Rebekah Abramovich

New York, New York, United States

Innovations in medical technology emerge at times from unexpected sources. How does one document the larynx? The voicebox, as it is sometimes called, is the hollow muscular organ that forms an air passage to the lungs and holds the vocal cords. The solution arose out of one man’s curiosity when an avid amateur photographer and tinkerer trained as a civil engineer suffered from an ailment of the larynx. George Bradford Brainerd (1845-1886) turned to the problem out of personal need and developed an elegant solution that constitutes the foundation of laryngeal photography in contemporary medicine.

A Tinkerer in Brooklyn

George Brainerd1 was born in Haddam Neck, Connecticut in 1845, moved to Brooklyn two years later, and spent most of his life as a Brooklyn resident. At the early age of sixteen, Brainerd trained as a civil engineer at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute of Troy, New York. The twenty-year-old graduate took a post as surveyor at the Brooklyn Water Works where he quickly rose to the position of Deputy Water Purveyor of Brooklyn by 1868. He remained in the position until his early death from a brain tumor at the age of forty-one in 1886.2

During his tenure as Deputy Water Purveyor, Brainerd published a dense volume entitled “Water Works of Brooklyn: A Historical Descriptive Account of the Construction of the Works, and the Quantity, Quality and Cost of the Supply.” Brainerd was also dedicated to life-long scholarship in a number of arenas outside his field of expertise such as linguistics, botany, geology, medicine, and photography. His interest in botany and geology led him to personally classify the moss and lichen collections at the Long Island Historical Society. He additionally learned to read in twelve languages.3

Most prescient, his life-long interest in photography was born at the age of thirteen. Even at that early age, Brainerd’s interest extended beyond the captured image. Instead, he was fascinated by the mechanism of the camera and the mechanical possibilities of the relatively new photographic technologies. Early on, Brainerd created his own cameras from cigar boxes and the lenses from opera glasses in order to create primitive ambrotypes.4

|

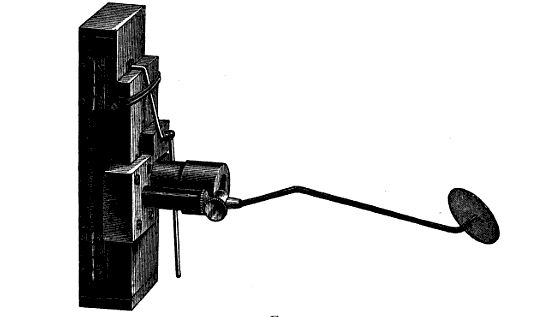

| Figure 1. Illustration of Brainerd and French’s laryngeal camera (French 1883) |

Freeze Frames

Brainerd was a founding and active member of the Brooklyn Academy of Photography. By 1870, though, Brainerd exited the familiar setting of the amateur photography club and brought his camera outside to document the landscape around him—predominately Brooklyn and Long Island. Monuments and architecture dominate most of Brainerd’s frames. Within the technological limitations of slow exposures as well as a large awkward camera and tripod, structures were an ideal focus.

Brainerd, however, wished to also photograph people moving throughout the landscape, and this presented a much more difficult technical task. The engineer wanted to capture motion as well as natural unrehearsed moments of action. He constantly tinkered with methods of ameliorating these issues.

He soon developed what he called a “slide box” camera that could capture a still image without the need for a steadying tripod. In order to speed up the exposure Brainerd developed his own chemical preparation for dry plates. In addition, he disguised the “slide box” as a pile of newspapers, allowing the photographer to sneak in for a shot without the subject’s knowledge. Next, Brainerd adapted the camera to be hidden inside of a book. In one device, he invented an early proto-type for the instamatic hand-held camera as well as the first spy camera.5

Adrieanne Martense, the Secretary of the Brooklyn Academy of Photography, was a close colleague of Brainerd. In an article published in the Brooklyn Eagle in 1886 that memorialized Brainerd’s many professional and photographic accomplishments, Martense reported that “the happiest moment of [Brainerd’s] life was when he developed his first successful picture . . . which was of a Chinaman walking with his foot off the ground.”6 Brainerd considered the ability to document motion as his highest accomplishment.

