Mary Shannon

Portland, Oregon, United States

|

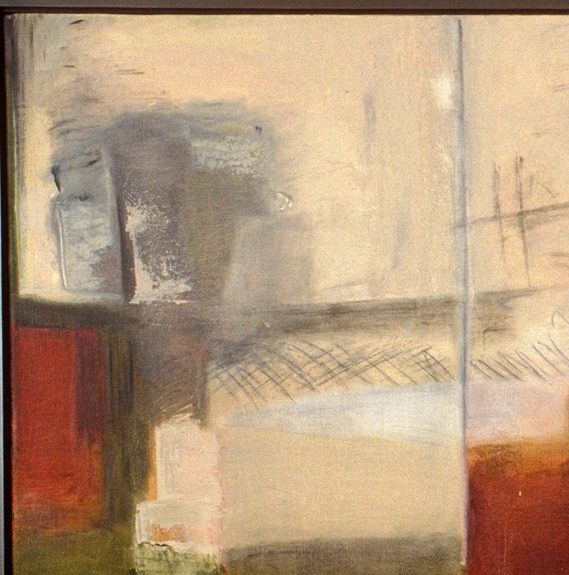

| The mirror of madness Mary T. Shannon Mixed media 5” x 7” |

She was sitting in the dark with one leg hiked up on her bed, staring out the window, the street light angled across her face like a three-quarter moon. I sat cross-legged in the bed next to her trying my best not to yawn—I knew better than to look uninterested or get distracted.

“Can you keep a secret?” Mom asked between drags off her Pall Mall. I nodded solemnly and listened as she whispered warnings about Grandpa poisoning the food, which is why I hadn’t been allowed to eat that day. The week before, she told me Grandpa had gassed the house to try and kill us all, opening every single window in the dead of winter until frost collected on the Venetian blinds and my teeth banged together like piano keys. Grandma said it was “nerves,” that Mom just needed to go back to the state mental hospital where she could get some rest, but Mom said it was living with Grandma and Grandpa that drove her crazy, that living with them was enough to make anyone nuts.

The following morning two men in starched, white shirts and navy suits came to take Mom away again, only this time she didn’t put up a fight—just grabbed a carton of Pall Malls from the top of the ice box and walked out the door. I stood on the front porch and watched as they put her in the backseat of their long, black ship of a car. Even though her face was in a shadow, her expression was unmistakable. It was the same proud, defiant look I had seen on her a thousand times before, the one that marked who she was more than anything else about her. She’d made her life with that look, made it the hard way. It was the only way she knew how.

The next morning I woke up to Grandma and Grandpa talking in the kitchen, their muffled voices bleeding through the walls like secrets. I tiptoed downstairs in the pink, flannel pajamas that I had gotten for my seventh birthday and stood up against the dining room wall to listen.

“Paranoid schizophrenia, that’s what it’s called,” Grandma told Grandpa over breakfast. “There’s no cure for it, but they’re giving her what they call shock treatments, and Dr. Sorensen says those should help. And he’s going to try some different medication this time around too.”

“Well it doesn’t matter what they call it or how many pills they give her, the bottom line is she’s nuttier than a fruit cake,” Grandpa spit. “What they ought to do is lock her up and throw away the key!”

“But maybe things will be different this time around,” Grandma said softly. “Maybe those shock treatments will work and maybe the new medicine will too. Lord knows that’s what I’ve been praying for.”

“Pray all ya want woman, but that won’t change the fact that she’s just plain crazy. Always has been and always will be.”

|

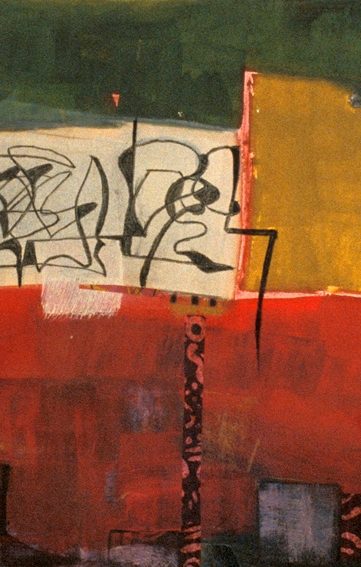

| You can’t see schizophrenia Mary T. Shannon Oil on canvas 24” x 32” |

A chair screeched across the linoleum, and I quickly tiptoed back up to my room, glancing over at Mom’s bed as I lay on my own. The dirty, white sheet she had refused to wash was still wadded up in the middle where she had left it, and her blanket was stuffed at the foot like always. I clasped my hands behind my head and stared up at the cracks in the ceiling, trailing the deepest one all the way down the length of the wall until it almost met the crack in the middle of Mom’s dresser mirror. I mouthed the words to myself: par-a-noid-schiz-o-phre-nia.Paranoid schizophrenia. It sounded serious. I followed the crack back up to the ceiling again, thinking about the last time they had taken her away—when they put her in the violent ward where I was not allowed to visit. I wondered which ward she was in this time and if there were any windows in it. Maybe she was looking at the sun coming through them like I was right now, or maybe they were giving her one of those shock treatments this morning. What were shock treatments anyway? Did they shock the illness right out of you, like when someone slaps you in the face to shock you back into your senses?

