Carol-Ann Farkas

Boston, Massachussetts, United States

In the late nineteenth century, many women who dared to study and practice medicine tempered that radical move with the reassuring insistence that, by virtue of their sex, they could combine medical knowledge with feminine, maternal guidance for the physical and moral well-being of their patients. The gender essentialism of such arguments—so problematic to us now—authorized the medical woman to venture into a range of contemporary social controversies. In her 1892 novel Helen Brent MD: A Social Study,1 Annie Nathan Meyer’s unsubtle, melodramatic plot affords the eponymous heroine multiple opportunities to comment on everything from egalitarian, dual-career marriages, to the scourge of syphilis spread by “the husband fiend,”2 to the role of nervous exhaustion in women’s physical, intellectual, and moral health. Throughout, the novel reinforces an idealistic, traditional vision of so-called womanly “purity,” even as Helen makes the case that traditional sex roles are not merely constraining, but fundamentally unwholesome.

|

|

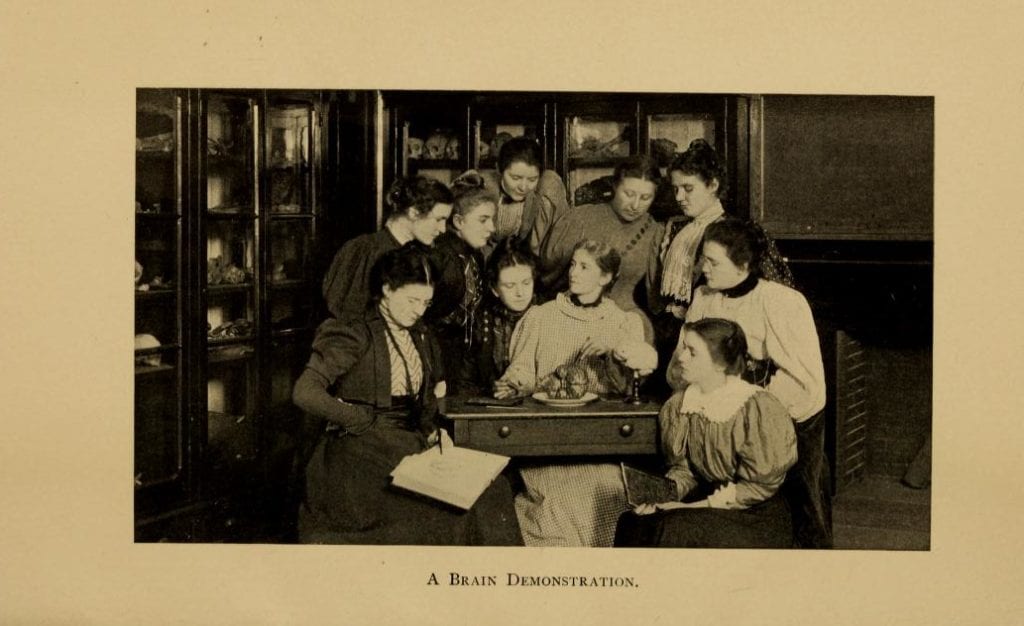

“A Brain Demonstration.” In: Daughters of Aesculapius: Stories Written by Alumnae and Students of the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs and Co.; 1897. https://archive.org/details/daughtersofaescu00woma/page/n7. |

The novel is impressively, if demoralizingly, prescient. Dr. Helen Brent, brilliantly successful in her career at a New York teaching hospital, struggles with “work-life balance,” especially the frustration of being unable to find a worthy romantic partner who is not intimidated by her success: men might greatly admire accomplished women like Helen and enjoy their intellectual companionship, but prefer to go home to pretty, traditional girls whose only ambitions are to please their husbands. Helen’s love interest, Harold Skidmore, cannot imagine himself as a pioneer supporter for the professional woman: “I cannot attempt to change the world. It is generally conceded that a man’s career is more important than his wife’s. It is so in the nature of things.” Helen is forced to reply: “Then I shall never marry until I can find the man that together with me will be courageous enough to try to change the world” (33).

