Lisa Mullenneaux

New York City, New York, United States

|

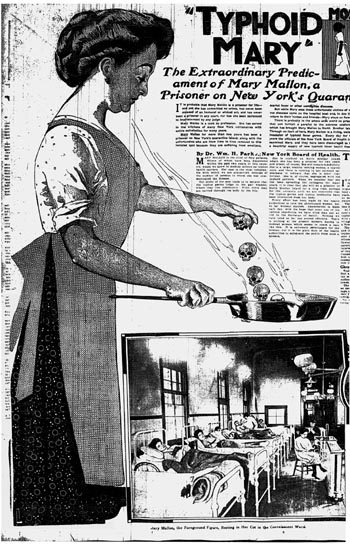

| Illustration from The New York American, 1909 |

The Irish cook who infected at least forty-eight people with typhoid bacilli, three of whom died, had a surname and a history, but Americans remember her only for her germs. Mary Mallon’s physical stamina and quick wits had served her well as an immigrant struggling to survive Manhattan’s Lower East Side; they also helped her avoid capture, leading health authorities on a dogged five-year chase. Mallon’s service to her adopted country as the first documented case of a “healthy carrier” of a communicable disease was small comfort to a woman confined to New York’s North Brother Island for twenty-three years until she died in 1938.

Sanitation expert turned epidemiologist, Dr. George A. Soper took credit for tracking down the woman he called a “human culture tube,” but Soper was not the person Mallon blamed for her captivity—and vowed to kill. That person was Sara Josephine Baker, a pioneer of public health programs at a time when dysentery, smallpox, and typhoid were common killers, especially among young children. Baker achieved many firsts. She was the first woman to head the city’s new Bureau of Child Hygiene in 1908; the first woman to earn a doctorate in public health in 1917 from New York University and Bellevue Hospital Medical College (today NYU School of Medicine); a woman who pioneered preventive medicine among the city’s neediest families.

But in 1907, as she tells her story in Fighting for Life, Baker was thirty-four and had just been given the title Assistant to the Commissioner of Health. In reality she was a “troubleshooter;” what no one else wanted to handle fell to Baker. It was Baker, for example, who vaccinated the bums in Bowery flophouses against smallpox at night when they were sleeping off the effects of cheap whiskey. And it was Baker that Soper assigned to collect specimens from Mary Mallon, without warning her that Mallon had already chased him away twice.

In 1907 Mary Mallon was forty years old and proud of her cooking and her physical strength, both of which she had needed to survive precisely the harsh conditions that Baker was working to improve. Mallon saw herself as someone trying to earn an honest living. The New York Department of Public Health saw her as the agent of a series of epidemics she could have prevented had she washed her hands more carefully or given up handling food.

Soper, who had a reputation as a “typhoid detective,” had traced her employment all over the Northeast from Maine to Oyster Bay. She never stayed long after typhoid began taking its toll on her clients. At the time, most people (and doctors) assumed it was the sick who spread diseases. But Soper was convinced of Dr. Robert Koch’s theory that infectious bacilli can remain dormant in a carrier’s body, producing no symptoms. In other words, a person might have typhoid and never even know it. Mallon insisted with “maniacal integrity” till she died that she had never contracted typhoid fever.

Using tips from employment agencies she had worked for, Soper finally caught up with Mallon in the service of a prosperous Park Avenue family whose daughter was dying of typhoid fever. Dr. Baker was assigned to get specimens of her blood and urine—a seemingly simple task. But that simple request was, for Mallon, a declaration of war: “Her jaw set and her eyes glinted and she said ‘No,’” recalled Baker. “She said it in a way that left little room for persuasion or argument.”1

That night Baker got a call from her supervisor Dr. Bensel instructing her to be at the corner of Park Avenue and E. 67th St. at 7:30 the next morning. When Baker arrived, she was met by an ambulance and three policemen who had orders to take Mallon into custody, by force if necessary. Battle lines were drawn for a supreme contest of wills.

The date was March 20, 1907. Baker positioned one policeman around the corner, another in front of the house, and kept the third with her as she knocked at the basement door. Mallon was ready, brandishing a carving fork. She lunged for Baker and then vanished. Completely. None of the staff would admit to having seen her and a three-hour search turned up no clues.

Except that a chair was set against the back fence separating two houses with suspicious footprints in the snow. “Much to the bewilderment of its occupants,” Baker writes in Fighting for Life, “we searched that house, too; but still no Mary.”2 Baker phoned her superior and was told to get Mary’s specimens—period.

On her return to the stakeout, Baker wisely recruited two more policemen and the search began again, for two more hours. Just as they were about to give up for the second time, a policeman spotted a scrap of blue calico caught in a closet door under the outside stairs leading to the front door. Mary’s co-conspirators had piled a dozen filled ashcans in front of the door. And when it was opened, Mallon came out cursing and swinging. She was innocent; the law was persecuting her; she knew her rights.

Baker watched as five policemen hoisted Mallon into the ambulance, kicking and screaming; then Baker sat on her all the way to Willard Parker Hospital. Baker remembers, “It was like being in a cage with an angry lion.”3 Her bad behavior had been Mallon’s undoing because had she agreed to let Baker take only urine and blood samples, she would have been a free woman. Hospital tests found bacilli only in Mallon’s feces.

Nor would Mallon agree to Soper’s suggestion that they remove her gall bladder, the probable site of infection. “I supposed that she would be glad to know the truth,” Soper wrote of his attempts to help her, “and to be shown how to take such precautions as to protect those about her against infection….”4 The doctor was not alone in his naivete. In 1910 Mallon was released by a new commissioner of public health, Dr. Ernst J. Lederle, who trusted her to report to him every three months and to quit cooking as a trade.

No sooner was Mallon out the hospital door, but she vanished again—to cook and to kill. It would be five years before an outbreak of typhoid at Sloane Hospital for Women, a maternity hospital in midtown Manhattan, allowed Soper and his team to arrest her for the last time. She died alone on North Brother Island, “a guest of the city,” but not before promising that if she could escape she would kill Baker, the woman who had outwitted her.

And her nemesis? Josephine Baker left a remarkable legacy when she died in 1945. She continued to combat disease caused by poverty and ignorance as the first woman to represent the U.S. to the League of Nations when she served on its Health Committee. Her work launched the Federal Children’s Bureau and Public Health Services (now the Department of Health and Human Services), and child hygiene departments in every state. She served as president of the American Medical Women’s Association and wrote 250 articles (for both the professional and popular press), four books, and her autobiography. Yet when she sat down to document these trailblazing feats, they looked like child’s play—compared to facing down Mary Mallon.

References

- S. Josephine Baker, Fighting for Life, New York: Arno Press, 1974, p. 73-74.

- Ibid., p. 74.

- Ibid., p. 75.

- George A. Soper, “Typhoid Mary,” Military Surgeon, vol. XLV, No.1, July 1919, p.10.

LISA MULLENNEAUX, is a Manhattan-based journalist and poet, who teaches writing for the University of Maryland. Her poems and stories have appeared in Stone Canoe, 4Rivers, American Arts Quarterly, and the New England Review. She maintains the art poetry blog paintersandpoets.com.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Summer 2016 – Volume 8, Issue 3

Summer 2016 | Sections | Infectious Diseases

Leave a Reply