Chloé M. DeLisle

Colombia

Photography by Chaostrophy

The taking of the Hippocratic Oath is an oral tradition that encourages the participants to feel a continued commitment to a professional set of values and ethics.1 By invoking the gods it also creates a divine link, reinforcing the physicians’ responsibility to uphold a sacred tradition and binding them to each other and to their shared craft, with the audience as witness to their pledge. Taking the oath reinforces the physicians’ sense of honor and responsibility to uphold the values of their profession.

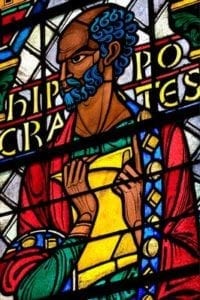

The Hippocratic Oath is part of a collection of some sixty Greek medical texts, the Hippocratic Corpus, associated with the 5th century BC physician Hippocrates of Cos.2 Hippocrates is most famous for curing a Macedonian tyrant of love sickness, refusing gold to serve the enemy king of Persia, and for driving the plague out of Athens in the 5th century BC. The medical achievements in these legends reinforce the theory that Hippocrates was actually an Aslepiad,3 a descendent of the Greek god of medicine, Asclepius. According to 2nd century philosopher Celsus, Hippocrates had eloquence as well as knowledge,4 representing “the ideal physician ‘who with purity and with holiness lived his life and practiced his art.’”5 It is this persistent perception of medical achievement, honor, and integrity that grants the Hippocratic Oath its authority.

In the American medical tradition, certain social revolutions had to occur before the Oath could become a viable source of historical authority. Medicine as practiced in the West during the 18th century was notoriously unsuccessful and unreliable, and patients were more likely to resort to traditional herbal remedies or domestic medicine rather than seek the advice of a professional physician.6 Medicine was not respected as a legitimate profession, and hospitals were thought of as places where people went to die.7 This changed in the mid to late 18th century when many scientific innovations increased the physician’s ability to treat patients with success and the French Revolution introduced standardized training in modern medical schools. These developments provided physicians with the credibility needed to legitimize their profession. They also gave rise to the new practice of swearing the Hippocratic Oath at medical school commencement ceremonies. This exercise, a symbol of classical medical authority, served to link the newly validated modern medical profession to the 2,000-year-old Greek medical tradition.

The market-driven economy emerging from the mid-18th century British Industrial Revolution helped bridge the gap between science and medicine, but as society became industrialized and populations moved to the cities this threatened to undermine medical authority. Communicable diseases ran rampant due to subsistence living standards in impoverished conditions.8 The medical profession now faced not only new diseases it could not eliminate but also a competitive new market economy that was overturning past codes of professional behavior, straining the former camaraderie shared by medical professionals.9 There was increased incentive for British physicians to maintain their elite social status and become knowledgeable in order to attract more clients and differentiate themselves from the competition.10 This new environment provided physicians with new tools and frameworks: 1) Marie-François-Xavier Bichat shifted diagnosis and therapeutics from patient specificity to disease specificity, 2) René Laennec created the stethoscope, 3) germ theory evolved, forever changing the understanding of disease transmission, 4) Louis Pasteur developed the vaccine, and 5) Joseph Lister invented antisepsis.11

The French Revolution of 1798 further contributed to enhance the authority of the medical profession by redefining what it meant to be a professional, developing modern medical schools, and permanently undermining the earlier social hierarchy. The new French liberalism allowed the medical profession to reinvent itself by shifting the authoritative status of the physician from an inherent historic privilege to a status that needed to be earned. When the French Revolution also abolished the Faculty of Medicine—France’s medical guild—with its restrictive practices, and developed the modern medical school system, the elitist British medical guilds, such as the Royal College of Physicians, was threatened. The French, by requiring a steady supply of competent doctors and nurses for their civilian armies,12 created a new system of medical education. Rather than theoretical, the basis of the new teaching medical education, as observed by Antoine François, Compt de Fourcroy, a prominent chemist and professor at the Jardin du Roi in Paris, was “reading little, seeing and doing much.”13

Known as “Paris Medicine,” this system insisted that hospital experience or clinical training should be an essential part of medical education. Hospitals partnered with universities, providing practical clinical training in conjunction with medical lectures. Paris Medicine also insisted on detailed clinical observations during life, routine autopsies, and using statistics to ascertain the efficacy of treatments.14 Medicine became regulated to ensure a standard of medical competency,15 leading in Europe to professional authority based on superior knowledge and skills rather than elite status.

In 19th century America, however, medicine was given more professional credence than that already provided by 18th century social reforms in Europe. Swearing the Hippocratic Oath was used to grant additional credibility by relating the modern medical profession to the respected ancient Greek medical tradition. This practice reflected the current belief that ancient Athens was the cradle of Western civilization and the source of great cultural achievements.16,17 As a classical remnant of antiquity and with its ancient literary style, the Hippocratic Oath provided the modern medical profession with the authority of tradition. Though originally conceived as a code of conduct, it has been constantly redefined by modern interpretations, illustrating that it functions as more than an ethical code. It is the authority granted from both heritage and writing style that lends credibility to newly minted medical professionals.

