Soleil Shah

London, UK

|

| A shell-shocked soldier receives electro-shock treatment from a nurse during the First World War. Image Source: Otis Historical Archives National Museum of Health and Medicine (ref Reeve 041476) via Flickr |

“Wherever the art of medicine is loved, there is also a love of humanity.” – Hippocrates

War neurosis, or “shell shock” as it was referred to in the twentieth century, could be considered the signature injury of World War I. These disorders involved nervous ailments with no apparent organic lesion. Symptoms included paralyzed limbs, mutism, and the localized loss of sensation or numbness, as well as uncontrolled emotions and “male hysteria.”1 During the First World War, 80,000 British cases of war neurosis were diagnosed and, after the war, around 200,000 British veterans were awarded pensions for war-related nervous diseases.2 The English psychiatrist and anthropologist William Halse Rivers (W.H.R.) Rivers (1864-1922) famously treated British officers suffering from shell shock by revolutionary methods known for their humaneness. These included “talk therapy” and autognosis, which were influenced by his own physiological and ethnographic research, as well as his studies of psychoanalysis and evolutionary theory.

Before World War I, physicians and researchers believed that shell shock was due to physical injury of the nerves and exposure to heavy bombardment and advocated a “physical” approach to treatment with drugs, surgery, electricity, hydrotherapy, massage, or other kinds of physiotherapy.3 These methods were both physically and emotionally harrowing. Fritz Kaufmann, staff physician at the Nervous Illness Station of the Reserve Infirmary at Ludwigshafen, Germany, described his approach to treating servicemen suffering from war neuroses in his writing. Kauffman recommended a “surprise attack,” or prolonged electrical currents combined with verbal suggestions and persuasion. He believed that by treating the physical “motor symptoms” associated with nerve damage, physicians could also cure the psychological symptoms.4

Rivers, an extraordinarily gifted child raised in Kent, graduated from medical school at the University of London at twenty-two. When he began working at the National Hospital for the Paralyzed and Epileptic at Queen Square in 1886, he encountered physical treatments similar to those advocated by Kauffman. As these treatments were often ineffective, Rivers became interested in developing them and even predicted that symptoms of hysteria would in time be associated with “molecular” changes in the nervous system.5 Around the same time, Rivers also published reports on certain psychological conditions: Delirium and its allied conditions (1889), Hysteria (1891), and Neurasthenia (1893) – perhaps indicating a budding interest in psychological therapies.

Shortly after, Rivers’ explorations and emerging interests in physiology and psychology led him to attend a Cambridge-led expedition to the Torres Strait. Here, Rivers engaged in ethnographic research, comparing the color vision of the aboriginal Melanesian islanders with the visual acuity of “civilized” people. Rivers’ Melanesian research marked the beginning of his second career as an anthropologist and also developed his new interests in evolutionary theories behind psychology.

In 1908 Rivers published The Todas, an ethnographic study on the Todas inhabitants of southwest India. In his writing, Rivers demonstrated a deep consideration of the evolution of the mind. He referred to the growth of the human intellect as a “continuous addition to a sequence.” In other words, basic instincts were not removed through evolution, but instead pushed aside as newer, more complex instincts form.6 These theories were similar to the famed neurologist John Hughlings Jackson’s theories of evolution and consciousness, published only a few decades earlier. Jackson believed that the nervous system consisted of “levels” that had been laid down at different evolutionary moments and that these levels corresponded to functions rather than anatomical structures.7

Rivers, however, did not fully accept all of Jackson’s ideas. Jackson, in the 1880s, subscribed to the Lamarckian idea that a “freeze” response from soldiers at battle could be explained as a memory of ancestral survival mechanisms. However, by 1915 and around the peak of Rivers’ career, Lamarckian inheritance and the idea of “phylogenetic memory” was generally rejected.8 Instead, inheritance was translated into Mendelian and Darwinian terms. Thus, Rivers proposed that regressions do not result from phylogenetic memories of ancestors, but instead stem from traumatic life experiences and the complex organization of the nervous system. These life experiences would cause individuals to “climb down a neurological ladder” and use older, evolutionarily speaking, levels of the brain to mimic the attitudes and dispositions characteristic of their ancestors.9

In 1915 Rivers moved from Queen Square Hospital to work at Maghull War Hospital. Maghull, at the time, was in the midst of a transition. Its director, neurophysiologist R.G. Rows, had undergone an intellectual conversion after reading Freud and became determined to develop Maghull in a psychological direction rather than along “physicalist” lines.10 At Maghull, Rivers conversed with psychologist T.H. Pear about psychological medicine, Hughlings Jackson and Freud’s ideas, and anthropological theories. In a memoir, Pear recalls Rivers’ intense interest in Freud on arriving to Maghull, writing “[Rivers’] first desire was to grasp what Freud meant by the Unconscious, which Rivers thought was the most important contribution to psychology in a long time.”11 Freud’s approaches to psychotherapy and searching for unconscious “conflicts of the mind” seemed revelatory to Rivers. Most doctors treating shell shock who rejected an appeal to physical etiologies were not sympathetic to complex psychological explanations, or even basic psychotherapies. Symptoms could be recognized as “emotional,” but the best cure was considered “hard manual work or breathing exercises.”12 Most doctors also suggested that patients with shell shock actively try to repress and forget their war experiences.

