Peter Kopplin

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

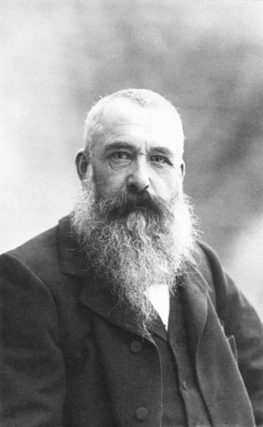

In January 1923, the elderly artist Claude Monet struggled restlessly in his room after his cataract surgery. He got up and tore at his bandages.1 His family put it down to his temperament. But an elderly man in his eighties, immobilized, recovering from surgery with limited sight in the left eye and bandages over the right eye, is a culture dish for delirium.2 Because he was a heavy smoker, there was even the added possibility of nicotine withdrawal.

Monet had resisted having his cataracts operated on for many years. Was this stubbornness in the famous Impressionist or were there reasonable grounds for his decision? In 1907 he first began to have problems with his eyesight. Some experts feel that his Venice paintings show a blurring of distant objects.1

By 1912, at the age of 72, he was diagnosed with bilateral cataracts with the right being more pronounced. Cataracts were first detected as far back as 1908 while he was still vigorously painting.2 He had doubts about the diagnosis from his “country doctor.” Quite naturally Monet sought out other opinions and the variety of advice terrified him. He decided to put off any intervention.

As his cataracts matured, his sense of color changed and more reds and browns appeared in his paintings. Those of the lilies and Japanese bridge of his Giverny garden show an increasing use of browns and a softening of the edges of his objects. At the beginning, this was rather pleasing but later the paintings became blurred. He began to struggle more with his paintings, complaining of his inability to see color and form as he once did.

By 1918 he felt the colors lacked their previous intensity and he became discouraged. In 1919 his eyes were very troubling and his friend, the famous French political leader Clemenceau, suggested surgery. He resisted again.

Marmor devised a way of simulation in a study of Monet’s cataracts. He felt the surgery at the time was well established and relatively safe.3 Monet was of course worried about his color perception. He himself felt that his paintings were darker.

By 1922 his sight was so troublesome that on the friendly persuasion of his friend Clemenceau, he saw Dr. Charles Coutela, a prominent Paris ophthalmologist, who was a competent surgeon. Coutela’s examination showed that Monet’s right eye could only perceive light and his left eye had a visual acuity of 1/10.2

He recommended surgery but Monet, still reluctant, declined partly because he improved when mydriatics were administered to his left eye. Monet also knew that Daumier, a fellow artist, had done very poorly after his cataract surgery some years before. Another Impressionist, Mary Cassat more recently still had very poor results. Nevertheless, in 1923 Monet decided on surgery partly out of his personal distress but also because he was goaded on by his friend Clemenceau who was anxious that Monet complete a commissioned project of panels of water lilies for the French government to be placed in the L’Orangerie.4

Monet’s cataract surgery falls into the historical era when the method of treatment was removal, following the French surgeon Jacques Daviel’s successful extraction of a cataract in 1747. However, none of the lens replacements introduced in 1950 by Harold Ridley that marked the third era of cataract treatment was available to Monet.

The three-step procedure proposed by Coutela first involved the removal of a small fragment of the upper part of the iris. This was carried out at the Ambrose Pare Surgical Clinic in Neuilly. When he finally had step two, he was hospitalized at Neuilly again where his restlessness so disturbed his care that it set back his recovery. When the surgery was completed, his troubles were not finished. He struggled with the visual changes, initially seeing too much yellow and finding shapes difficult to see clearly. Coutela tried various lenses and glasses but nothing seemed to help much and Monet grew increasingly depressed. A third procedure followed in February. Monet then began to complain that objects curved abnormally and the colors were strange. With the glasses that had been provided he feared falling, noted double vision, and described objects as deformed.

By July 1923, roughly six months after his initial surgery, the posterior lens capsule became opaque, a complication that disappointed Monet but was expected by his surgeon.1 It suggests that Coutela had not been entirely frank about this possibility. In July he removed the capsule in his home at Giverny. Monet had difficulty with the new glasses he now had to wear. He felt that he still saw everything too yellow (xanthopsia).

However, by the fall of 1923, he was painting again after turning down surgery on his left eye. By the summer of 1924, blue had replaced yellow as the dominant color in his vision. This unusual phenomenon may have been because with the removal of his yellow lens his aphakic eye saw blues once again. Another explanation by some is that without the lens his eye could now see ultraviolet light, which has been suggested to be a whitish blue.4 In addition to seeing things too blue, he had difficulty focusing at various distances. The spherical shape of the lenses and chromatic aberrations would give a visual distortion. Ravin, the American ophthalmologist who gained access to the glasses he used, felt that after examining them Monet would have this difficulty along with the aberration of shapes that he described. Modern intraocular lenses and contacts overcome this.

Then like Job’s friends, there appeared on the scene new faces. Andre Barbier, a painter friend, introduced him to another ophthalmologist, Dr. Jacques Mawas, and an oculist, M. Denis. Barbier had discovered the availability of a revolutionary set of Zeiss lenses available and he thought Coutela was out of his depth with them. After several trials Monet seemed to gain at least some partial help.

At the beginning of 1925, Monet’s confidence had withered. He proposed giving up his government commission but after a charged exchange with Clemenceau, he recovered enough to return to painting and he completed several of the panels for the work in the L’Orangerie before he died.

Unhappily he began to develop a cough and by the spring of 1926, he was quite weak and losing energy. In September, the diagnosis of lung cancer was made by x-ray and he succumbed to his illness on December 5, 1926. Family and friends kept the diagnosis from him.

From the standpoint of the understated miracle of today’s cataract surgery, it is easy to question Monet’s resistance to operation. However, recognizing the importance of his vision to his lifetime work and the harsh experience of his friends, it is more understandable. One can only speculate as to what would have happened if he had been able to avail himself of modern surgery and intraocular lenses. Quite likely he would have been able to return with vigor to his painting at a much younger age and without the emotional drain of wrestling with different lenses and glasses for his postoperative symptoms.

References

1. Wildenstein, D. Monet or the Triumph of Impressionism. Taschen; 1996.

2. Ravin J. Monet’s Cataracts. JAMA July 19, 1985; 254 (3): 394-399.

3. Marmor MF. Ophthalmology and Art: Simulation of Monet’s Cataracts and Degas’ Retinal Disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006; 124(12):1764-1769.

4. Sagner, K. Monet. Los Angeles: Taschen; 2001.

5. http://www.theguardian.com/science/2002/may/30/medicalscience.research accessed December 11, 2014.

6. Tucker, PH, Shackleford, GM., Stevens MA. Monet in the 20th Century. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1998.

PETER KOPPLIN is a practicing internist in Toronto and a member of the Toronto Medical Historical Club, which has been meeting since 1923.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Winter 2017 – Volume 9, Issue 1

Leave a Reply