Bernardo Ng

San Diego, California, United States

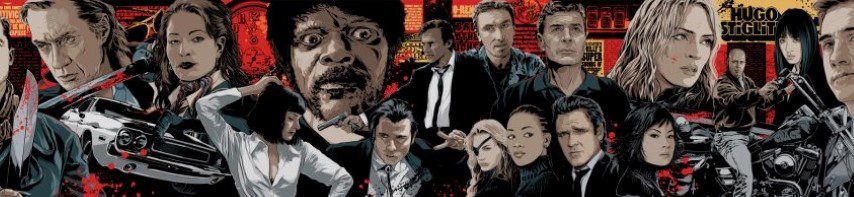

Cinema as an educational method for psychiatric trainees, medical students, and other mental health specialists has been successfully used for decades. Films portray mental illness and mental health problems in a variety of ways. Watching a film can be useful when learning to examine a patient, reach a diagnosis, identify personality disorders, and understand doctor-patient interactions. In the particular case of antisocial personality disorder, its comorbidities with other personality disorders, as well as differentiating criminal behaviors not associated to antisocial personality disorder, are powerfully depicted in Quentin Tarantino’s movies.

Tarantino, actor, director, and screenwriter, has developed a broadly recognized career in the art of cinema. He has been nominated and awarded by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, the Cannes International Film Festival, and the Golden Globe Award among others. Born in Tennessee in 1963, he has distinguished himself for the last 20 years in a hard to define movie genre that falls somewhere in between crime, fantasy, action, and fiction.

He has been both renowned and criticized by the degree of violence used in his movies. In fact, it is so extravagant that it often transcends the credible. For example, some scenes depict a lead character taking on dozens of samurai trained assassins at a restaurant, a former slave taking on more than thirty plantation guards with only two revolvers, an undercover cop bleeding out of his abdomen for hours without entering into hypovolemic shock, or two mobsters shooting incessantly without running out of bullets.

Distant from the charming, aggressive, callous, and extraordinarily intelligent sociopath frequently found in other movies, Tarantino offers a great variety of characters, with different “shades of meanness.” His characters are more real life in terms of fulfilling established clinical diagnostic criteria, such as selfishness, deceitfulness, irritability, impulsiveness, lack of altruism and social concern, irresponsibility, incapacity for mutually intimate relationships, use of dominance and manipulation, lack of empathy, and great propensity to take risks.

As for the violent and criminal acts, he is able to illustrate a myriad of characters with differing motivations: from the pure psychopath who kills for no reason, to an actress turned spy who kills to save her own life, a movie theater owner who sacrifices herself in order to kill Hitler and his high rank officers, a Chinese martial arts master who trains professional assassins, a dentist who converts into a bounty hunter, or an abused girl who becomes the leader of all the Japanese underworld families. Portraying in some cases how humans in the right, or rather, wrong environment may be compelled to execute criminal acts even without having an antisocial personality disorder.

Besides the violence, Tarantino has managed to present stories with clever dialogues, racial and ethnic overtones, obscene language, and spectacular if not fantastic locations, such as an old chapel in El Paso, Texas, an old and empty warehouse in Los Angeles, colorful gardens somewhere in Southeast Asia, a movie theater in Paris, a restaurant filled with Hollywood icons, and a southern plantation.

At the end of the day, a pervasive message in Tarantino’s stories is the possibility to “change” the antisocial personality, behaviors, or tendencies. This question, which remains clinically unanswered, is carefully addressed in every one of his movies. It is very interesting how predators in one part of the movie can become prey and vice versa towards the end of it. In fact, a distinctive feature in every one of his movies is that the meanest character ends up seriously hurt or killed.

Properly identifying a patient with antisocial personality is of particular importance for all clinicians in the mental health arena, and perhaps even more important for physicians not specialized in this field. The presence of this diagnosis can worsen the prognosis of psychiatric and non-psychiatric conditions.

Tarantino has carefully crafted a style from which moviegoers in the medical field can learn a lot, especially from the dialogues, wording, non-verbal language, tone of voice, and every gesture of his characters. Once you go beyond the violent acts, the streaks of blood, and the body dismemberment, watching Tarantino movies can be of extreme use for all students of the human psyche.

References

- Bugra Dinesh. Teaching psychiatry through cinema. Psychiatry Bulletin. 2003;27;429-430.

- Hyler SE, Moore J. Teaching psychiatry? Let Hollywood help! Suicide in the Cinema. Academic Psychiatry. 1996;20;212-219.

- Fleming MZ, Piedmont RL, Hiam CM. Images of madness: Feature films in teaching psychology. Teaching of Psychology. 1990;17(3);185-187.

BERNARDO NG, MD, DFAPA, is Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego. He is co-founder of the Sun Valley Model integrating clinical, teaching, and research activities with collaboration of private and community clinics, industry, and academic centers. He works in one of the poorest counties in California, covering a rural and underserved area of predominantly Hispanic population on the Mexican border. His research focus includes rural issues, antipsychotic use in the elderly, and behavioral disorders in dementia.

Leave a Reply