Helen laments a sexual double standard allowing men to achieve their potential, while women are denied choice, degraded, and trapped: “Many a broken-down woman comes to me,” she says, “wearing her life away, draining her entire nerve force on mere household drudgery . . .” (109). Helen is especially critical of the women of her own class who perpetuate oppression by raising ignorant, passive daughters concerned with nothing more serious than making a good marital match. Helen bluntly repeats a tenet of established feminist thought, that “women have lived so long in such a narrow sphere that their judgement is warped. They have become conservative through seeing only one phase of life” (102).3–6

Contrary to then-prevalent beliefs7 that work and study might drain a woman’s so-called vital energies, Helen’s experience has taught her that young women thrive when both body and mind are exercised:

“I have had brought to me any number of cases of nervous prostration. Very few of these have been brought about by over-study. . . . I have . . . seen hundreds of cases where the breakdown has been caused by over-dissipation. I have seen pneumonias resulting from the absurdly inadequate clothing of the fashionable evening world; I have seen severe anemia resulting from irregular hours and consequent loss of sleep; I have seen many other troubles brought on by the constant strain that social duties lay upon the entire nervous system.” (5-59)

Helen’s prescription for her female patients is very much in keeping with progressive notions of health reform:8 “Loose, sensible, plain gowns. Gymnasium at least twice weekly. Horseback or bicycle tri-weekly for an hour in the morning, after light breakfast. Early hours for retiring. Liberty to seek the quiet of her own room, if desired. Liberty to seek the companionship of her classmates” (63).

Meyer, through Helen, insists that no one can achieve physical, intellectual, or moral health without independence, rewarding work, and egalitarian relationships. Helen’s friends, the Dunnings, offer the ideal mindset for modern, dual-career marriage. Mr. Dunning cannot imagine his wife trapped in traditional roles: “from a satisfied, active, sympathetic companion as she always has been . . . she would soon degenerate into one of those nervous, discontented, narrow-minded and unsympathetic wives that men often force their better halves into becoming” (116-17).

As Meyer makes the connection between women’s intellectual development and moral health, she engages directly with contemporary cultural meanings of “nervous illness.”9,10 Diagnoses such as neurasthenia, hysteria, and nervous exhaustion, emerging from the new fields of neurology and psychology, operated in the zeitgeist alongside anxieties about a rapidly changing, “modern” culture. As Schaffner explains, health beliefs of the time mingled post-Darwinian, racist fears about evolution with unease about an increasingly diverse, less stratified society. Nervous weakness was one of several “deficiencies” threatening white, middle-class culture, along with “perverse” sexual practices, alcoholism, and criminality (332). As represented by the theories of Kraft-Ebbing and Nordau, nervous disorders could be read as a sign of susceptibility to backwards “devolution” or degeneration.10–12

Accordingly, our medical woman insists that nervous exhaustion is directly correlated with various forms of degradation. For women especially: kept in deliberate idleness and ignorance, their capacity for sound moral judgment has been stunted, and in an important sense diseased, leaving them susceptible to contaminating external influences. In particular, Meyer is unsparing in her criticism of a social system that tacitly encourages the unwholesome monstrousness of sexually-rapacious men, preying on rich and poor women alike:

“. . . [T]he cruelty of the social structure of morals was brought before her with particular violence. Here in the hospital now lay a woman whose future was utterly wrecked, whose physical condition was utterly ruined, who, if possibly spared to life, would have no future, no outlook, who would be shunned and pitied . . . and the father of her child, where was he? No doubt sitting at this moment in one of the most elegant houses on Fifth Avenue, his arms about a young girl, who was about to unite her fresh, innocent life with his, who yet would have shrunk in horror and disgust from this poor, ruined woman.” (71)

This man, the greatest catch in New York’s social circles, infects several women with a nightmare version of syphilis. Despite his wealth and social power, Verplanck is the embodiment of late-century concerns about degeneracy and impurity. Evolutionarily-speaking, he is weak and defective—in Meyer’s view, his propensities to physical and moral illness are united to make him a menace to helpless women and children, providing a clear, urgent rationale for the “purity” campaigns that dovetailed with the women’s movement of the late nineteenth century.2,13 Verplanck’s victims include the socialite sister of Helen’s protegée, as well as the wife whom Harold chooses precisely because she is more delicate than Helen—and, it turn out, more vulnerable as a result. Pretty, but poorly educated, bored, and nervous, Harold’s wife is tempted into an affair with Verplanck, which kills her and her baby. Sexual weakness and nervous weakness are represented as co-morbid, associated as cause and consequence of moral disease.

Verplanck is the vector of contagion in the absence of sufficient moral hygiene: his wealth and status make him irresistible to society matrons so avaricious that they will trade their children’s health for a profitable marriage. Here, Meyer indicts the upper classes as pathologically corrupt, thus creating several mechanisms for the spread of degeneracy. But neither Helen nor Meyer can stop Verplanck’s threats to purity, because a hypocritical prudishness guarantees that no one can talk freely about the problem in polite company, or polite fiction. Meyer is limited to euphemistic gestures, with her protagonist becoming increasingly frustrated that “decorous” silence is allowing a terrible threat to go unmet.13 Notably, when Helen has to tell one mother about the danger her daughter faces by marrying Verplanck, Meyer can only provide the most oblique narrative:

Mrs. Bayley: “[Y]ou don’t really think that such a handsome young man with such an enormous fortune could have lived the life of a saint. If I listened to you, I might as well make up my mind to have my daughters remain old maids to the end of their days.”

