Silvia Maina

Editamed, Torino, Italia

|

| Figure 1. D. O. Hill and R. Adamson: Woman with a goitre. |

Since its introduction, photography has found an application in medicine. Many physicians embraced the potential of this technology as a valued adjunct to patient care, research, and education.

Medical photography dates back to the mid-nineteenth century, a few years after the birth of modern photography. The first application of photography to medicine appears to be in the field of photomicrography: in the mid-1840s, Alfred François Donné, a French physician and cytologist, published a photomicrograph atlas depicting medical specimens.

The earliest medical portrait of a patient is a calotype of a woman with a large goiter taken in ca.1847 in Edinburgh by the Scottish photographers David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson (Figure 1).1 Hill and Adamson opened the first photographic studio in Scotland. They mainly produced classical studio portraits of people amongst the different social classes and professions. The “woman with goiter” calotype was created according to the specific set of conventions used in that period in paintings and drawings for portraits and domestic scenes. The woman is photographed on a dark background, she is clearly recognizable, and her social class can be deduced from her dress.

Even if photography was considered from the very beginning as a tool to objectively document a patient’s disease or condition, the first images still showed a sort of artistic interpretation and were more like portraits than clinical documentation. In many of these images, the scene may also include the presence of hospital staff, who held or touched patients, and the appearance of the disease was not the principal subject of the photograph.

Hermann Wolff Berend, founder of a Berlin orthopedic clinic, and Hugh Welch Diamond, a British psychiatrist, are considered to be the first consistent users of photography within medicine in the early 1850s.1 In 1852 Berend applied photography to orthopedics, taking pre- and post-treatment images. His collection contains hundreds of photographs which combine both portrait and clinical conventions.2

Diamond gathered a collection of psychiatric portraits to evaluate the so-called “insane” and his portraits were reproduced in medical journals. He combined his medical expertise with photographic training (he was one of the founder members of the Photographic Society) and was one of the first clinicians to use photographs for different purposes: to evaluate physiognomy, to diagnose the disease, to present case reports, and to show the progress of treatment. He also shared his pictures with his patients as a part of therapy, because he believed that accurate self-image could force them to recognize their illness.3 In his words, “The photographer needs in many cases no aid from any language of his own, but prefers to listen, with the picture before him, to the silent but telling language of nature.”4 His patients were photographed in simple poses, and final images were very similar to conventional studio portraits of the time. They were also shown in photographic exhibitions, but visitors and reviewers were unsure how to consider them, being “neither art nor science.”

From skin diseases to war trauma, psychiatry, tropical infections, and orthopedics, clinical photographs were increasingly used to record disease progression, rare diseases, and medical techniques.

In 1865, Alexander John Balmanno Squire, chief of surgery and medicine for the British Hospital for Diseases of the Skin in London, published the first photographic atlas of dermatological diseases, entitled Photographs (colored from life) of the Diseases of the Skin. In his introduction, Squire wrote: “The great difficulty hitherto experienced in producing illustrations adequately portraying the various diseases of the skin, induced me to try if greater accuracy and more lifelike representations might not be obtained by means of photographs of the disease colored from life by one of the best artists.”5

In 1862, in France, Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne de Boulogne published L’Electrisation Localisée, a huge iconographic work with accompanying text that is considered the first publicly published volume of photographs of clinical material. Duchenne, thinking that each emotion had its own specific facial muscle, used faradic stimulation to stimulate the facial muscles and photography to record their actions.6

|

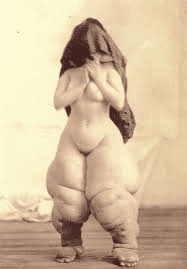

| Figure 2. G.H. Fox and O. G. Mason: Woman with elephantiasis |

In America the use of the daguerreotype was much more popular than in Europe. Gurdon Buck, considered a pioneer plastic surgeon during the Civil War, was the first surgeon to incorporate a preoperative photograph of his patient into an article in 1845. This daguerreotype was taken to record the appearance of his patient before and after the surgical operation.1

A significant new development in clinical photography came about when a photographic department was established within a hospital. In New York City, the first medical photography department was established by Oscar G. Mason at Bellevue Hospital.1 Mason promoted the use of photography in the medical profession. He also helped to uphold photography’s legitimacy and reliability, seeking to promote it as a scientific and objective technology, and the photographer as an honest and trustworthy professional. One of his most significant images is the so-called “Bellevue Venus” (Figure 2). It shows a woman with elephantiasis of the legs. The woman is naked but has cloth draped over her head, probably to protect her privacy.