The most common misconception regarding the Hippocratic Oath is that it has functioned as a symbol of medical tradition since its creation. The earliest surviving fragment of the Hippocratic Oath originates from Egypt in 300 BC, while “allusions to it on the tombstones of doctors from around the ancient world attest to its prestige and importance.” Only by the 4th century AD, however, is there any evidence of the Hippocratic Oath being sworn as it came to stand for the medical profession.18 The ritual of swearing the Oath is an example of a reinvented tradition; there is no evidence of its continuous use throughout history. There is simply the illusion of an ongoing tradition going back to antiquity. The invention of tradition is especially prevalent “when a rapid transformation of society weakens or destroys the social patterns for which ‘old’ traditions had been designed.”19

The legitimization and defining of the modern medical profession through professional authority thus provided the perfect opportunity for antiquarian scholarship which sought such authority in ideas from the past. The increased American interest in ancient Greece provided an ideal setting for the Hippocratic Oath to be integrated into the commencement ceremonies of modern American medical schools.

Stephen Jacyna notes that since 1800 many communities have manufactured traditions to reshape their relationship to an imagined past in order to address contemporary concerns.20 While the Hippocratic Oath is no longer sworn at all medical school commencement ceremonies, it remains a matchless ethical wireframe for the modern medical professional.

Notes

- Keranen, Lisa. “The Hippocratic Oath as Epideictic Rhetoric: Reanimating Medicine’s Past for Its Future.”

- Journal of Medical Humanities 22.1 (2001): 55-68. 61.

- Nutton, Vivian. Ancient Medicine. London: Routledge, 2004. 60.

- Plato. Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 3, translated by W.R.M. Lamb. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1967 : from Protagoras, lines 311 b-c.

- Hutchins, 1952 pg. ix.

- Hutchins, 1952 pg. xi.

- Furst, Lilian R. Medical Progress and Social Reality: a Reader in Nineteenth-century Medicine and Literature. Albany: State University of New York, 2000. 4.

- Furst, 2000 pg. 17.

- Bynum, W. F. The Western Medical Tradition: 1800 to 2000. New York, NY: Cambridge UP, 2006. 16.

- Bynum, 2006 pg. 18.

- Furst, 2000 pg. 1.

- Furst, 2000 pg. 16.

- Bynum, 2006 pg. 41: Especially after Jean Larrey introduces the ambulance volante system by which a service of doctors and nurses provided medical attention near to the battlefront.

- Bynum, 2006 pg. 41.

- Bynum, 2006 pg. 20.

- Bynum, 2006 pg. 16. This marks the rise of empiricism, or the faith in the primacy of observation, experience, and experimentation, which ousts the old schematic, abstract system of a style of medicine sometimes called “library medicine” because of its pronounced theoretical orientation.

- Malamud, Margaret. Ancient Rome and Modern America. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.124-128.

- For further evidence that the United States drew from Ancient Greece, take a moment to examine the classical architecture that abounds in our nation’s capital.

- Nutton, 2004 pg. 68.

- Hobsbawm, E.J., and T.O. Ranger. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]: Cambridge UP, 1983.4.

Appendix: The Hippocratic Oath

I swear by Apollo the physician, by Aesculapius, Health, and All-heal, and all the gods and goddesses, that, according to my ability and judgment, I will keep this Oath and this stipulation – to reckon him who taught me this Art equally dear to me as my parents, to share my substance with him, and relieve his necessities if required; to look upon his offspring in the same footing as my own brothers, and to teach them this art, if they wish to learn it, without fee or stipulation; and that by precept, lecture, and every other mode of instruction, I will impart a knowledge of the Art to my own sons, and those of my teachers, and to disciples bound by a stipulation and oath according to the law of medicine, but to none others. I will follow that system of regiment which, according to ability and judgment, I consider for the benefit of my patients, and abstain from whatever is deleterious and mischievous. I will give no deadly medicine to any one if asked, nor suggest any such counsel; and in like manner I will not give to a woman a pessary to produce abortion. With purity and with holiness I will pass my life and practice my art. I will not cut persons laboring under stone, but will leave this to be done by men who are practitioners of this work. Into whatever houses I enter, I will go into them for the benefit of the sick, and will abstain from every voluntary act of mischief and corruption; and further from the seduction of females or males, of freemen or slaves. Whatever, in connection with my professional practice or not, in connection with it, I see or hear, in the life of men, which ought not to be spoken of abroad, I will not divulge, as reckoning that all such should be kept secret. While I continue to keep this Oath unviolated, may it be granted to me to enjoy life and the practice of the art, respected by all men, in all times! But should I trespass and violate this Oath, may the reverse be my lot!

CHLOÉ M. DELISLE graduated with honors from Macalester College in 2012 with a major in classical civilizations and a minor in biology. Looking forward to a career in medicine, she is currently volunteering at the biomedical foundation, Centro Internacional de Entrenamiento e Investigaciones Médicas (CIDEIM), in Cali, Colombia. There she is working with the Bacterial Resistance laboratory to compare antibiotic stewardship programs and nosocomial surveillance across a network of 25 Colombian hospitals. She is also working on fluency in her third language, Spanish. She is thankful to her oldest sister, Dominique M. DeLisle, for helping her edit this essay.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Winter 2014 – Volume 6, Issue 1

Leave a Reply