|

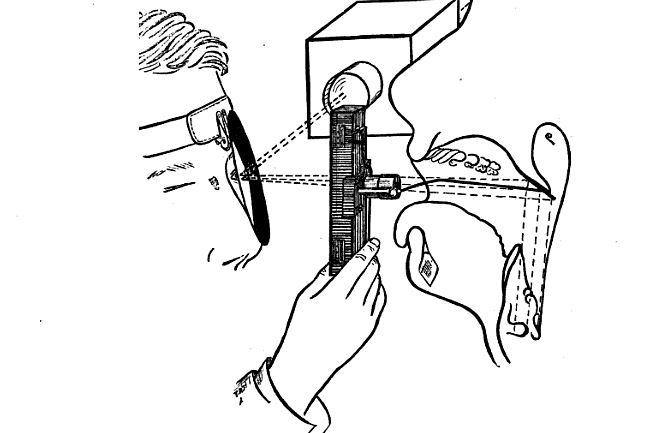

| Figure 2. Illustration of laryngeal camera setup (French 1883) |

Documenting the Ailment

Developing a camera to photograph the larynx was not a new idea in the 1880s. Several doctors and inventors had experimented, to little avail. Brainerd’s focus on the issue originated from a personal health matter. In 1882, Brainerd suffered from an abscess in his larynx that interfered with respiration.7 His interest in laryngeal documentation was personal.

Brainerd visited Dr. Thomas R. French, laryngoscopic surgeon at Brooklyn’s St. Mary’s Hospital and Professor of Laryngology and Diseases of the Throat at the Long Island College Hospital Medical School. After Dr. French incised the abscess, Brainerd turned his engineer’s eye to the broader issue: how might a doctor, or even a patient, examine and document the larynx and its movements?8

Dr. French and George Brainerd balanced one another well in seeking out an answer to the question. Whereas Dr. French provided the medical expertise, Brainerd brought his skill of adapting traditional camera mechanisms to the table. Within a year and after over 2,500 unsuccessful attempts, Brainerd and French successfully photographed a larynx. A view camera, the predominant photographic mechanism of the time, was too ungainly for the purpose. The two men developed a hand-held camera the size of a cigar box with a drop shutter and attached mirror which resulted in instantaneous exposures and access to a throat.9

The photographs were ridden with issues of exposure, however; not to mention that the patient had to “pose” for the camera in an awkward and uncomfortable position for prolonged sessions. The results were flawed but the message was clear: the impossible was now possible and only needed to be refined. As Dr. French wrote for the American Laryngological Association in 1882, “My object in presenting these comparatively unsatisfactory photographs to the association is solely to prove that it is possible to photograph the larynx.”10

|

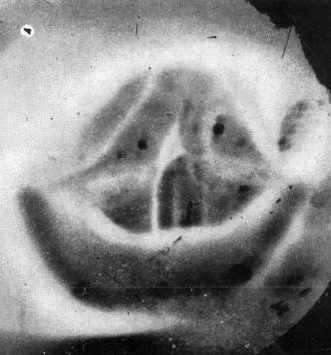

| Figure 3. Successful photograph of larynx by George Brainerd, 1884 (Caruso 1952) |

By 1884, French and Brainerd had honed the process into a simple and elegant system and presented their results at the International Medical Congress in Copenhagen to rave reviews. They had thoroughly experimented with the illumination process, utilizing sunlight, condensed light, oxyhydrogen, magnesium, and electric lights. Brainerd preferred to use natural light and created an accessory to the camera that he called a “sunlight concentrator,” which captured and redirected a strong illumination from available sunlight. Unlike electric or magnesium illumination, the sunlight concentrator did not create extant heat, which could disturb the photographic emulsion at close range. With the powerful light, the doctor was able to take faster exposures, creating five plates in ten minutes.11

Dr. French and George Brainerd made sure that their process could be easily reproduced by any doctor, even one unfamiliar with cameras. Their technique was refined so that it would only take a doctor five minutes to set up the camera and accessories and not more than ten minutes to photograph the patient, making the process appealing to a wide range of practitioners.12