Helen’s reply: “I shall tell you what you force me to say, which I’m sorry is what is necessary to say . . .” (76-79)

The advantage of this fictional narrative is that it allows Meyer, through Helen, to appeal to readers’ intellects, amplified with an appeal to their emotions. The disadvantage, of course, is that unlike the more controversial New Woman novelists of the same period,14 Meyer cannot risk “saying what is necessary to say” about issues such as sexually-transmitted diseases and their threat to the health of her community, not if she wants to reach as mainstream an audience as possible. What Meyer can do is engage our sympathies with her protagonist, as both role model and antidote: the medical woman, as an exemplar of physical, intellectual, and moral strength, points the way forward for readers.

Representing the related causes of women’s professionalization and the purity movement, Helen Brent MD asserts that the demands of conventional gender roles leave women with attenuated nervous and moral fiber, and liable to have their health ruined by sexual promiscuity and venereal disease. Meyer draws directly from the contemporaneous discourse of women’s rights, purity campaigns, and beliefs about the interplay of body, mind, and nerves, arguing that “old fashioned” gender roles render women susceptible to physical and moral corruption, and in turn leverages that argument to underscore the need for progressive education and work for women. At a moment when social norms and gender roles were unstable, evolving phenomena, authors like Meyer could conflate them into one biopsychosocial problem for which women’s increased professional and moral authority provided a holistic therapy.

References

- Meyer AN. Helen Brent MD: A Social Study. New York: Cassell; 1892.

- Liggins E. Writing Against “the Husband Fiend”: Syphilis and Male Sexual Vice in the New Woman Novel. Women’s Writ. 2000;7(2):175-195.

- Wollstonecraft M. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. London: Walter Scott; 1792.

- Cobbe FP. The Final Cause of Woman. In: Butler JE, ed. Woman’s Work and Woman’s Suffrage. London: Macmillan and Co; 1869:1-26.

- Fawcett MG. The Emancipation of Women. Fortn Rev. 1891;56:673-685.

- Stanton, Elizabeth Cady; Anthony, Susan B; Gage, Matidla Joslyn; Harper IH. History of Woman Suffrage. New York: Fowler and Wells; 1902.

- Clarke EH. Sex in Education, or a Fair Chance for the Girls. Boston: James R. Osgood and Co.; 1874.

- Hardes JJ. Women, madness’ and exercise. Med Humanit. 2018;44(3):181-192. doi:10.1136/medhum-2017-011379

- Barke, Megan, Rebecca Fribush PNS. Nervous Breakdown in 20th Century American Culture. J Soc Hist. 2000;33(3):565-584.

- Schaffner AK. Exhaustion and the Pathologization of Modernity. J Med Humanit. 2016;37(3):327-341. doi:10.1007/s10912-014-9299-z

- von Krafft-Ebing R. Ueber Gesunde Unde Kranke Nerven (On Healthy and Diseased Nerves). 4th ed. Tubingen: Verlag der H. Laupp’schen Buchandlung; 1898.

- Nordau M. Entartung (Degeneration). 3rd ed. Berlin: Duncker; 1896.

- Skinner C. “The Purity of Truth”: Nineteenth-Century American Women Physicians Write About Delicate Topics. Rhetor Rev. 2007;26(2):103-119.

- Heilmann A. The New Woman in the New Millenium: Recent Trends in Criticism of New Woman Fiction. Lit Compass. 2005;3(1):32-42.

CAROL-ANN FARKAS, PhD, is Professor of English in the School of Arts and Sciences at MCPHS University in Boston. She teaches writing, nineteenth-century fiction, and narrative and medicine. A scholar with a background in Victorian and cultural studies, she currently specializes in the interdisciplinary study of medicine and wellness in popular culture. She is a founding member of the MCPHS Center for Health Humanities, and in 2020 will direct a new undergraduate degree program in health humanities. Her most recent publication is an edited anthology published in 2017, Reading the Psychosomatic in Medical and Popular Culture: Something, Nothing, Everything (Routledge).

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 1 – Winter 2020

Fall 2019 | Sections | Books & Reviews

Leave a Reply