Mildred Wilson

|

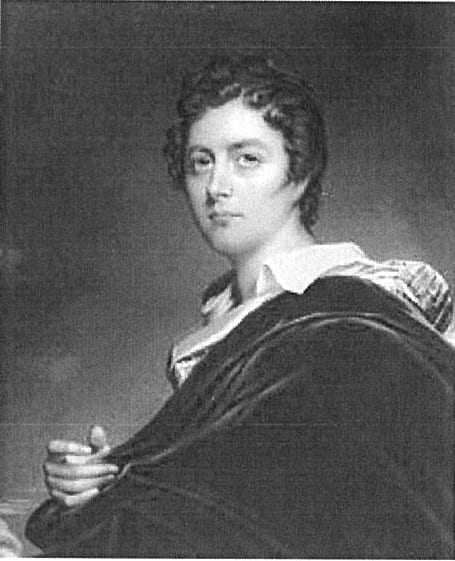

| Lord Byron (1837) by Henry Pierce Bone |

“. . . I would rather not exist than be large.” Lord Byron – Trinity College (1805-1808)

On April 15, 1805, George Gordon Byron wrote to Hargreaves Hanson, a fellow classmate at the prestigious school for boys Harrow, in conjunction with a planned visit to Hanson’s home: “. . . wish that you should forego the pleasures of contemplating pigs, poultry, pork, pease, and potatoes together, with other Rural Delights, for my Company.”1

For centuries, society has imposed its standards regarding the beauty of the human body. While these rules have created an emotional burden for women, they have also affected men, when, like women, they felt that the aesthetics of their bodies fell short. Lord Byron wrote to Hanson when he was seventeen. It was one of many incidents during Byron’s life in which he expressed concern about food.

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron, was born on January 22, 1788, son of Captain “Mad Jack” Byron, a British army officer, and his second wife Catherine Gordon, descendant of Cardinal Beaton and heiress of the Gight estate in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Catherine’s fortune was the attraction and Byron took Catherine’s last name to claim it. In short order, he squandered most of her fortune and left her with a small income and an infant son to raise. She moved to Aberdeen, where George spent his childhood.2 At the age of ten he inherited the English Barony of Byron of Rochdale, becoming “Lord Byron” and eventually dropping the double surname.

Byron was born with a deformity of his right foot, commonly known as a club foot. He went through a series of medical exams, but the doctors were unable to correct the problem. For the rest of his life he walked with a limp, which caused him psychological and physical misery.

From an early age Byron and his mother had a tempestuous relationship. They were always at odds and prone to name calling. As she ate and drank too much, Byron was disgusted by her and once stated, “I want to know why you eat so much. All the time eating, eating, eating and making yourself as fat as a sow.”3

Byron’s mother often called Byron a “lame brat” and accused him of thinking he was better than her.4 His mother’s taunts, more so than his peers’, hurt him the most. He became self-conscious to the point of nicknaming himself “the limping devil.” He often blamed his mother for his condition and accused her of wearing her corset too tight during her pregnancy, a speculation that he had overheard her doctor make.

Byron began his education at Aberdeen Grammar School. From 1799 to 1801 he was enrolled in the school of Dr. William Glennie in Dulwich Grove, under doctors’ supervision and advised to exercise moderately. In 1801 he enrolled at Harrow.5 To compensate for his disability, he became excessive about everything he tried, including ignoring his doctor’s advice.

In 1803, as young teenager, he fell deeply in love with Mary Charworth. His mother wrote, “He has no indisposition that I know of but love, the worst of all maladies . . .” Mary spurned him. He was so upset that he refused to return to Harrow in the fall term, but finally returned in January 1804.6

In August 1805, Byron was selected by Harrow to represent the school in its annual cricket match against Eton. He bragged that he had earned more “notches” than anyone else on his team. In that same year he visited Cambridge and entered Trinity College.7

|

|

| Lord Byron’s mother, Catherine Gordon, by Thomas Stewardson |

People in the eighteenth century were expected to look neat and elegant, and have a natural shape.8 Byron’s mother always made sure he wore nice clothes. While at Trinity, he was known to be excessive about his diet and to have a strange relationship with food. He was terrified of becoming fat, believing that it would result in lethargy and stupidity. He told friends that he would rather not exist than be large, routinely measured himself, and to keep his weight down often ate biscuits and drank soda water or potatoes drenched in vinegar. To further control his weight, he was known to wear six coats while exercising to sweat out excess water.9 He was five feet eight inches tall and his weight fluctuated between 133 and 200 pounds.

In 1808 Byron wrote his first volume of poems, Hours of Idleness. He received a negative review, but retaliated with the satirical poem “English Bards and Scotch Reviewers.” This piece brought him his first literary recognition.10

In 1809 Byron took his seat in the House of Lords and traveled on a grand tour with John Hobhouse throughout the Mediterranean and Aegean seas. During this trip he wrote two cantos of “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage,” which centered around a young man’s reflections on travel in foreign lands.11 He published this when he returned to England in July 1811, and it received rave reviews, making him an overnight success.

Over the years he wrote to friends about his eating habits. He discussed being a vegetarian. He wrote about eating only biscuits and tea for a week. When he tried fish and drank buccillas, he became sick. On several occasions, he starved himself, stating, “I will not be the slave of any appetite. If I do err, it shall be my heart, at least that heralds the way.”12

Pressed by growing debts, Byron began seeking a suitable marriage. He met and married Anne Isabella Noel, nicknamed Annabella, in January 1815. In December 1815, Annabella gave birth to a daughter, Ada Lovelace. Byron’s continuing sexual escapades with actresses and others, and his bizarre behavior toward his half-sister Augusta Leigh, were unacceptable to Annabella, who left Byron and took their daughter. They were legally separated in March 1816. Byron left England and never returned.13

In 1816, Byron went to Lake Geneva, Switzerland where he befriended Percy Bysshe Shelley, a fellow poet. Shelley was a strict vegetarian. Byron adopted some of Shelley’s habits, which consisted of eating a thin slice of bread and tea (no milk or sugar) for breakfast and vegetables and water for dinner. He smoked cigars or chewed tobacco to appease his pangs of hunger.14

By 1822 Byron had starved himself into a poor state of health. Some historians speculate that the constant weight fluctuations may have taken a toll, prematurely wearing out his body. In 1824 he fell ill with a fever, possibly a relapse of malaria, and died. He was thirty-six.15

More than a century later, in 1935, Paul Ferdinand Schilder, an Austrian psychiatrist, gave a name to the albatross around Byron’s neck, calling it “body image.” Schilder studied the works of the German neurologist Carl Wernicke, English neurologist Sir Henry Head, and Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud. He combined what he learned and created his own formulation of the fundamental role of body image in man’s relation to himself, to his fellow human beings, and to the world around him. He published these formulations in a book called The Image and Appearance of the Human Body.16

Body image has been loosely defined as how humans view themselves in the mirror or in their minds, combining one’s own appearance and overall attitude toward height, shape, and weight. Body image may be negative or positive. Persons with a negative body image may feel self-conscious, ashamed, or assume others are more attractive. This low self-esteem causes them to fixate on altering their physical appearance, which may lead to eating disorders. On the other hand, a person with a positive body image celebrates and appreciates his or her body and does not associate it with self-worth.17

Lord Byron has been heralded as one of the greatest British poets. His poems remain widely read and influential. Although scholars like to titillate their readers with Byron’s sexual escapades, they fail to discuss a serious legacy: his eating habits. Byron’s harmful diets, which wavered between anorexia and bulimia, rubbed off on everyone around him, particularly on youthful, impressionable Romantics. They copied Byron’s vinegar and rice diet to get the fashionably thin and pale look.18

Today, Byron is referred to as the celebrity diet icon that helped kick off the public’s obsession with how celebrities lose weight.19 Moreover, his diet of vinegar and water, which he fashioned in 1820, leads a list of diets introduced during the twentieth century that continues today. Dieting is not new. The Greek word “diaita” meant a sensible, moderate way of living and had no specific reference to food.20 Later, it came to be associated with foods that are customarily eaten.21 “Diet” is now indicative of an all-consuming practice and desire to lose weight. It is a multi-billion industry that fails over 90% of dieters.22 One might be inclined to believe that Byron intuitively understood the fallacy of what he had been doing most of his life.

References

- Byron, Gordon. (author) and Prothero, R. (ed.). The Works of Lord Byron: Letters and Journals. Vol. 1, A Public Domain Book, 1898

- Romantic Circles. http://www.rcumd.edu/references/chronologies/byronchronology/1778-1800.

- Browne, Gretta. A Strange Beginning. A Kindle Seanelle Publication, Inc., 2015, page

- Ibid, page 20

- Ibid, page 25

- Romantic Circles, op. cit., 1778-1800.

- Romantic Circles, op. cit., 1801-1809.

- The Body According to the Eighteenth Century. http:www.phys.org/news/2015-12-body-18th-century.html.

- Lord Byron’s Obsession with Dieting. http://www.mentalfloss.com/article/78761/lordbyrons-obsession-dieting.

- Romantic Circles, op. cit., 1801-1809.

- Romantic Circles, op. cit., 1809-1811.

- Byron and Prothero, op. cit., page 264.

- Op. cit., 1814-1816.

- Byron and Prothero, op. cit., page 231.

- Lord Byron’s Obsession with Dieting. https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/78761/lordbyrons-obsession-dieting.

- Schilder, Paul F. The Image and Appearance of the Human Body: Studies in the Constructive Energies of the Psyche. Routledge, London, 1999.

- National Eating Disorders Association. What Is Body Image? http://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/body-image-0

- Lord Byron’s Obsession with Dieting, https://www.mentalfloss/com/article/78761/lordbyrons-obsession-dieting.

- Diets Through History: The Good, Bad, and Scary. https://www.health.com/health/gallery/0,,20253382,00.html.

- Mediterranean Diet for All. https://www.mediterraneandietforall.com/mediterranean-diet-the-origin-and-history.

- Diet Is Big Business, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/diet-industry-is-big-business/

MILDRED WILSON has a Masters of Teaching in Visual Art and a Doctorate degree in Curriculum Development and Administration. She is a former high school art teacher, elementary principal, and a deputy director/consumer advocate for the Michigan Legislative Service Bureau. She currently spends her time as a caregiver for her mother and writing fiction and nonfiction.

Leave a Reply