| DA VINCI AT 500 |

| Published in December, 2019 |

| H E K T O R A M A |

| . |

| The year 2019 celebrates the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci, one of the greatest painters and polymaths of all time. Born near Florence in 1452, he moved to Milan at age thirty, but towards the end of his life (1516) was recruited by King Francis I to move to France. He died in the Castle of Amboise three years later on 2 May 1519. An unverified story tells that he died in the arms of his patron and protector, King Francis. We honor the achievements of this great man by reprinting several articles published about him in our journal. |

|

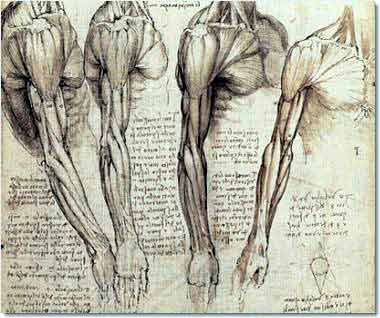

Leonardo da Vinci was a “Renaissance man” in the truest sense, contributing his inexhaustible talent to many fields, including anatomy. In a time when medicine was still rudimentary and dissection was viewed with disdain, Leonardo plowed through with his keen intellectual curiosity and honed draughtsman skills. His work on anatomy can grossly be divided into two stages: his earlier artistic pieces and his later analytical studies.1 Leonardo’s earliest studies focused on illustrating ancient texts and indulging in anatomical explanations of metaphysics; he was concerned with the soul and the eye as a means to both localize the soul and better understand artistic perspective. His later scientific blossoming drove his interest in observational description of the human body, its function, and its relation to the world. Leonardo’s growth from metaphysics toward a more empirical science informed not only his drawing style, but also the content and presentation of his anatomical works.

|

| DA VINCI AS ANATOMIST | ||||

|

|

|

|||

|

||||

| LEONARDO AND THE REINVENTION OF ANATOMY | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| THE CURIOUS TALE OF LEONARDO DA VINCI & THE SPHERICAL UTERUS | ||||||||

|

||||||||

Leave a Reply