In Paris, the neurologist J. M. Charcot created the Photographic Service Laboratory at the Clinic for Diseases of the Nervous System at the Salpêtrière Hospital. Charcot’s clinical method was based on close observation of his patients, and photography was considered an objective method to improve this observation. Charcot was also conscious of the educative usefulness of photography, and he was among the first medical teachers to use a slide projector to share photographs during lectures.7 Photography was incorporated in the everyday activity of the hospital. Since doctors could not predict when or where a seizure attack was going to happen, photographs of patients were taken in bed to try to capture an attack when it happened. Others were taken outdoors, as the procedure required a good light source to avoid long exposure time and blurring occurred if the patient moved quickly.

When Albert Londe became the director in 1882, some changes were implemented. He stopped photographing patients in the bed or the garden and concentrated in developing the photographic studio. Londe’s innovations were described in his La photographie médicale.8 The book, entirely dedicated to medical photography, aimed at systematizing photographic production. It provided a detailed discussion of the best photographic materials to use, as well as the most suitable orientation of the rooms in which the photos were taken, with advice on how to build a stage and possible background colors.

Nowadays it may seem obvious that a medical photographer must not only possess a broad knowledge of the photography process together with a good knowledge of anatomy, physiology, and histology, but also a deep sensitivity to the patient’s condition and state of mind. Clinical photography must respect a patient’s privacy and tact should be exercised to provide safety and dignity during the photographic procedure. This was not true for the very early days of clinical photography.

Most clinical collections before the 1950s lacked any kind of attention to the patients’ privacy. Although there are some documented cases in which doctors sought permission for publication of the patient’s photographic materials, in most cases no consent was asked, especially with patients from a lower status. In only a few cases was a sheet or cloth used to mask the identity of the patient.

Privacy precautions started to increase at the end of the nineteenth century. With the introduction of the Kodak hand-held camera in the 1880s, considered to be the starting point of amateur photography, a debate among physicians emerged on the popularity and real meaning of medical photography. They argued that patients were too often exposed to photographs that were sometimes taken unnecessarily. In a letter to the editor in The New York Medical Journal, a reader started a debate on “indecency in photography,” writing that “The truth is, it seems to us, that photography is too much used in medical illustration, quite apart from considerations of decency and of the rights of the patient. […] The most humiliating thing of all about the rage for photographic illustrations, lies in the undeniable fact that many writers resort to them mainly to support their statements, to establish their veracity.”9 Besides, “the scope of the photograph should be confined to the parts in which the phenomenon noted occurs; that the rest of the body, being unnecessary to the demonstration, be left out of the field, or be suitably covered up.”9

This lead to the creation of some of the rules and standards that are still followed today in clinical photography. Photographers began not only to make patients anonymous and eliminate indications of social class, but also omitted parts of the body which were not diseased from the frame.

In the twentieth century a clear distinction emerged between portraiture and clinical photography, which was supposed to be objective and not artistic nor creative. The rapid proliferation of photographic technology corresponded with the establishment of medicine as a science and a profession.

References

- McFall KJ. A critical account of the history of medical photography in the United Kingdom. IMI Fellowship Submission; 2000.

- Hannavy J. Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. London: Routledge; 2008.

- Pearl Pearl S. Through a Mediated Mirror: The Photographic Physiognomy of Dr. Hugh Welch Diamond. History of Photography. 2009;33(3):288-305.

- Diamond HW. On the Application of Photography to the Physiognomic and Mental Phenomen of Insanity. London: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London; 1856.

- Squire AJB. Photographs (coloured from life) of the diseases of the skin. London: J. Churchill and sons; 1864-1866. http://www.artandmedicine.com/biblio/authors/Squire.html

- Parent A. Duchenne De Boulogne: a pioneer in neurology and medical photography. Can J Neurol Sci. 2005;32(3):369-77.

- Didi-Huberman G. Invention of Hysteria. Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière. Cambridge: The MIT press; 2003.

- Londe A. La photographie médicale. Application aux sciences médicales et physiologiques. Paris: Gauthier-Villars et fils; 1893.

- Letters to the editor: Indecency in photography. The New York Medical Journal. 1894;59:724-25.

SILVIA MAINA has a degree in pharmaceutical chemistry and works in the medical publishing field, assisting clinicians in the creation of editorial projects. She is a member of the Editorial Board of the European Science Editing (ESE), the journal of the European Association of Science Editors. She is an amateur photographer and has always been intrigued by the connection between photography and science.

Winter 2018 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply