Yong Gabriel

Berlin, Germany

In memory of Daniel Chong (1965-2001)

|

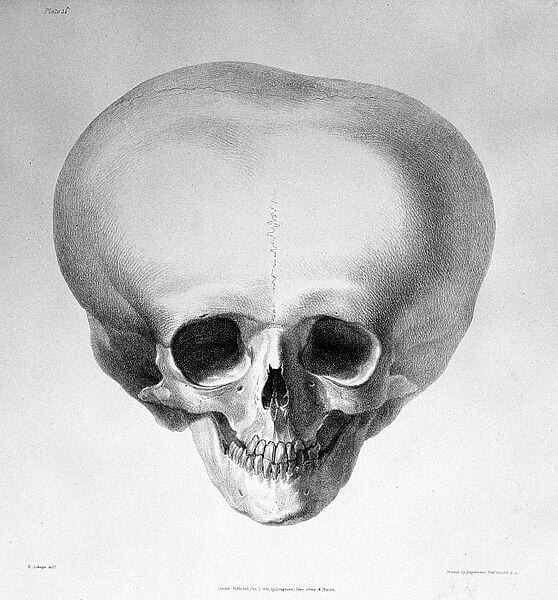

| A hydrocephalic skull, Richard Bright. Reports of medical cases selected with a view of illustrating the symptoms and cure of diseases by a reference to morbid anatomy (1827). Online source: Wellcome Collection |

My cousin Daniel was born in perhaps the most medically infelicitous era in human history. Developments in modern medicine ensured that he would survive serious congenital defects well into adulthood when barely half a century ago even many healthy babies did not make it past early adolescence. Alas, like my cousin, palliative care was also still in its infancy. The twentieth century witnessed millions of children like Daniel – individuals whose most remarkable event in life consisted of their miraculous survival at birth, only to be followed by a very dreary fadeout – as well as their noble but forgotten caregivers.

Daniel was the first child of Uncle Simon and Auntie Marie. Simon, like most of the men in the Chong family, worked as a civil servant in the state government. He had a fondness for gardening and stray cats (there were eleven in the house at one point), as well as questionable taste in ornamental fish (there was a large tank of illegal piranhas in the front porch). Marie, on the other hand, had been a nurse. After Daniel’s birth, she retired prematurely from the profession at the age of twenty and devoted the rest of her life to nursing her son.

According to family oral history, Daniel had hydrocephalus and severe muscular dystrophy. Though he successfully underwent a risky procedure to remove excess cerebrospinal fluid, the hydraulic pressure on his brain left him with a permanent conehead, profound intellectual disability, and complete speech impairment. His paraplegic state meant that he was perennially horizontal, while his sedentary existence contributed to his morbid obesity.

For the first three decades of Daniel’s life, Simon was the sole breadwinner of the family, until a stroke left him hemiplegic. Mirroring his son’s fate, he too became bed-bound until death. I am not sure if it was his hot temper (a pre-existing condition), his newfound state of constant physical pain, the neurological rewirings that sometimes alter one’s personality after a stroke, or his despair at the futility of it all; whatever it was, it transformed him into an abusive man. His semi-paralyzed mouth notwithstanding, he evidently retained sufficient control of his masticatory muscles to yell colorful Cantonese curses at his beleaguered wife every ten minutes.

For middle and middle-lower households with terminally ill and severely disabled persons across the world, the role of the primary caregiver inevitably falls on the stoic, gritty women of the family. Even in present-day Ipoh, institutional support and long-term professional medical care for the terminally ill or disabled remain a reserve for the affluent. Everyone else – from the Malay fruit-seller who home-schooled her child with cerebral palsy, to my mother’s colleague, who sterilized his retarded daughter because he would not be able protect her for the rest of his life – largely resign themselves to their stations in life as a private responsibility. Marie somehow managed to care for both son and husband on Simon’s meagre pension of RM600 (150 USD) a month.

As they resided less than five miles from us, my parents often hauled me along for evening visits. “Go and say hello to brother Daniel,” the adults beckoned whenever I arrived. Out of polite acquiescence and morbid curiosity, I would tread cautiously into the room at the end of the hallway.

With a smooth, pink complexion and a bloated, porcine physiognomy, Daniel looked like a gigantic thumb. His queen-sized bed filled the width of the room, which looked and smelled like a hospital ward. Marie, who was well aware of the importance of a sanitized environment for her son’s perpetually open wounds and maintained the ethos of her brief career, kept the space in pristine condition. There were no gadgets, no decorative elements, no toy rattle nor shiny strips of ribbon to mitigate his boredom. There were no wheelchairs or other assistive devices either; with a delicate frame of ninety pounds, Marie could not maneuver either man on her own. Here, within the confines of four barren, baby blue walls and windows facing a back alley, Daniel lived out almost all thirty-six years of his life without ever getting sun kissed.

Despite his verbal limitations, he was able to grunt and snort in response to our hellos and handwavings. Daniel clearly delighted in having visitors. I was never sure, however, if he knew who I was, much less remembered me. If he harbored an internal world of truncated communications and vivid imaginations, I could not access it.

Right next to the door, on the external side of the room, hung a quartz clock which ticked audibly. Did he recognize these soft pulsatings from the other side of the four-inch wall that separated him and the world beyond? If I had brought the clock to him, would he be startled by the mechanical and visual complexity of this strange instrument? And would he be able to strike a connection between the mysterious sounds that had plagued him all his life and this whirring device?

Did he even have a notion of time – that all motions and events, natural and man-made alike – proceed in some cosmic circadian rhythm? Or did the entire expanse of his life appeared to him as a single, indiscreet period without tempo or beginnings? If he had a rudimentary understanding of time, it must have been very different from the precision of our mathematical constructs.

To mark the passage of minutes, Daniel had songs and sounds emanating from the radio in Simon’s room. Radio advertisements typically last fifteen seconds, while pop songs average three–and–a–half minutes. If he was perceptive, he would also have discovered that the verse and chorus in the ABBA song structure that dominated the airwaves were of equivalent duration, corresponding to three-quarters of a minute each.

The hours would be marked by the tedious routines of his own physical maintenance. In spite of his mother’s round-the-clock efforts, Daniel developed large, foul-smelling bed sores that never healed. Pus needed to be expelled via a drainage tube regularly, or he would suffer horrendous infections. To prevent the development of new bed sores, Marie reconfigured his body at two-hour intervals. Too large and too immobile, his only means of a bath was a pail and a wet cloth, which was performed thrice a day. His diapers were changed as needed.

Daylight and night-time, of course, charted the passage of days. But there were other, more exciting indicators of the daily renewal of hubbub in a small town: the newspaper collector announcing to the quadrilingual residents, “Surat khabar lama! Old newspaper! 收旧报纸! Sau kau pou chi!” through his handheld speaker, and the ice-cream seller playing the theme of all Malaysian childhoods, “Paddle Pop, wow! Paddle Pop, yeah! Super duper yummy!” Both men pedaled daily across the neighbourhood, like clockwork, at about 4pm and 5pm respectively.

Last but not least, there was the Lunar New Year, which occurs at intervals of between 353 and 385 days. A cacophonous festival even by Chinese standards, the neighbourhood celebrations typically included lion dances accompanied by the crashing of cymbals and gongs, a racket of firecrackers and bottle rockets, and loud, jubilant music. From Daniel’s room, his soundscape would have been awash with din. In most years, all 50+ Chongs and their spouses gathered at Simon’s house on the second day of the festival. The younger cousins, per Chinese custom, would take turns to pay respects to Daniel. The congregation also represented the entire population of people in the world who knew of his existence. It was his day, and he loved it.

We knew that Daniel had remained the same bed for more than 300,000 continuous hours. From his perspective, however, time would have been measured on a somewhat different scale: there are approximately thirty-five songs per nappy change, three baths equate an ice-cream jingle and, every once in a long while – after too many blood-filled abscesses – he receives a whole room of companions.

Without Simon’s attention, the bougainvilleas wilted and the famished piranhas lost their bite. The cats, ever transactional in nature, left the house and regressed to ferality.

The first in a geometric succession of burials started with Simon, followed quickly by Daniel six months later. Marie looked perfunctory at both funerals; the capacity for animation had long been extinguished from her face. Her freedom was short–lived, however; we received the call just three months later that she, too, had died at the age of fifty–six. . There was much cynical debate among the relatives about who had suffered more: Daniel – because he could not imagine the life he had missed , or Marie – because she could?

I could not do anything to alleviate Daniel’s plight, because I was only a child when he died. Many years later, as an adult in the technology industry, I find myself living in a world of exponential timescales that is the diametrical opposite of Daniel’s quandary. It feels as though so much is happening so quickly that I am unable to grasp the profound implications of our socioeconomic and technological zeitgeist. My hope is that as emergent technological innovations and the march towards the better angels of our nature converge, we will create freer, more fulfilling, more participatory, more humane living conditions for the likes of Daniel and Marie, that they may not be mere passive subjects of the four miseries,i but the active authors of their own life and times.

References

- The “four miseries” is a reference to “birth, senescence, illness, and death”, whom the Chinese regarded as the inevitable and miserable sequence of life.

YONG WEI GABRIEL, BA, was born in Malaysia and works as a data analyst at the Berlin-based classical music streaming service IDAGIO. In her spare time, she plays the cello, powerlifts, and dabbles in digital photography. She has a degree in Philosophy from Wellesley College.

Winter 2018 | Sections | Personal Narratives

Leave a Reply