Mom always said that men could get as pissed off as they wanted and no one gave it a second thought, but if a woman got good and mad and God forbid, showed it, they either filled her up with drugs, locked her away in the nuthouse, or both. In 1959 women were expected to be soft-spoken and pretty—all buttoned down and proper, but Mom was anything but proper. Never one to follow convention, she didn’t care in the least that her smart mouth and bad temper got her into trouble more often than not. Mom always blurted out exactly what she was thinking no matter how vile or inappropriate, and maybe that’s all it was, I thought. Maybe speaking her mind with so much rage all the time was what made her seem crazy, made her look like she had gone nuts. A lifetime of angry hurt could do that to a person. It could close up your heart so much that all you are left with is a wild, lonely rage that is easily mistaken for crazy, but is not crazy at all—just a closed-up heart crying out for help the only way it knows how.

“Mary!” Grandma called from downstairs. “You’d better get up and get going or you’re going to be late for school.”

“Okay,” I yelled back. “I’m coming!”

I quickly got dressed and ran downstairs; I was almost out the door when Grandma called from the kitchen, “Hold on a minute!”

I stopped short to wait for her in the hallway, and the closer she got the more I could smell a mix of Vicks VapoRub, Doublemint gum, and Clorox bleach—a bittersweet scent I had come to love.

“Now listen,” she said as she wiped her hands off on a dish towel before throwing it over her shoulder. “Your mother is at Longview because they can help her there, but I don’t want you going around telling anyone about this at school, you hear? No sense in airing your dirty laundry.”

|

| The voices in my head Mary T. Shannon Mixed media 36” x 24” |

I nodded up at her, though I already knew better than to tell. I knew it the same way I knew not to tell about our being on welfare or about Mom hearing voices that no one else ever heard. Besides, I was convinced that going crazy was the worst possible thing that could happen to a person—even worse than death. People were afraid of death, but, truth be told, they were afraid of going crazy even more. Death was not embarrassing like being crazy was. No, death was just sad, with lots of sympathy and food for those left behind. There wasn’t anything left behind for the family of a crazy person, except shame.

Three months later, Mom walked in the door carrying a brown, paper bag full of pills that jingled like spare change in her hand. I was sitting at the dining room table eating a peanut butter and jelly sandwich I had made, and when I looked up at her she stared right through me. Her face was a blank and her eyes held nothing—not boredom, not happiness, not even sadness, and she barely blinked. After setting her pills on top of the ice box, she sat down at the table and reached into her dress pocket for a pack of cigarettes, pulling it out slowly and methodically, as if out of habit more than desire. She used to smoke fast and furious. Now she smoked so slowly that by the time she was ready to take another drag the only thing left between her fingers was a long stick of ash.

I looked up at all the pills sitting on top of the ice box, each bottle marked with a different name: thorazine, stelazine, and a host of other names I could not even pronounce. They were lined up in a row like watchful guards sent to calm her nerves and curb her rages, and yet all they had done was steal the life right out of her. There must have been over a dozen of them sitting up there, some old and some new, some of the pills in brown, plastic bottles and some in rust-colored ones. Looking up at all those bottles now, I was convinced that she had been right about the doctors all along—they had finally shut her up, just like she said they would.

Mom never did learn how to be different enough to be found interesting, but not so different that it didn’t scare everybody. Unlike most, she refused to keep her stubborn pride and raging temper under lock and key, so Longview State Mental Hospital went ahead and did it for her. Sometimes I would watch her staring at nothing and wonder if the world inside her head was better than ours—if maybe it was the kind of world that offered love and acceptance no matter if you were crazy or not. I wondered if her world had any color in it, any flowers or grass, or if it was as blank as the look on her face when she was there. Mom never talked about the times she drifted off, and I was too afraid to ask. But whenever I watched her staring off into space I would wonder if she went to that world in the first place because this one never wanted that much to do with her anyway—a world that never did take too kindly to a poor, single mother on welfare—especially one who wasn’t pretty, wasn’t sociable, and wasn’t afraid to show how angry she was about it all.

All through the long, winter months and the wet spring, I kept expecting Mom to change back to her old self again, but the only thing that changed was the world around her. The snow finally melted and the days were getting longer. Daffodils and crocuses shot up in bright, bold sprays of color while Mom stayed transfixed—locked away in a world of her own that no one could touch, not even her. I began to wonder if she would ever snap out of it.

School was almost out for the summer when Mom started coming back to life again, as if the warm weather had poured some energy back into her. I noticed it first in her eyes. Instead of the same empty stare they seemed more focused, as if they were finally seeing what was in front of them. She was smoking her Pall Malls faster too, and she was not sleeping as much. She spent her days sitting at the dining room table smoking and drinking coffee, swirling her baby finger in small, quick circles on the table as if she was tracing something over and over again. Her foot rocked back and forth so hard her whole body moved in time with it.

“You haven’t stopped taking your medication again, have you?” Grandma asked her one morning over breakfast. Mom shot me a quick glance and winked. I could tell by the way she was grinning that she was working hard not to laugh, but then her face turned serious.

“Well what if I have? What business is it of yours anyway? You’re just trying to shut me up like those doctors. I swear, you’re all in cahoots if you ask me!”

I gulped down the rest of my orange juice and started out the door for school. Things were back to normal again.

MARY T. SHANNON, MSW, MS is a psychotherapist, award-winning artist, and author of the memoir, The Sunday Wishbone. A graduate of Columbia University’s program in narrative medicine, Mary specializes in using the transformative power of story and art with clinicians and clients alike. Visit www.marytshannon.com for a complete list of services.

Artist’s statement: Growing up in my mother’s world of paranoid schizophrenia, we lived in a parallel universe of voices, electroshock therapy, and too many pills to count. After the birth of my son, I began using art as a way of healing, and I now incorporate narrative into my work as well. These mixed media pieces were part of a series depicting the many faces of mental illness and reflect the pain and anguish of a mind gone awry.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Fall 2011 – Volume 3, Issue 3

Fall 2011 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply