| LATIN AMERICA |

| Published in September, 2019 |

| H E K T O R A M A |

| . |

| AFRICAN AMERICAN MEDICAL PIONEERS | ||||||

|

||||||

| DANIEL CARRION AND HIS DISEASE | ||||

|

|

|

|||

|

||||

| THE VAN BUREN HOSPITAL IN THE HISTORY OF CHILE | |||||

In the sixteenth century Valparaiso was a small village with a few hundred inhabitants. Despite this, it was the principal port of the Kingdom of Chile, where ships from Europe arrived after the long and dangerous passage around Cape Horn. In this port ships took on food and water. The village had no hospital, but despite this it received those who had become ill on the voyage. In 1786 King Charles III of Spain issued a royal proclamation ordering “the erection of a hospital in the Port of Valparaiso under the care of the Religious Order of San Juan de Dios.”1 In the founding charter it was established that the soldiers of the garrison and the crews of the merchant ships should pay for their hospital care, and that only if resources were sufficient could women also be treated. It was only after 1836 that the hospital began to accept women as patients.

|

|||||

| A LESSON IN HORIZONTALITY: A HOSPITAL SAN VICENTE DE PAUL IN MEDELLIN, COLUMBIA | |||||

The Hospital San Vicente de Paúl in Medellin, Colombia was built in 1913 to serve the need of the growing township and its working class. It was built in the outskirts of the city, to facilitate the intrinsic connection between the farmers in the hills, which still come to trade during the day to Medellin and the laborers from the surrounding factories and industries. Many of its patients came because of work-related injuries: suturing finger by finger, machete slash after machete slash, and in the most definitive and mournful of situations, an amputation. Perhaps the initial need it served eventually made the institution one of the most celebrated transplant centers in Colombia and Latin America: “Sic Parvis Magna,” as Francis Drake, who knew his fare share of lacerations during his life at sea, would have said. Within the accolades of El Hospital is the first simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplantation, as well as the first heart, and lung transplant in Colombia.1

|

|||||

| GORGAS HOSPITAL, ANCON, PANAMA | |||||

A man, a plan, a canal: Panama. This well-known palindrome describes the grand vision of Count Ferdinand de Lesseps for constructing, under the flag of France, a sea level canal linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans in the late nineteenth century. Despite the best efforts of the French, the plan for a canal was abandoned, only to be revived by a team of American engineers who, with the support of a large workforce, created a successful path between the seas by 1914. Working somewhat behind the scenes but of equal importance were Dr. William Crawford Gorgas and his dedicated public health team who helped assure that tropical diseases would not prevent the completion of the grand project. Part of that effort was mobilized through the doctors, nurses and other health professionals who served at the main hospital on the isthmus later named in honor of Gorgas. The hospital was not originated by Dr. Gorgas, however. Shortly after the arrival of Count de Lesseps in 1881, a small temporary medical facility called Strangers Hospital was built on the upper slope of Ancon Hill, near Panama City. It was replaced in 1882 by a much larger facility to serve the sick and injured employees of the French Canal Company. Constructed on the lower slope of the hill, the 700 bed L’Hopital Central du Panama was dedicated during a Pontifical Mass on September 17 of that year.

|

|||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

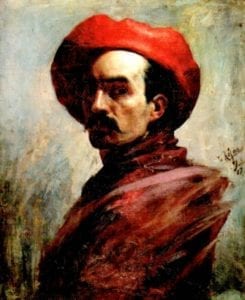

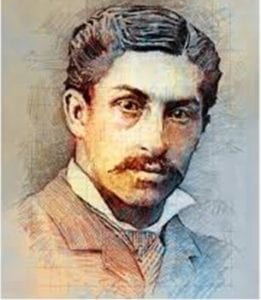

Tuberculosis, the “captain of all these men of death,” has devastated diverse societies for thousands of years. How are experiences related to this unforgiving and seemingly insatiable disease made unique by their cultural contexts? The visual arts provide a record of this disease as it relates to specific cultures. Venezuelan artist Cristóbal Rojas Poleo (1858-1890) captured the depth of familial pain caused by consumption, which cut short his own life. While surrounded by the shadow of death Rojas painted a cultural response to tuberculosis, portraying familial intimacy, nurturing care, and shared faith—all themes specific to Latin America. More than a century later, Rojas’ response to his illness seem to transcend his era and exemplify timeless aspects of Latino culture.

|

Hektorama

Leave a Reply