The resulting documents of the larynx could take a number of forms adaptable for a variety of situations. For instance, the plates could be developed and then processed into enlarged photographic prints for close-up examination. The plate could also be placed on a projector and used as in a classroom situation at a medical school or conference. Finally, the plate could be transferred to a black background for a wood engraving that could then be reproduced or published, not to mention it is then easier to store.13

Brainerd did not patent his photographic innovations or seek to spread or reproduce his early innovations to the public. He created a wide range of handheld and spy cameras long before this type of photographic mechanism existed in the technology’s literature or market. Brainerd, however, used these tools to satisfy his visual and mechanical curiosity. They only existed within his personal sphere, sharing the results with his family and camera club. In partnering with Dr. French, though, Brainerd’s laryngeal camera was brought before an international audience and its importance was instantly recognized and used by the contemporaneous medical field.

Figures

- Figure 1.

- Figure 2.

- Figure 3.

Notes

- George Brainerd’s name is often spelled Brainard. The spelling alternates across newspaper coverage, scholarly papers, and legal documentation.

- Lucy Abigail Brainard, The Genealogy of the Brainerd-Brainard Family in America vol. 2 (Hartford: Case, Lockwood and Brainard Company, 1908); Phoebe Neidl, “Hidden Camera Snapped Photos of Old Brooklyn,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle (27 March 2009).

- Brainard; Neidl.

- Brainard; Neidl; “Memorial Reminiscences of the Late George B. Brainard,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle (23 June 1887).

- Brainard; Daily Eagle (1887).

- Daily Eagle (1887).

- Dr. Thomas R. French, “On Photographing the Larynx,” Transactions of the Annual Meeting of the American Laryngological Association (1883): 60.

- Dr. Thomas R. French, “On Photographing the Larynx,” Transactions of the Annual Meeting of the American Laryngological Association (1883): 60; Dr. Thomas R. French, “Photographing the Larynx,” The Dublin Journal of Medical Science vol. 82 (1886): 498.

- French (1882); T. Anthony Caruso, “Photographing the Vocal Chords,” IMAGE: Journal of Photography of the George Eastman House vol. 1, no. 7 (October 1952), pp. 3-4.

- French (1882).

- French (1883); Caruso, 3; Dr. Frank Foster, Ed., “Photographing the Larynx,” International Record of Medicine and General Practice Clinics vol. 44 (6 November 1886): 520.

- Foster, 520.

- French (1886).

References

- Brainard, Lucy Abigail. The Genealogy of the Brainerd-Brainard Family in America vol. 2 (Hartford: Case, Lockwood and Brainard Company, 1908).

- Caruso, T. Anthony. “Photographing the Vocal Chords,” IMAGE: Journal of Photography of the George Eastman House vol. 1, no. 7 (October 1952), pp. 3-4.

- Foster, Frank. Ed., “Photographing the Larynx,” International Record of Medicine and General Practice Clinics vol. 44 (6 November 1886): 520.

- French, Thomas R. “Photographing the Larynx,” The Dublin Journal of Medical Science vol. 82 (1886): 498.

- French, Thomas R. “Photographing the Larynx,” Scientific American: Supplement vol. 19-20 (New York: Munn and Company, 1885), pp. 7555.

- French, Thomas R. “On Photographing the Larynx,” Transactions of the Annual Meeting of the American Laryngological Association (1883): 60.

- French, Thomas R. “On Photographing the Larynx,” Archives of Otolaryngology vol. 3 (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1882), pp. 222.

- “Memorial Reminiscences of the Late George B. Brainard,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle (23 June 1887), pp. 1.

- Neidl, Phoebe. “Hidden Camera Snapped Photos of Old Brooklyn,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle (27 March 2009).

REBEKAH BURGESS ABRAMOVICH, PhD, is currently working on a grant-funded project in the Jefferson R. Burdick Collection in the Department of Drawings and Prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She previously worked at the LIFE Magazine Photography Collection (LPC), the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Abramovich received her PhD in American Studies focusing on Photographic History from Boston University in 2008.

Leave a Reply