Yet Rivers also distinguished his ideas from Freud’s premises.13 Rivers saw the instinct of self-preservation as the driving force behind shell shock and other similar psychological ailments, while Freud attributed this force to sexual instinct. In other words, Rivers believed that memories were repressed because there was a “conflict between the mental tendencies of the individual and the traditional code of conduct prescribed by society” instead of sexual strivings.

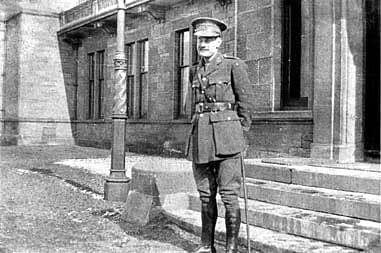

|

| W.H.R. Rivers standing outside of Craiglockhart Hospital in 1916. Image Source: The Heritage of the Great War website |

Rivers used cases of shell shock from World War I to support his ideas because war neuroses afflict “persons whose sexual life seems to be wholly normal and commonplace, who seem to be singularly free from sexual repressions which are so frequent…among the most leisured classes of the community.”14 This conclusion led Rivers to develop his treatments of “talk therapy” and autognosis. Instead of using Freudian methods of repression, drugs, suggestion, and hypnotism, Rivers recommended that soldiers instead talk about war anxieties and experiences to cope with their fears. Rivers also encountered patients whom he attempted to “re-educate” by directing attention to a neglected aspect of a negative experience. One patient specifically remembers encountering his dead friend in the trenches with his limbs torn off of his body after an explosion. Rivers suggested that the patient imagine that his friend has been killed outright, rather than having to undergo prolonged suffering. This positive re-imagination of the memory helped the patient improve his outlook and significantly reduced his neuroses symptoms.

Rivers eventually left Maghull War Hospital to work at Craiglockhart War Hospital, a former spa near Edinburgh. At Craiglockhart he administered his own unique treatment techniques, which rarely involved physical methods, to different forms of war neuroses. For traumatic hysteria, Rivers mainly used suggestion, persuasion, re-education, and hypnosis.15 For anxiety neurosis, more typical in officers returning with shell shock, Rivers used autognosis – a two-part process. The first involved educating the patient in psychology and physiology, helping him to realize that the illness he was experiencing was neither “strange” nor permanent. The second part was talk therapy, which helped patients contrive ways to deal with patterns of neurological disturbances. This involved discussing traumatic experiences at an in-depth level with patients or helping them view their experiences in more positive ways.16

A forward-thinking polymath, W.H.R. Rivers combined and modified elements of Jackson and Freud’s work with his own ideas, influenced by years of field research and travel, to develop novel methods for treating shell shock. These methods humanized patients through sympathetic interactions rather than pathologizing them through an outdated and cruel physicalist approach. Indeed, Rivers’ pioneering work was considered to be one of the first times humane treatments were applied in psychiatry, demonstrating to future generations of doctors and medical students that science and humanism are not incompatible.

End Notes

- Young, Allan. “W.H.R. Rivers and the war neuroses.” Journal of the History of the Behavioural Sciences. 35:4. Pp.359-378. 1999

- Barham, Peter. Forgotten Lunatics of the Great War. Yale University Press. 2004. [Part 1: The War Mental Hospital. pp.31-94]

- Ibid.

- Kaufmann, Fritz. “The Systematic Cure of Complicated Psychogenic Motor Disorders Among Soldiers in One Session” (1916). [From Madness to Mental Health. ed. Eghigian, Greg. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2010).] pp. 233-238

- Young, Allan. “W.H.R. Rivers and the war neuroses.” Journal of the History of the Behavioural Sciences. 35:4. Pp.359-378. 1999

- Rivers, W.H.R. The Todas. Cambridge University Press. 1908.

- Young, Allan. “W.H.R. Rivers and the war neuroses.” Journal of the History of the Behavioural Sciences. 35:4. Pp.359-378. 1999

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Pear, T.H. “Reminiscences” (1959). Mimeo. Archives of the British Psychological Society. University of Liverpool.

- Ibid.

- Loughran, Tracey. “Shell-Shock and Psychological Medicine in First World War Britain.” Social History of Medicine. 22. 2009. pp. 79-95

- Stone, Martin. “Shellshock and the Psychologists.” Anatomy of Madness Volume III. Edited Bynum, William F., Porter, Ray Shepherd, Michael. New York: Routledge. 2004. pp.242-71

- Rivers, W.H.R. Instinct and the Unconscious. London: 1919. [Appendix III “The Repression of War Experience” (pp.185-204)]

- Rivers, W.H.R.. “War Neurosis and Military Training” (1918). [From Madness to Mental Health. ed. Eghigian, Greg. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2010).] pp. 238-244

- Ibid.

SOLEIL SHAH lives in London and is a US-UK Fulbright Scholar pursuing an MSc in international health policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He grew up in the charming town of Bow, New Hampshire, and will attend medical school at Stanford this fall.

Spring 2019 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply