Kevin R. Loughlin

Boston, Massachusetts, United States

|

| Fig 1. The Leonard Zakim Bridge, Boston |

“If Warren had lived, Washington would have remained an obscurity.”

– Peter Oliver, former chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court

On June 17, a late spring New England morning, thousands of Bostonians will begin their day by traveling over the Zakim Bridge. Few will be aware of the significance of the bridge’s obelisk supports, and fewer still will note the obelisk reaching skyward against the eastern horizon. This obelisk commemorates the events of June 17, 1775, the Battle of Bunker Hill, or more accurately, Breed’s Hill. (Figure 1, 2)

What occurred on that day on that site has faded into the vault of history, its significance largely forgotten. Among the participants was the thirty-four-year-old physician Joseph Warren. Much like the battle he fought in, Warren has largely been relegated to an anecdote of history. What makes Warren’s disappearance from the luminaries of the American Revolution even more incredulous is that he is the only person known to have had a role in the Boston Massacre, the Boston Tea Party, the ride of Paul Revere, the battles at Lexington and Concord, and the Battle of Bunker Hill.

The young Warren was a critical leader in both the medical profession and among the patriots. A descendant of the Mayflower settlers, he was born in Roxbury, Massachusetts, and attended Harvard College. Like many young American physicians of that era, he received his medical training as an apprentice to an older physician. Doctor James Lloyd, one of Boston’s most respected physicians, had received some of his training in London and on returning to Boston had become a leader in the medical profession. He championed smallpox inoculations and advocated obstetrical care based on the teachings of Doctor William Smellie, a Scotsman whose lectures he had attended in London.1 Warren absorbed this knowledge and became a vocal advocate of smallpox vaccination, which he administered in the nearby Castle William.2 Smallpox was known as the “speckled monster” and at the time vaccination was controversial among both physicians and the citizenry. Warren advanced the standard of medical care by both his vaccination advocacy and by his involvement in obstetrical care, which had typically been left to midwives.

|

| Fig 2. The obelisk at the Bunker Hill Memorial |

As his medical practice grew, so did Warren’s engagement in the politics of the day. From 1769 onward, he was a vital member of the Committee of Correspondence, which shaped most of the political initiatives of the colonists. In April 1770, Warren was one of the physicians who provided care for the wounded at the Boston Massacre. He was chosen to perform the autopsy on Christopher Seider, the youngster whose death initiated the events of the Massacre.3,4 Over the ensuing years, the tensions between Parliament and the colonists grew. On May 10, 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act, which granted the British East India Company a monopoly on the exportation of dutied tea to the colonies. This restriction of free trade was viewed by the colonists as an expansion of British control over goods coming into the colonies.

The first cargo of dutied tea arrived in Boston on board the Dartmouth on November 28. By British law, the vessel had twenty days, until midnight on December 16, to unload its cargo and pay the duties. Soon thereafter, two additional ships, the Eleanor and Beaver, arrived in the harbor loaded with tea. Colonial leaders, Samuel Adams among them, tried to negotiate with Governor Hutchinson to turn back the three ships to England without imposition of taxes. Hutchinson refused. On the evening of December 16, several dozen Bostonians dressed as Mohawk warriors boarded the three ships and dumped their cargoes into the harbor. Warren was not one of the “Indians” but was intimately involved in the planning of the activity.5,6 The Tea Party was not without consequences. Parliament responded by passage of the Intolerable Acts, which restricted the freedom of the colonists and further heightened tensions with the British. This resulted in the publication of the Suffolk Resolves in 1774, authored primarily by Warren.7 The “Resolves” called for a boycott of British goods and a strengthening of local militias. Another illustration of Warren’s growing stature among the patriots was his selection, not once but twice, to deliver the Boston Massacre commemorative oration in 1772 and 1775. Warren’s growing ardor toward conflict is exemplified by the close of his 1775 oration, “But if these pacific measures are ineffectual, and it appears that the only way to safety is thro’ the fields of blood, I know that you will not turn your faces from your foes, but will undauntedly press forward ‘till tyranny is trodden under foot….”8

|

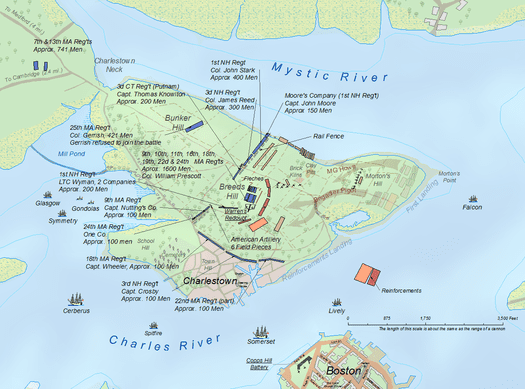

| Fig 3. Map of the Battle of Bunker Hill |

It is speculated that Warren organized a spy network, made possible primarily through his patients, that provided critical information about the maneuvers of the British. It is likely that information gathered by this arrangement enabled him to learn of the British plans to capture Samuel Adams and John Hancock at Lexington and munitions at Concord. It is Warren who instructed Paul Revere to prepare for his “midnight ride” on the northern route and William Dawes on the southern route to warn the colonists of the impending British attack.9 However, Warren did much more than direct Revere and Dawes. He was an active participant in the battles which began at Lexington and Concord and continued toward Boston. In Menotomy, the current town of Arlington, the fighting became particularly intense and it was reported that a musket-ball came so close to Warren that it took off a lock of his hair.

As hostilities escalated, the confrontation that culminated at Bunker Hill seemed all but certain. On the night of June 16, one thousand men gathered in Cambridge in preparation for the inevitable confrontation with the British on the Charlestown Peninsula the following day. Warren had been appointed a major general by the Massachusetts Provincial Congress three days earlier and confided to his friend, Elbridge Gerry, that he planned on going into battle himself. Gerry was alarmed and warned him of the danger involved.11 Warren fatalistically responded with a quote from the Roman poet, Horace, “Dulce et decorum pro patria mori,” or “It is sweet and proper to die for one’s country.”12

On June 17, the fighting on the Charlestown Peninsula commenced. British warships began firing at sunrise from Boston Harbor, and the British infantry was supported by cannonballs fired from Copp’s Hill across the Charles River. Warren crossed the narrow neck leading from Charlestown to Bunker Hill. He met General Putnam, who offered Warren command of the battle, a sign of the regard in which he was held. Warren demurred and continued down to the redoubt at the base of Breed’s Hill. (Figure 3) The British had superior ground forces as well as support from the warships in the harbor and the artillery across the Charles. The fighting was ferocious and the Americans were forced to begin to retreat. Colonel John Stark, a veteran of the French and Indian War, would later comment, “The dead lay as thick as sheep in a fold.”13 Warren, although wounded, continued to fight and “lingered to the last” to cover his retreating men.14 Finally, Warren was killed by a bullet that entered beneath his left eye and exited the back of his skull. (Figure 4) As the retreat continued, his body was recognized by some of the advancing British soldiers who mutilated and decapitated his corpse.

|

| Fig 4. The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill, June 17, 1775, by John Trumbull |

On hearing of his death, Samuel Adams lamented, “The death of our truly amiable and worthy friend, Dr. Warren, is greatly afflicting. He fell in the glorious struggle for the public liberty.”15 The untimely death of Warren led some to speculate on what might have been. Thomas Hutchinson, the British governor, observed, “… if he had lived [Warren] bid as fair as any man to advance himself to the summit of the political as well as military affairs and to become the Cromwell of North America.”16 Peter Oliver, former chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court, felt that had Warren lived, “Washington would have remained in obscurity.”17 In fairness, some may argue that Oliver’s view reflects regional bias. It is fair to acknowledge, however, that Warren, unlike Jefferson, John and Samuel Adams, Franklin, and Hancock, none of whom ever saw combat, exhibited the personal courage that only those who have been in battle can understand.

One can ponder what further impact Warren would have made if he had received the gift of a full life. His medical leadership was still in its nascent stages at the age of thirty-four, but it is reasonable to speculate that he would have had a major influence on medical practice. Politically, Warren would likely have taken his rightful place among the Founding Fathers as a signer of the Declaration of Independence and an architect of the Constitution. He would have stood shoulder to shoulder with his fellow Massachusetts men, John Adams, Samuel Adams, and John Hancock.

Perhaps if the morning traffic on the Zakim Bridge is a little bit heavier on June 17, it would provide the opportunity for a few riders to pause and reflect on the events that occurred beneath the obelisk on that morning nearly two and a half centuries ago, and the debt that is owed to Doctor Warren and his fellow patriots.

References

- DiSpigna C. The Founding Martyr: The Life and Death of Joseph Warren, the American Revolution’s Last Hero. Crown, New York, 2018. pg. 55.

- Philbrick N. Bunker Hill: A City, A Siege, A Revolution. Viking Press, New York, 2013, pg. 68.

- DiSpigna C. pg.107 cited Boston Evening Post, February 26, 1770.

- Zobel HB. The Boston Massacre. W.W. Norton and Company. New York and London, 1970.

- DiSpigna C. pg.135 cited Rally Mohawks! Bring out your axes. Palmer et al. Lodge of St. Andrews, pg. 170.

- Carp BL. Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America. Yale University Press. New Haven and London, pg. 146.

- Forman SA. Dr. Joseph Warren: The Boston Tea Party, Bunker Hill and the Birth of American Liberty. Pelican Publishing Company, Gretna 2012.

- www.drjosephwarren.com/…warren’s-1775-boston-massacre-oration-manscript-transcription. Accessed 1/21/2019.

- Fischer DH. Paul Revere’s Ride. Oxford University Press. New York and Oxford, 1994.

- DiSpigna C. pg. 169 cited Brown, Rebecca Warren. Stories About General Warren in Relation to the Fifth of March Massacre and the Battle of Bunker Hill by a Lady of Boston. pg. 50-51.

- Philbrick N. pg. 215.

- Forman SA. pg.294 cited New Hampshire Gazette 3/10/1810 Austin, The Life of Elbridge Gerry.

- DiSpigna C. pg. 182. John Fellows. The Veil Removed. New York, 1843, pg. 120.

- DiSpigna C. pg. 186.

- DiSpigna C. pg.195 Fowler WM Jr. Samuel Adams: Radical Puritan. New York, 1807. pg. 141. Frothingham R. Jr. Life and Times of Joseph Warren. Boston, 1865.

- DiSpigna C. pg.196 Catherine Barton Mayo ed. Additions to Thomas Hutchinson’s History of Massachusetts, AAS Proceedings 59(1940): 11-74, esp. 45.

- DiSpigna C. pg.196 Oliver P. Origin and Progress of the American Rebellion: A Tory View. Edited by Douglass Adair and John A. Schutz, 1871; San Marino, California, 1961.

KEVIN R. LOUGHLIN is a professor of surgery (Urology), Emritus at Harvard Medical School. He is a retired urologic surgeon.

Author’s note: “One of the many pleasures of living in Boston is being a member of the Massachusetts Historical Society. This unique resource goes far beyond its sui generis collections. Its annual lecture series provides an ongoing opportunity to be exposed to some of the best speakers and scholars of American history. Finally, the staff of the MHS are without equal in terms of their knowledge, courtesy, and insight.”

Winter 2019 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply