: month one, year one. Everyone believed the baby had lived because labor had been induced early, but that was not the reason. How were they to know the child that lived was Rh negative, like Lucy? How were they to know just how vital that was? Landsteiner had not yet completed his work.

The significance of Landsteiner and Wiener’s discovery went unrealized until 1940, when Philip Levine and Rufus Stetson connected the new Rh antigen to hemolytic disease in newborns. Hemolytic means the breaking down of red blood cells. Symptoms at birth can include pale or yellow skin, an enlarged liver or spleen, swelling, and trouble breathing. It can result in death.

This is what was happening in Lucy’s womb: An Rh negative mother’s immune system sees her baby’s Rh positive red blood cells as foreign. Her immune system makes antibodies to fight the foreign cells, causing the baby’s blood to break down. The immune system stores the antibodies to fight off the cells should they return, which they do, in subsequent pregnancies.

Lucy’s next child was also a girl. Rh positive. She lived three months. One afternoon, while Lucy was feeding the tiny thing, she said to Darlene, “Come and kiss your baby sister goodbye. She is dying.” Her spleen had ruptured. Worried the baby would be cold and afraid when they buried her, the two living sisters insisted they dress her in a pink sweater and hat set. They wrapped her in a blanket. “Now she’ll be warm,” they said.

Lucy worried it was her original indiscretion that had brought this on them. And while it was not the way Darlene was conceived, it was her birth. During the delivery, Darlene’s Rh positive blood mixed with her mother’s. In that moment, Lucy’s blood unleashed the antibodies that would later cross the placenta to fight the Rh positive cells of her other children.

Today a woman has a blood test early in her pregnancy and if she is Rh negative receives an injection of Rho(D) immune globulin, a medication that will prevent her from making Rh antibodies. That is today. From 1930 through 1949, infant mortality rates declined by 52 percent.4

Lucy carried ten children. Six died.

Personal accounts note that Landsteiner was a serious man, sometimes grim. The weight of the World Wars pressed on him, even while his own discoveries saved the lives of many soldiers. Perhaps he felt the burden of the lives he could not save, had not saved, his work always trying to keep up.

The year after Landsteiner’s death, in 1944, Lucy gave birth to a daughter who was Rh positive. In light of Landsteiner and his colleagues’ discoveries, the baby received a blood transfusion.

She lived.

End notes

- Lucy Reyburn Rittgers is the author’s great grandmother. All information included here about Lucy is from family members, unpublished family documents, and the author’s own relationship with her great grandmother.

- Heidelberger, Michael. “Karl Landsteiner 1868-1943: A Biographical Memoir.” National Academy of Sciences, 1969.

- Landsteiner, Karl. “On individual differences in human blood,” Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1930.

- “Achievements in Public Health, 1900-1999: Healthier Mothers and Babies.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. October 01, 1999/48(38); 849-858.

References

- “Achievements in Public Health, 1900-1999: Healthier Mothers and Babies.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. October 01, 1999/48(38); 849-858.

www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm4838a2.htm - Harbison, Corey. “Karl Landsteiner (1868-1943).” The Embryo Project Encyclopedia. (2017).

embryo.asu.edu/pages/karl-landsteiner-1868-1943 - Heidelberger, Michael. “Karl Landsteiner 1868-1943: A Biographical Memoir.” National Academy of Sciences, 1969.

www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/landsteiner-karl.pdf - “Hemolytic Disease of the Newborn (HDN).” Stanford Children’s Hospital, accessed November 12, 2019.

www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/default?id=hemolytic-disease-of-the-newborn-90-P02368 - Karl Landsteiner Biographical, from Nobel Lectures, Physiology or Medicine 1922-1941, Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1965.

www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1930/landsteiner/biographical/ - Landsteiner, Karl. “On individual differences in human blood,” Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1930.

www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/landsteiner-lecture.pdf - Pearson, H. “History of Pediatric Hematology Oncology.” Pediatr Res 52, 979–992. (2002). doi: 10.1203/00006450-200212000-00026.

www.nature.com/articles/pr2002282?proof=true

“The Rh Factor: Enhancing the Safety of Blood Transfusion and Setting the Stage for Preventing Hemolytic Disease of the Newborn,” The Rockefeller University, accessed November 15, 2019. centennial.rucares.org/index.php?page=Rh_Factor - Schwarz, Hans Peter and Friedrich Dorner. “Karl Landsteiner and His Major Contributions to Haematology.” British Journal of Haematology. (May 2003).

doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04295.x - Woodward, Billy, Joel Shurkin and Debra Gordon. Scientists Greater Than Einstein: The Biggest Lifesavers of the Twentieth Century. Quill Driver Books. (2009).

PAULA CARTER is the author of the flash memoir collection No Relation. Her essays have appeared in The New York Times, Kenyon Review, The Southern Review, Prairie Schooner, Creative Nonfiction, and elsewhere. Based in Chicago, she is a part of the live lit community and is a company member with the storytelling group 2nd Story. She holds an M.F.A. from Indiana University, Bloomington and currently teaches creative nonfiction at Northwestern University.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest & Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 2 – Spring 2020

Leave a Reply